Logic and Mysticism: William Blake, Bertrand Russell, and Allen Ginsberg

The Way to Truth: The Lamb or the Tyger?

The Ancient of Days over Bikini Atoll, where America exploded a massive hydrogen bomb in 1954. It was a thousand times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. On witnessing the first detonation of a nuclear weapon on July 16, 1945, a piece of Hindu scripture ran through the mind of scientist Robert Oppenheimer: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”

Introduction: Blake and Bertrand Russell

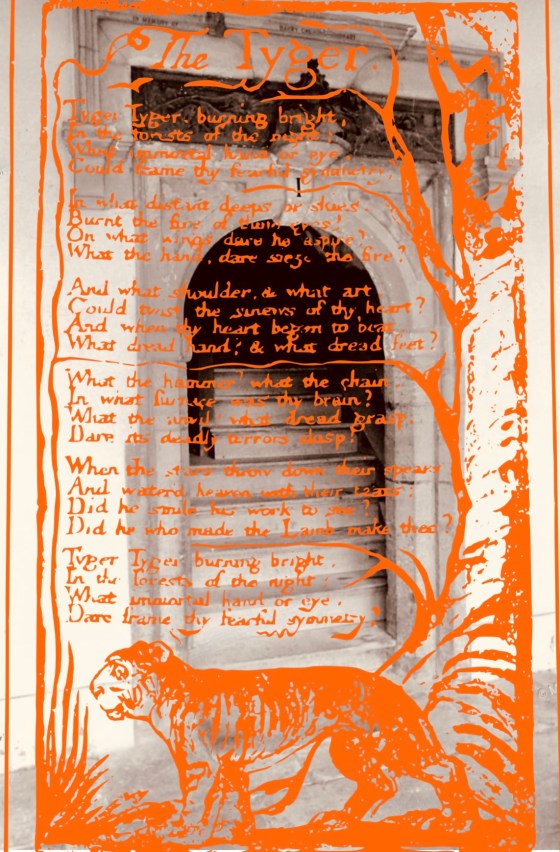

Entrance to the rooms Russell occupied as a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge University, where he first heard the sound of Blake’s Tyger.

In the first volume of his autobiography, Nobel Prize laureate Bertrand Russell recalled being stopped dead in his tracks while trying to descend a staircase in Trinity College Cambridge by his friend Crompton reciting Blake’s poem The Tyger. He wrote:

One of my earliest memories of Crompton is of meeting him in the darkest part of a winding College staircase and his suddenly quoting, without any previous word, the whole of “Tyger, Tyger, burning bright.” I had never, till that moment, heard of Blake, and the poem affected me so much that I came dizzy and had to lean against the wall.

The encounter with Blake’s Tyger seems to have made a lasting impression on the mathematician and philosopher. Russell returned to him again in his 1918 essay Mysticism and Logic, where he suggested that the search for truth could be reached both through hard science and pure speculation. In the essay Russell contrasts two “great men,” Enlightenment philosopher David Hume, whose “scientific impulse reigns quite unchecked,” and poet William Blake, in whom “a strong hostility to science co-exists with profound mystic insight.” It’s interesting that Russell chooses Blake for an example.