The Eye Altering: William Blake and the Nature of Observation, by Naomi Billingsley

The Jesus Field: Observation, Participation, and how Images alter the Observer

![]()

Introduction: Jesus and the Human Imagination

In All Religions are One (1788) Blake declared “That the Poetic Genius is the true Man. and that the body or outward form of Man is derived from the Poetic Genius” (Principle 1st). Blake here is drawing attention to the great, hidden secret of both reality and the nature of God, which is Form. Forms are not ‘things’ but processes or organising movements. Forms are rooted in and expressions of (creations of) an underlying “former”, which in Blake’s early work he called the “Poetic Genius” to signify its formative aspect, a term which is derived from the same root as the word from which we also get “genesis” and indeed “genetic”. According to Blake it is this that gives each body its individual as well as generic “form”. In contrast to almost all other spiritual traditions, Blake understood that forms are not temporary and unimportant but eternal, continually creating and recreating themselves. They are vast invisible forming fields, similar to what Rupert Sheldrake has more recently termed “morphogenetic fields”.

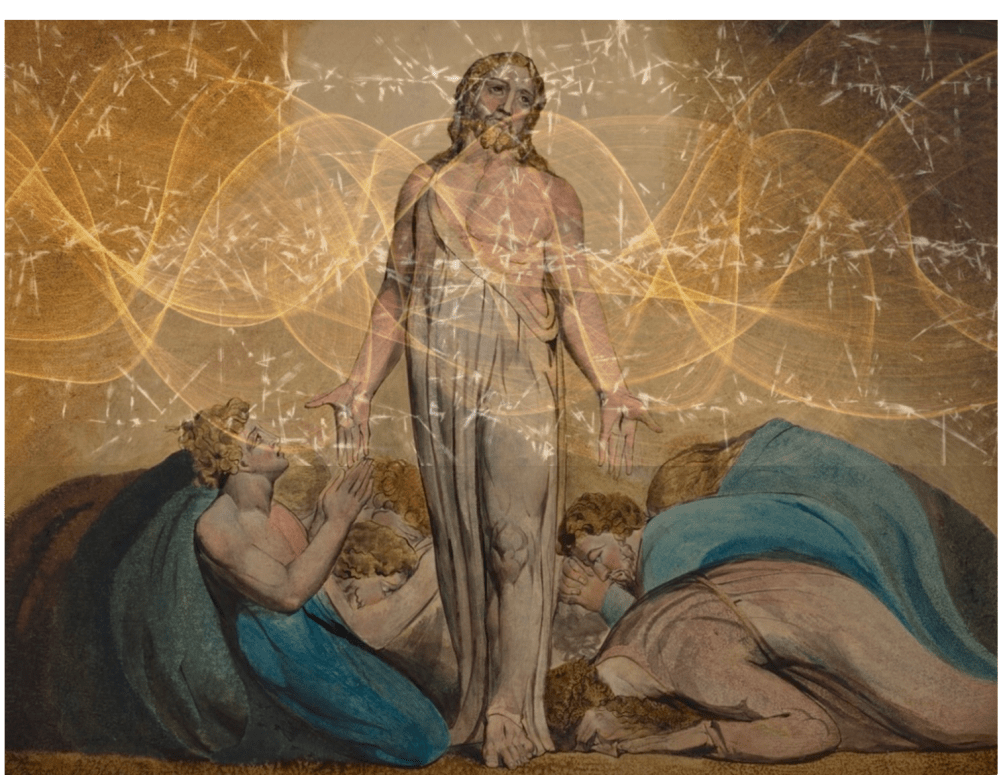

William Blake believed that Christianity is art and that Jesus Christ was an artist, who is both the model and the source of artistic activity. These ideas are central to his artistic and religious vision, and are expressed in various forms throughout his career: from the early account of the Poetic Genius in All Religions are One, to the late aphorisms of the Laocoön plate.

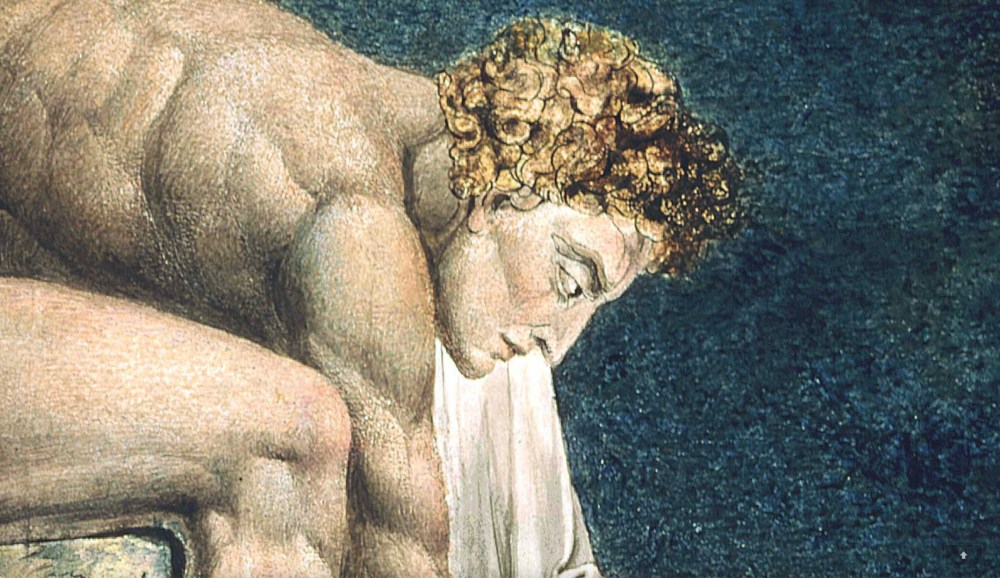

This article examines why Blake identified Christ as artist and Christianity as art. My central argument is that Blake expresses this theory – or theology – of art through his visual representations of Christ. Blake did not mean that Jesus produced works of fine art, nor that one must do so in order to be Christian; rather, Christ’s identity is Imagination, and as such all his acts and all activity in him are art. Thus, I examine Blake’s depictions of Jesus’ life and ministry, and show that Blake represents these themes as analogous to the work of the artist because Jesus changes the way that we perceive the world.

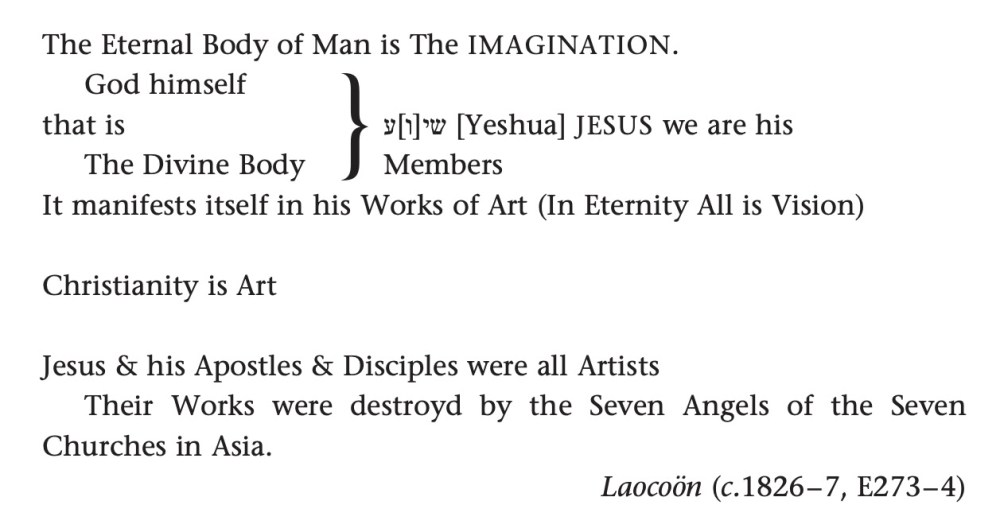

As Morris Eaves highlights at the end of Blake’s Theory of Art, for Blake, Jesus’ art was his public ministry – his parables and miracles were acts of self-expression, which sought to create a new social order. So too Blake seeks, through his art, to engender a community of Imagination. This community is the Divine Body, which is Jesus, who is Imagination – as expressed in the Laocoön aphorism quoted below:

Thus, Blake’s depictions of Christ are also representations of artistic activity; they include not only images of Jesus’ public ministry, but also of his birth, death and resurrection, as an apocalyptic agent, and in extra-biblical roles.

Whilst Blake’s vision of Christ as the supreme type of the artist was by no means a static concept, it emerged in his works as early as All Religions are One and can be found in works from throughout his career. This article explores how Blake envisaged the life of Christ as manifesting the principles of art through case studies that examine five major themes in Blake’s depictions of Christ in key pictorial projects in his oeuvre: art as regeneration, art as inspiration, art as facilitator, art as eternal, and art as iconoclastic. Imagination alters the way we see the world, and our relationship with it: that is to say, since observed and observed are fundamentally entwined and interdependent (or “entangled”, in the language of modern quantum field theory), imagination alters, or restores, the nature of reality itself – to a unified and integrated (“holistic”) whole, or “vision”.