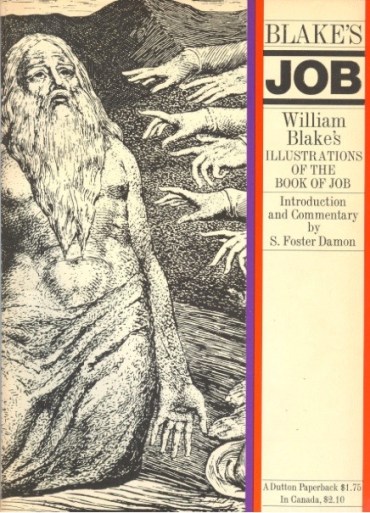

Tradition and Imagination in William Blake’s Illustrations for the Book of Job

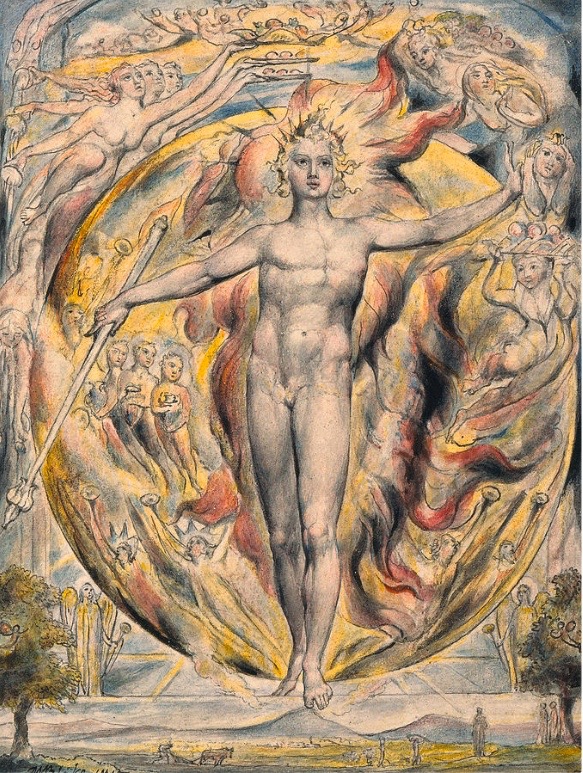

Suffering into Wisdom: If Oedipus was the key figure for the 20th Century then Job is the archetypal figure for the 21st century, embodying the awakening into the social and the imaginative nature of self, through the collapse of ego and the experience of trauma and suffering

Introduction

“Previous studies have concentrated on the engraved set, and no one has explored the implications of the earlier dating now agreed for the watercolour series.”

Blake created two versions of his Illustrations of the Book of Job, and it is now agreed that about twenty years separates his first watercolour series and the final engraved set of plates. The first (‘Butts’) series of water-colours was the product of the tumultuous and creative years 1805-10, following a time when Blake experienced a strong sense of vision and Christian regeneration; whereas the engraved set was produced 1821-1826, at the end of his life.

This article explores Blake’s treatment of the Job theme, in which the ‘friends-turned-accusers’ seem to have been a central pre-occupation. Blake’s illustrations contain important elements which are not found in the Old Testament text, and I consider Blake’s imaginative use of this material, exploring in particular the importance to Blake of St.Teresa, Fenelon, Mme. Guyon, Hervey and other people of ‘prayer’.

Blake’s Job was unique in the corpus of his work. Previous studies have followed Wicksteed in concentrating on the engraved set, and no one has explored the implications of the earlier dating now agreed for the watercolour series. The thesis is essentially concerned with Blake’s Christocentric theme, and Job’s inner journey of prayer, in these illustrations.

Read More