Going Beyond Good & Evil: Restoring Eden in the Brain

Introduction: Blake’s Laocoön and the serpents of Morality

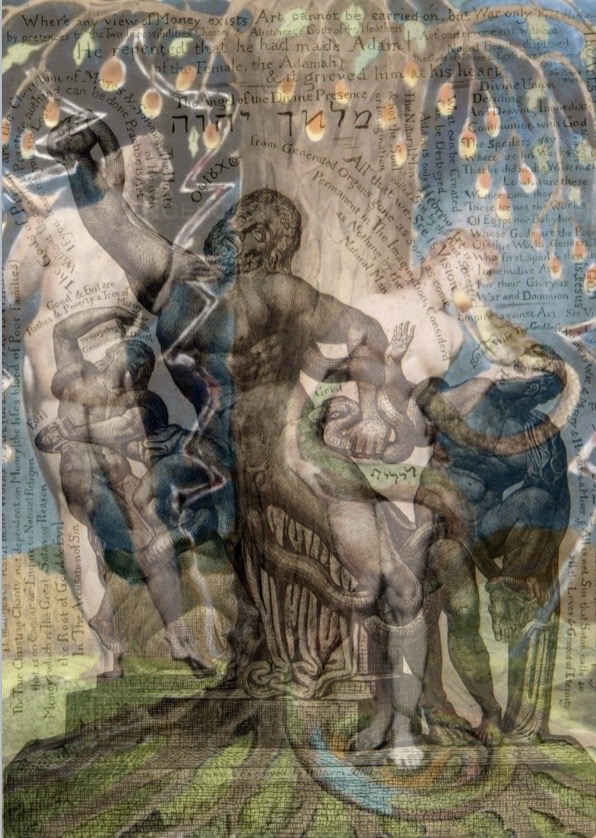

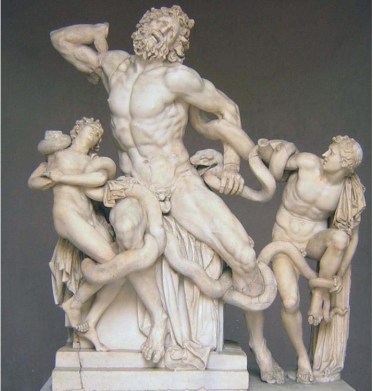

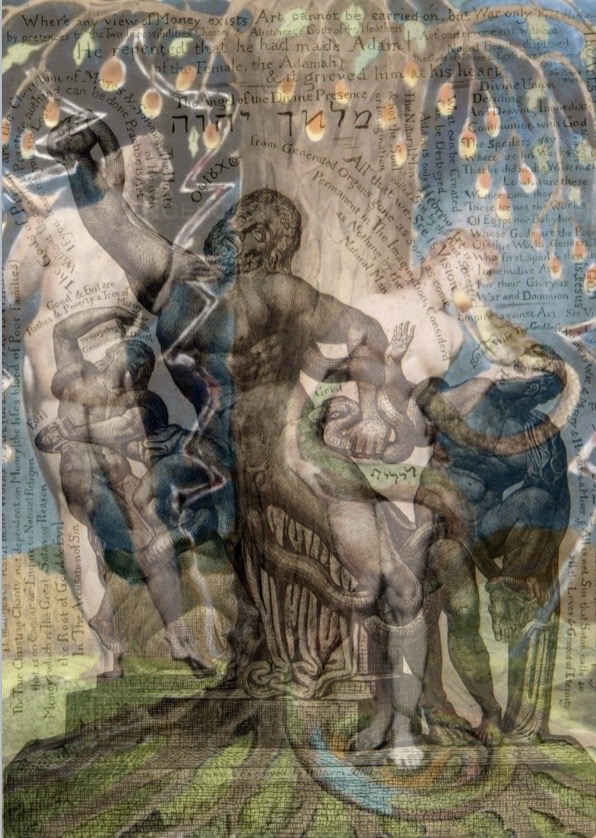

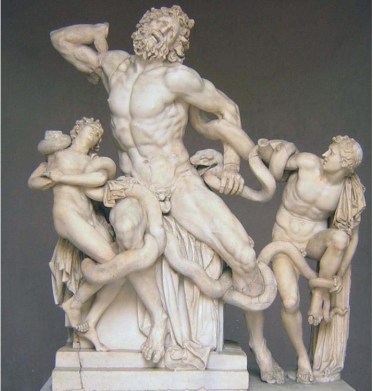

The original Laocoön. In Blake’s reading, the serpents overcoming the priest represent the twin Powers or programs of “Good” and “Evil”, which eventually suffocate him, and his vision of God.

The question, and questioning, of morality, is central to one of Blake’s most iconic and futuristic images, the Laocoön. Even though Blake’s best-known works often combine image and text in a single plate, the Laocoön stands apart as the only one to be centered around a faithful copy of a piece of antique sculpture, a fact which attests to its hold on his imagination.

Another arresting feature of the plate is the atypical density of its textual matter, composed in at least two distinct scripts and three different languages, and the seemingly arbitrary, discontinuous manner of its arrangement on the page. Julia Wright observes, “the design recalls a jigsaw puzzle more than a page from an emblem book, graffiti more than an engraving, and marginal annotations more than aphorisms on art” .

It resembles no other work by Blake, and he left no instructions on how his wide-ranging statements should be organized, or in what order they should be read. Without an obvious starting point, one could try a conventional approach, beginning with the first line of horizontal text at the top of the page: “Where any view of Money exists Art cannot be carried on but War only”; but then one could just as well start at the bottom, with the caption identifying the three figures as “הי & his two sons Satan & Adam.” Either way, the reader is sure not to get far before having to stop and decide where to begin again; and from there one choice seems as good as another.

Read More