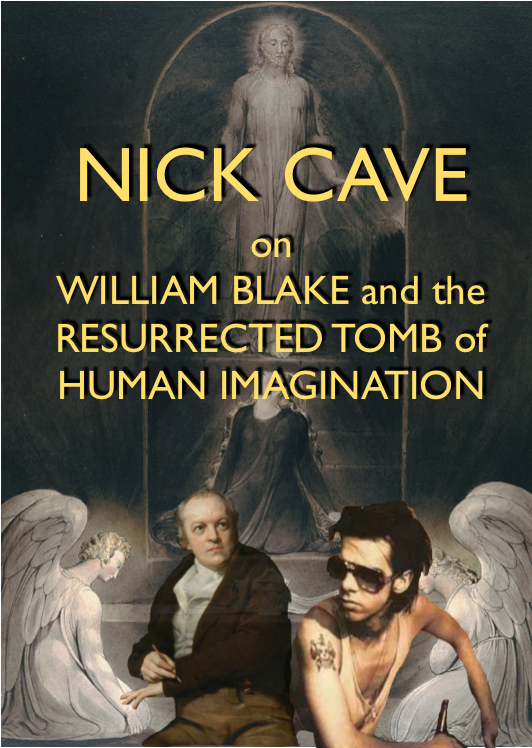

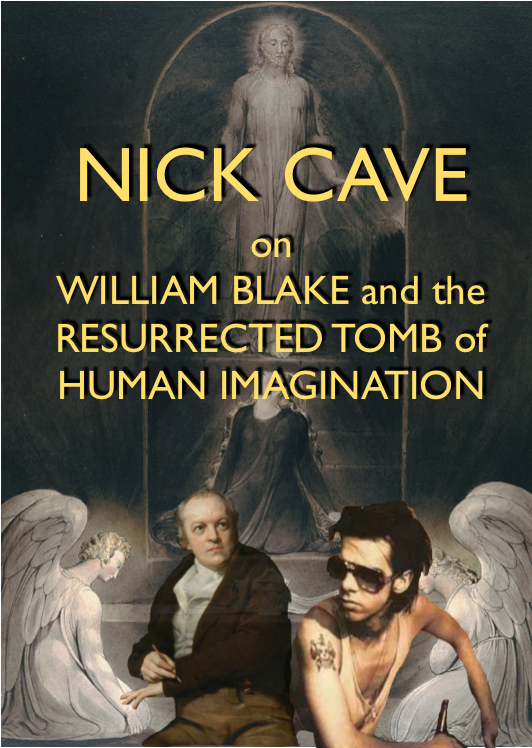

Nick Cave on William Blake: Where does Creativity come from?

The Australian musician and songwriter Nick Cave, responding on his website ‘The Red Hand Files‘ to the question ‘How do you know when you have written something worthwhile? What is your process?’, remarks that Blake’s insights into the nature of Imagination and the imaginative process were key to him in this:

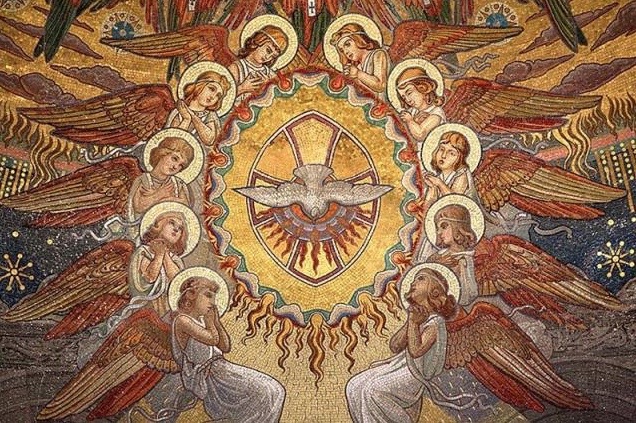

In Issue #87 I wrote about my favourite line from the New Testament: ‘Mary Magdalene and the other Mary remained standing there in front of the tomb.’ To me, this line seems to sum up, among other things, the process of songwriting. William Blake said ‘Jesus is the imagination’ and these words have always resonated with me. They have bound together the notion of Jesus and the creative act, and lifted it into the supernatural sphere.

The moment of the cave.

This is a surely a fascinating observation, and connection. Why particularly that line from the Bible, that stood out for him so much, amid so many other striking lines? What was it about the image of the tomb, or the sense of both the possibility of emptiness and of emergence, the moment of waiting or expectation, that so resonated with him? Was it some sort of analogy between the resurrected tomb and the cave of creativity, of ‘Imagination’? Thankfully, Cave himself provided some further illumination:

A large part of the process of songwriting is spent waiting in a state of attention before the unknown. We stand in vigil, waiting for Jesus to emerge from the tomb — the divine idea, the beautiful idea — and reveal Himself.

Cave’s sense that there is something ‘transcendent’ about our creative moments and experiences is very striking, and very unexpected in our commercialised, cynical, post-modern age. And also unexpected in an artist not writing from any orthodox religious perspective (“I’m not religious, and I’m not a Christian,” he once remarked, “but I do reserve the right to believe in the possibility of a god.”) Cave is aware that there is something profoundly strange about creativity, something mysterious (or “supernatural” as he puts it) about the process by which songs, and images, and poetry, emerge out of, apparently, thin air. Cave suggests that Blake is right to connect them not to material or mundane processes in this world but to something altogether deeper and more mysterious.

Read More

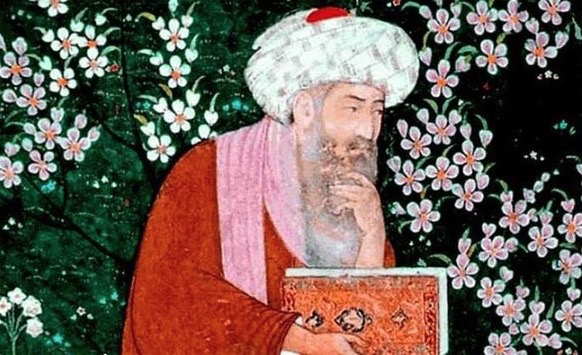

According to Professor Henry Corbin, one of the 20th century’s most prolific scholars of Islamic mysticism, Ibn ‘Arabî (1165–1240) was “a spiritual genius who was not only one of the greatest masters of Sufism in Islam, but also one of the great mystics of all time.”

According to Professor Henry Corbin, one of the 20th century’s most prolific scholars of Islamic mysticism, Ibn ‘Arabî (1165–1240) was “a spiritual genius who was not only one of the greatest masters of Sufism in Islam, but also one of the great mystics of all time.”