William Blake

Team Human: Beyond the Machine, by Douglas Rushkoff

I Must Create My Own Operating System or Be Enslaved by Another’s

One of the most exciting, thought-provoking, inspiring, and Blakean thinkers of his generation, Douglas Rushkoff leads the way in developing a revolutionary 21st century project of recentering what it means to be human. His compelling and innovative take on everything from psychedelic drugs and the post-capitalist economy to the nature of digital technology and how to hack into our cultural programmes and start rewriting them, makes him a leading figure in understanding the dynamic intersection of technology, society and culture. He’s a media theorist – he’s the guy who coined the terms ‘viral media’, ‘digital native’ and ‘social currency’ – as well as an innovative writer, lecturer and hyper-cool graphic novelist, perhaps best known for his association with the early cyberpunk culture, and his advocacy of open source solutions to social problems.

Here’s just a glimpse of the magic.

“Team Human is most simply a sustained argument for human intervention in the Machine, that we’re living increasingly automated, directed, digital, capitalist lives – we’re living in a world that does not promote or celebrate human autonomy.”

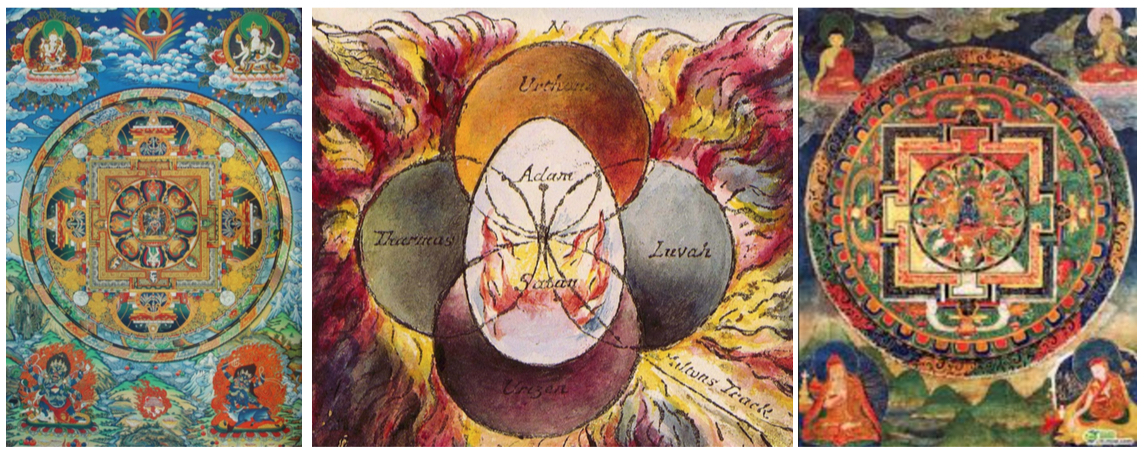

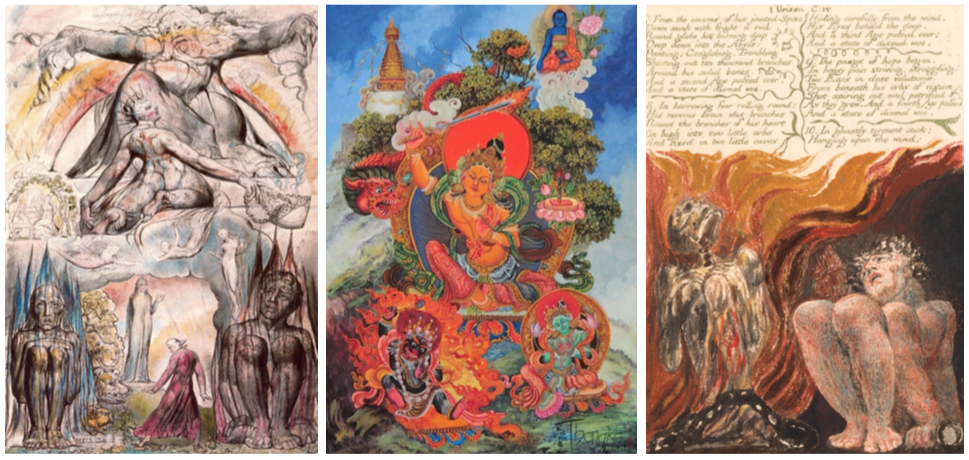

Awakenings: Blake and the Buddha, by Mark S. Ferrara

Ch’an Buddhism and the Prophetic Poems of William Blake

The similarities between William Blake’s philosophical system and that of Buddhism (particularly the Ch’an(a) or Zen School) are no less than astonishing. One is struck by a fundamental similitude underlying the teaching of the Ch’an school and that of Blake’s radical epistemology.

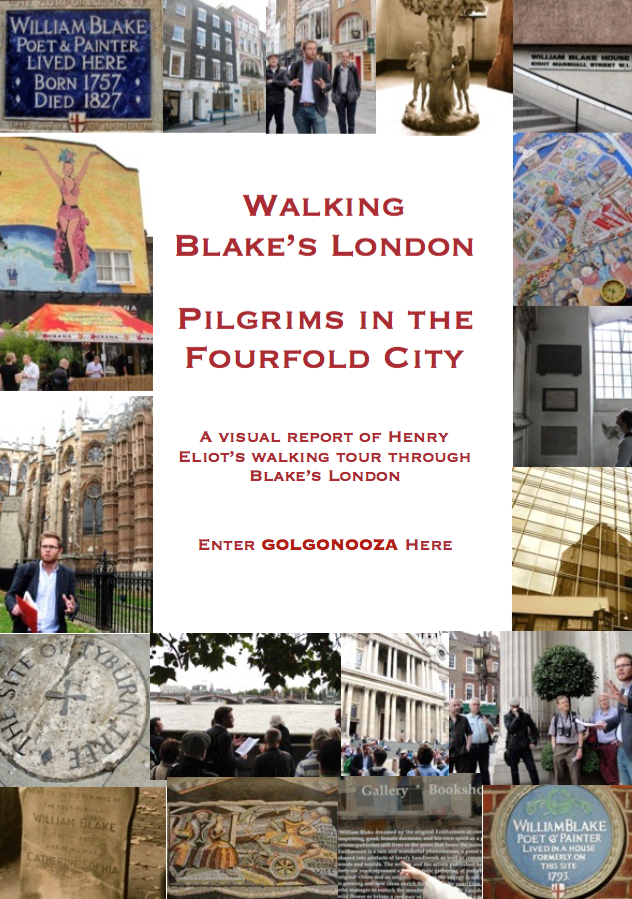

Laocoön, by William Blake

Where any view of Money exists, Art cannot be carried on, but War only

Blake’s extraordinary piece of graffiti art, 200 years before Jean-Michel Basquiat or Banksy. The words themselves seem part of the serpentine struggle, as if logos itself was implicated in the fall into division

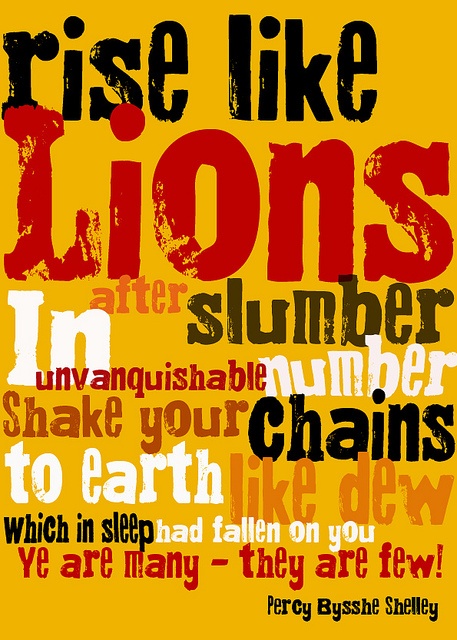

Masks of Anarchy, by Paul Foot

Rise like lions after slumber: Revolutionary Shelley

“Poetry is our most fundamental weapon against alienation, isolation, automation, apathy and despair” – Demson, Masks of Anarchy

Richard Holmes rightly describes Shelley’s The Mask of Anarchy as “the greatest political poem ever written in English”. The ninety-two verses of The Mask were written in hot indignation in September 1819, immediately after Shelley heard the news of the massacre at Peterloo. It is the most concise, the most popularly written and the most explicit statement of his political ideas in poetry.

Eternity in an Hour: Blake in Time, by S. Foster Damon

Left Brain Time and Right Brain Space

Eternity is what always is, the reality underlying all temporal phenomena, the nunc stans of St. Thomas Aquinas. It is vulgarly supposed to be an endless prolongation of Time, to begin in the future; it is instead the annihilation of Time, which is limited to this temporal world; in short, Eternity is the real Now.

The problem of conceptualising eternity with the linear time (left hemisphere) program. We don’t enter Eternity – we enter Time; we’re already in Eternity

“Eternity Exists, and All Things in Eternity” (Vision of the Last Judgment). Whatever was, is, and shall be is there. “Every thing exists & not one sigh nor smile nor tear, one hair nor particle of dust, not one can pass away” (Jerusalem). Nothing real can have a literal beginning. Man “pre-existed” before his creation in Eden, which was only his materialising, an episode of his Fall.

Through a Glass Darkly: Cleansing the Doors of Religion, by Christopher Rowland

Seeing the Bible through Blake’s Eyes

A decade ago I was invited by one of my graduate students to share in a complete reading of William Blake’s Jerusalem. A group of 12 of us attended the event, among them Philip Pullman, a Blake admirer. Each member of the group was asked to share in turn their experience of Blake and his work.

Reading Blake’s Jerusalem: (left to right) Tim Heath (the Spectre), Philip Pullman (Albion), and Val Doulton (the Daughters of Albion)

I found myself blurting out the words, ‘Blake has taught me to read the Bible.’ I had never articulated it like that before, but since then I have often recollected that off-the-cuff comment. I had never thought in that way before. I have reflected on the truth of that statement and come to see that Blake (as in much else in my intellectual endeavour) has been an important catalyst for my thoughts and understanding (Rowland, Blake and the Bible).

In trying to articulate what it is that Blake has taught me, I have started with this because the words ‘Blake taught me’ suggest a direct impact rather than a detached engagement with someone’s words. There’s always a sense when engaging with any of Blake’s works that more is going on than a mere encounter with words or images. It is what is constitutive of what is ‘more’ that is one of the most important aspects of Blake’s works, indeed, is the way he relates to pedagogy.

‘The Human Form Divine’: Radicalism and Orthodoxy in William Blake, by Rowan Williams

The Human Imagination and the Eternal Body

Priests promoting Conflict and Soldiers promoting Peace

To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

All pray in their distress;

And to these virtues of delight

Return their thankfulness.

For Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is God, our father dear,

And Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is Man, his child and care.

For Mercy has a human heart,

Pity a human face,

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.

Then every man, of every clime,

That prays in his distress,

Prays to the human form divine,

Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace.

And all must love the human form,

In heathen, Turk, or Jew;

Where Mercy, Love, and Pity dwell

There God is dwelling too.

Blake might have been surprised to learn that these verses, ‘The Divine Image’, from Songs of Innocence, are sometimes printed – and sung – as a hymn. On their own, they are indeed a touchingly direct statement of a certain kind of Christian humanism, apparently optimistic and universalist – a suitable text for the enlightened, perhaps rather Tolystoyan, Christian who looks to Blake as part of his or her canon.

But Blake is a dialectical writer, to a rare and vertiginous degree, and to understand what a text like this means we also have to read his own reply to it – indeed, his own critique of it. The textual history of this dialogue is itself intriguing, as if he could not easily settle on how he was to ‘voice’ the necessary riposte. His first attempt, not finally included in the Songs of Experience, survives in a design from 1791 or 1792:

Blake’s Christ-Consciousness, by Kathleen Raine

BLAKE is only known to have attended a religious service three times in his life: he was baptized, in the year 1757, at the beautiful font of St. James’s, Piccadilly. He was married in Battersea Old Church; and at his own wish, his burial service (he died in 1827) was according to the rites of the Church of England. His admiration for such dissenters as John Wesley and William Law notwithstanding, he preferred the national Church to non-conformity; perhaps in part because of his love for those Gothic churches—and especially Westminster Abbey—in whose architecture he saw the true expression of the spirit, in contrast with Wren’s St. Paul’s, which he saw as a monument to Deism and human reason. His last great work was the splendid but incomplete series of illustrations to Dante; he admired St. Teresa of Avila, and the French Quietists, Fénélon and Mme Guyon, no less than the Protestant mystics, of whom two in particular—Jakob Boehme and Emmanuel Swedenborg—were his acknowledged masters.

Blake contrasted the “Living Form” of Gothic (infinite, organic) with the cold rationalism of Wren’s “monument to Deism”: round, rational, and religious

He declared himself a Christian without reservation: “I still and shall to Eternity Embrace Christianity and Adore him who is the Express image of God” he declared. He never had any period of doubt, early or late. But what kind of Christian was our great visionary and national prophet?

Review of 2016

A New Year, A New Self, A New Politics

Thank you to everyone who’s followed the posts this year, left comments, suggested ideas, and supported thehumandivine project in its first year. Over the last twelve months we’ve posted a new blog each week, covering everything from Kabbalah and Brexit to neuroscience and the sexuality of God – all united by an approach rooted in William Blake’s imaginative and radical take on God. We hope this will be a useful resource for anyone wanting to explore Blake’s alternative vision and its relevance for today.

But in 2017 thehumandivine is changing! From January the site is going to develop in new and exciting ways: instead of weekly articles there’ll be more in-depth monthly posts exploring key passages from the Bible (Book of Job, Ezekiel, etc) from a radical Blakean perspective, to help illuminate them and also to suggest their relevance to what’s happening today, and how these narratives and thought systems continue to shape both our inner and outer lives.

But in 2017 thehumandivine is changing! From January the site is going to develop in new and exciting ways: instead of weekly articles there’ll be more in-depth monthly posts exploring key passages from the Bible (Book of Job, Ezekiel, etc) from a radical Blakean perspective, to help illuminate them and also to suggest their relevance to what’s happening today, and how these narratives and thought systems continue to shape both our inner and outer lives.

Blake read the Bible not as “the word of God” to be followed literally but as a profound record of the psychological evolution of humanity – its terrifying psychic splits and dissections, its self-alienation and state of “exile”, its fall into “division”, its capacity for forgiveness, and its longing for integration and wholeness.

We’re also hoping to develop the themes of the website in practical ways: there are plans to organise a conference next summer to explore the implications of Blake for contemporary theology and to see if the Church can be shifted more in a Blakean direction. The theme of the conference will be Blake’s observation: “The Vision of Christ that thou dost see Is my Vision’s Greatest Enemy” – and what he means by this. Watch this space!

Here’s a selection of some of the highlights from 2016:

NICK CAVE: The Flesh Made Word: A Poetic Interpretation

NICK CAVE: The Flesh Made Word: A Poetic Interpretation

ROD TWEEDY: William Blake, Brexit and the Re-Awakening of Albion

ROD TWEEDY: William Blake, Brexit and the Re-Awakening of Albion

IAIN McGILCHRIST: William Blake and the Divided Brain

IAIN McGILCHRIST: William Blake and the Divided Brain

SHAMS TABRIZI: The 40 Rules of Love

SHAMS TABRIZI: The 40 Rules of Love

PETER ANDERSON: Poetry & Madness: Blake, Eigen & the Psychotic God

PETER ANDERSON: Poetry & Madness: Blake, Eigen & the Psychotic God

CHRISTOPHER Z. HOBSON: Anarchism and William Blake’s Idea of Jesus

CHRISTOPHER Z. HOBSON: Anarchism and William Blake’s Idea of Jesus

ERIC PYLE: Blake’s Illustrations of Dante’s Hell

ERIC PYLE: Blake’s Illustrations of Dante’s Hell

E.M. NOTENBOOM: From Hell: Alan Moore and William Blake

E.M. NOTENBOOM: From Hell: Alan Moore and William Blake

ANDREI BURKE: The Secret World and Sexual Rebellion of William Blake

ANDREI BURKE: The Secret World and Sexual Rebellion of William Blake

SUSANNE M. SKLAR: Blake’s Jerusalem as Visionary Theatre

SUSANNE M. SKLAR: Blake’s Jerusalem as Visionary Theatre

Happy Christmas!!