Revolution of the Psyche, by Krishnamurti

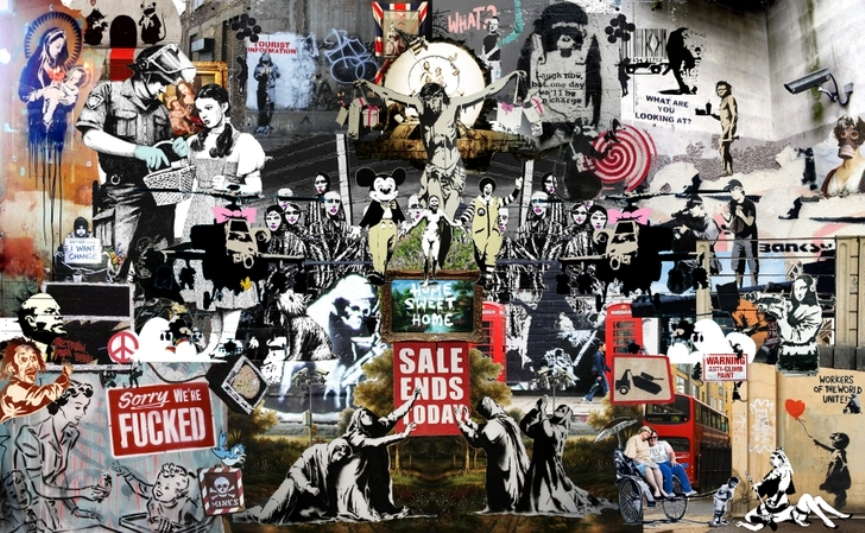

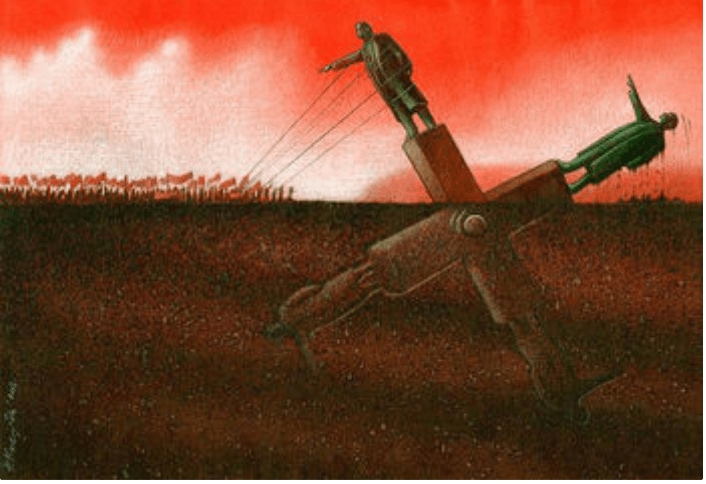

The Thinker and the Thought: “What you are, the world is. So your problem is the world’s problem”

Introduction

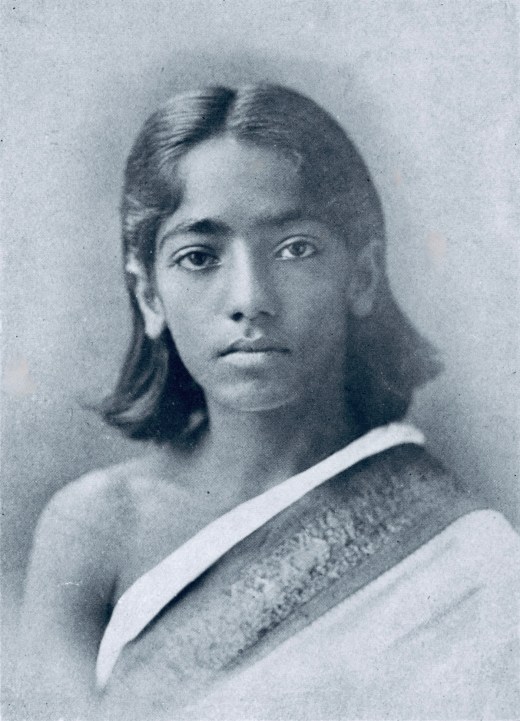

Krishnamurti in 1910. The year before, theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater, who claimed clairvoyance, had noticed Krishnamurti on the Society’s beach on the Adyar river and was amazed by the “most wonderful aura he had ever seen, without a particle of selfishness in it.” Leadbeater was convinced that the boy would become a spiritual teacher and a great orator; the likely “vehicle for the Lord Maitreya” in theosophical doctrine, an advanced spiritual entity periodically appearing on Earth as a World Teacher to guide the evolution of humankind. Krishnamurti later rejected this role, and indeed rejected the whole idea of following “roles”, after an intense spiritual experience in 1922.

Jiddu Krishnamurti was an Indian philosopher, speaker, and writer. In his early life, he was groomed to be the new ‘World Teacher’ (the Theosophical concept of Maitreya), but he later rejected this mantle and withdrew from the Theosophy organization behind it.

His interests included psychological revolution, the nature of mind, meditation, holistic inquiry, human relationships, and bringing about radical change in society. He stressed the need for a revolution in the psyche of every human being and emphasised that such revolution cannot be brought about by any external authority, be it religious, political, or social.

Krishnamurti was often seen as a spiritual master, although he interestingly mistrusted all religions and denounced the Eastern convention of deifying living spiritual masters. This gives some of his thinking an unusual and indeed at times devastating honesty. Perhaps nowhere is this more seen than in his critiques of the ego – the basis of both the modern personality and of most orthodox psychoanalytic thinking (the purpose of much Freudian and Jungian analysis is actually to strengthen the ego). The goal in Krishnamurti’s vision seems to be to go beyond both ‘self’ and beyond ‘mind’ (which, like Tolle, Krishnamurti equates with ego or what Blake calls “Selfhood”). “Judgement and comparison commit us irrevocably to duality”, he says – and we can never be happy therefore while we are in this state. And neither can those around us.

Why should we study killing? One might just as readily ask, Why study sex? The two questions have much in common. Every society has a blind spot, an area into which it has great difficulty looking. Today that blind spot is killing. A century ago it was sex.

Why should we study killing? One might just as readily ask, Why study sex? The two questions have much in common. Every society has a blind spot, an area into which it has great difficulty looking. Today that blind spot is killing. A century ago it was sex.