Yeats on Blake: William Blake and the Human Imagination

Ideas of Good and Evil, by W. B. Yeats

Introduction: Future Tense

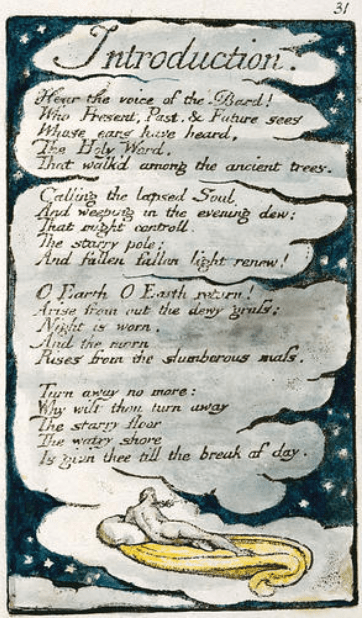

“Hear the voice of the Bard! Who Present, Past, & Future sees”. This sense of the poet as participating in a non-temporal or multi-temporal domain was also recognised by Shelley, who notes in A Defence of Poetry that “A poet participates in the eternal, the infinite, and the one; as far as relates to his conceptions, time and place and number are not.” It is for this reason, he adds, that poets are also prophets: those who can see into the present.

There have been men who loved the future like a mistress, and the future mixed her breath into their breath and shook her hair about them, and hid them from the understanding of their times. William Blake was one of these men, and if he spoke confusedly and obscurely it was because he spoke things for whose speaking he could find no models in the world about him.

He announced the religion of art, of which no man dreamed in the world about him; and he understood it more perfectly than the thousands of subtle spirits who have received its baptism in the world about us, because, in the beginning of important things – in the beginning of love, in the beginning of the day, in the beginning of any work, there is a moment when we understand more perfectly than we understand again until all is finished.

In his time educated people believed that they amused themselves with books of imagination but that they “made their souls” by listening to sermons and by doing or by not doing certain things. When they had to explain why serious people like themselves honoured the great poets greatly they were hard put to it for lack of good reasons.

In our time we are agreed that we “make our souls” out of some one of the great poets of ancient times, or out of Shelley or Wordsworth, or Goethe or Balzac, or Flaubert, or Count Tolstoy, in the books he wrote before he became a prophet and fell into a lesser order, or out of Mr. Whistler’s pictures, while we amuse ourselves, or, at best, make a poorer sort of soul, by listening to sermons or by doing or by not doing certain things.