Rise like lions after slumber: Revolutionary Shelley

“Poetry is our most fundamental weapon against alienation, isolation, automation, apathy and despair” – Demson, Masks of Anarchy

Richard Holmes rightly describes Shelley’s The Mask of Anarchy as “the greatest political poem ever written in English”. The ninety-two verses of The Mask were written in hot indignation in September 1819, immediately after Shelley heard the news of the massacre at Peterloo. It is the most concise, the most popularly written and the most explicit statement of his political ideas in poetry.

It stars with a devastating attack on the Tory ministry. Shelley imagines, as if in a dream, the three English despots, Castlereagh, Eldon and Sidmouth, gliding past him in masks, disguised as Murder, Fraud and Hypocrisy. Castlereagh is feeding seven bloodhounds with human hearts. These are Britain’s seven allies, whom Castlereagh appeased at the Congress of Vienna after Waterloo by agreeing not to press for the abolition of slavery.

It stars with a devastating attack on the Tory ministry. Shelley imagines, as if in a dream, the three English despots, Castlereagh, Eldon and Sidmouth, gliding past him in masks, disguised as Murder, Fraud and Hypocrisy. Castlereagh is feeding seven bloodhounds with human hearts. These are Britain’s seven allies, whom Castlereagh appeased at the Congress of Vienna after Waterloo by agreeing not to press for the abolition of slavery.

As I lay asleep in Italy

There came a voice from over the Sea,

And with great power it forth led me

To walk in the visions of Poesy.

I met Murder on the way–

He had a mask like Castlereagh–

Very smooth he looked, yet grim;

Seven blood-hounds followed him:

All were fat; and well they might

Be in admirable plight,

For one by one, and two by two,

He tossed them human hearts to chewWhich from his wide cloak he drew.

Next came Fraud, and he had on,

Like Eldon, an ermined gown;

His big tears, for he wept well,

Turned to mill-stones as they fell.

And the little children, who

Round his feet played to and fro,

Thinking every tear a gem,

Had their brains knocked out by them.

Clothed with the Bible, as with light,

And the shadows of the night,

Like Sidmouth, next, Hypocrisy

On a crocodile rode by.

And many more Destructions played

In this ghastly masquerade,

All disguised, even to the eyes,

Like Bishops, lawyers, peers, or spies.

‘I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW’ Shelley called his poem ‘The Mask of Anarchy’ to point to the brutal and chaotic nature of the system, which was concealed under a rubric of law and order, monarchy, and militarism – indeed, violence (as illustrated by this 1819 cartoon of the Peterloo massacre by Cruikshank) is essential to maintaining the pretence of order. In the poem, Shelley brilliantly rhymes ‘anarchy’ with ‘monarchy’ to reveal this underlying connection. The word ‘anarchy’ is popularly used by the authorities to generate fear amongst the people, and this is how Shelley is using the term here – to suggest that this chaos is already implicit within the system. He himself was a believer in the other, liberational, sense of the word – ‘philosophical anarchism’, in the tradition of Godwin and Paine, though he took those ideas much further

At the back of the procession, leading his regiment from behind, is Anarchy, who represents “GOD, AND KING AND LAW”.

Last came Anarchy: he rode

On a white horse, splashed with blood;

He was pale even to the lips,

Like Death in the Apocalypse.

And he wore a kingly crown;

And in his grasp a sceptre shone;

On his brow this mark I saw –

‘I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW!’

The idea of ‘waking up’ is central to Shelley’s poem, as indicated in its opening lines and in the figure who rises up

A “mighty troop around”, who take their orders from Anarchy, ride through England tearing everything to pieces and terrifying the people. They are met on the outskirts of London by a host of army officers, lawyers and priests, who fling themselves down in obeisance, muttering:

‘Our purses are empty, our swords are cold,

Give us glory, and blood, and gold.’

Anarchy “bowed and grinned” to them all, and sends his spies to launch a provocative assault on the Bank of England and the Tower of London (as Sidmouth’s spies had provoked a handful of conspirators in 1816).

And was proceeding with intent

To meet his pensioned Parliament.

The forces of God and King and Law represented by this grotesque parade seem omnipotent. They drown with their clamour every syllable of generosity or peace. But suddenly, just at the moment of their highest triumph, there rushes into their path “a maniac maid”:

The forces of God and King and Law represented by this grotesque parade seem omnipotent. They drown with their clamour every syllable of generosity or peace. But suddenly, just at the moment of their highest triumph, there rushes into their path “a maniac maid”:

And her name was Hope, she said:

But she looked more like Despair

The maid is at her wits’ end. She yells out that her Father, Time, had watched all his children die in gloom and poverty, and was himself driven mad with disease and despair. She is the only child left. There is nothing for it but the most desperate direct action.

‘My father Time is weak and gray

With waiting for a better day;

See how idiot-like he stands,

Fumbling with his palsied hands!

‘He has had child after child,

And the dust of death is piled

Over every one but me –

Misery, oh, Misery!’

Then she lay down in the street,

Right before the horses’ feet,

Expecting, with a patient eye,

Murder, Fraud, and Anarchy.

But she is not run down. For suddenly in between her and the advancing horde, “A mist, a light, an image rose.” It is “small at first”, but then “it grew” into a great shape in armour, with luminous wings and a helmet which glistens like the sun. The image cannot really be seen by human beings, but they know it is there. It is the spirit of awakened humanity, mingled with the spirit of direct action. And it has the most astonishing effect:

But she is not run down. For suddenly in between her and the advancing horde, “A mist, a light, an image rose.” It is “small at first”, but then “it grew” into a great shape in armour, with luminous wings and a helmet which glistens like the sun. The image cannot really be seen by human beings, but they know it is there. It is the spirit of awakened humanity, mingled with the spirit of direct action. And it has the most astonishing effect:

As flowers beneath May’s footstep waken,

As stars from Night’s loose hair are shaken,

As waves arise when loud winds call,

Thoughts sprung where’er that step did fall.

“Thoughts sprung.” People start to think about their condition, and the way out of it. Nothing, in Shelley’s view, is more powerful.

And the prostrate multitude

Looked – and ankle-deep in blood,

Hope, that maiden most serene,

Was walking with a quiet mien:

Before this, Hope was a “maniac maid”, who looked more like despair. But now she becomes confident and serene.

And Anarchy, the ghastly birth,

Lay dead earth upon the earth;

The Horse of Death tameless as wind

Fled, and with his hoofs did grind

To dust the murderers thronged behind.

“Why is it visionary – have you tried?” Shelley wrote The Mask of Anarchy in 1819 following the Peterloo Massacre of that year. In his call for freedom, it is perhaps the first modern statement of the principle of nonviolent resistance.

If Shelley and been a mere dreamer, the poem might have ended there. The death of all that is horrible on earth, he might have concluded, can be put to flight by mists and images, or by abstract concepts such as Hope. But the poem does not end there. It is only a third of the way through. The bulk of the poem is a speech. Who makes the speech is not quite clear, though the speaker is certainly female.

The words, the poem tells us, “arose” as if the very earth had uttered them in an “accent unwithstood”, forced out by the blood of English people that had fallen on it. But its message, in contrast to the imagery which has given birth to it, is practical. There are no more images – just plain, blunt language which any working man or woman could understand.

The speech has three sections, directed to the three questions all agitators must ask and answer. What is wrong? What would you put in its place? And what are you going to do to replace the former with the latter?

What is wrong? Or, as the speech puts it, what is slavery? That is easily answered. Slavery, she replies, is exploitation. It is the consequence of one set of men having command over the labour of others, without any responsibility to them.

So that ye for them are made,

Loom, and plough, and sword, and spade ;

With or without your own will, bent

To their defence and nourishment.

“Exploitation brings poverty and homelessness”

Exploitation brings poverty and homelessness:

Tis to see your children weak

With their mothers pine and peak,

When the winter winds are bleak:-

They are dying whilst I speak.

Exploitation means robbed labour, far more valuable than anything stolen from the poor in the “tyrannies of old”. But above all, it means the crushing of the human spirit in the interests of a few purses:

‘Tis to be a slave in soul,

And to hold no strong controul

Over your own wills, but be

All that others make of ye.

“the crushing of the human spirit in the interests of a few purses”

What would you put in its place? Freedom, of course. And what is freedom? It is bread and clothes and warmth. It is “a check” on the rich. It is a system of law which favours no one above another and “shields alike the high and low”. It is peace. It based on “science, poetry and thought”:

“Thou art clothes, and fire, and food

For the trampled multitude :

No — in countries that are free

Such starvation cannot be,

As in England now we see.

“To the rich thou art a check,

When his foot is on the neck

Of his victim; thou dost make

That he treads upon a snake.

Spirit, Patience, Gentleness,

All that can adorn and bless,

Art thou -“

But stop! Shelley stops himself in mid-verse, for he knows that as soon as an agitator gets carried away with verbal descriptions of his ideal, he will lose his audience and his key to success. The verse goes on:

But stop! Shelley stops himself in mid-verse, for he knows that as soon as an agitator gets carried away with verbal descriptions of his ideal, he will lose his audience and his key to success. The verse goes on:

“Let deeds, not words, express

Thine exceeding loveliness.”

The last twenty-six verses of the poem are about these “deeds, not words”. They begin with a call for a demonstration:

“Let a great assembly be

Of the fearless, of the free”

“Let a great assembly be Of the fearless, of the free”

Who would come to this demonstration?

“From the workhouse and the prison,

Where pale as corpses newly risen,

Women, children, young, and old,

Groan for pain, and weep for cold -“

Mingled with these people who have “common wants and common cares” are a few “from the palaces” who feel compassion for the exploited.

Inevitably, the poem continues, such a demonstration would provoke a reaction. The yeomanry would fall upon it firing their guns, flashing their bayonets and scything at the crowd with their scimitars. What should the crowd do then? In his advice to the demonstrators, incitement to revenge is replace by something rather different:

Inevitably, the poem continues, such a demonstration would provoke a reaction. The yeomanry would fall upon it firing their guns, flashing their bayonets and scything at the crowd with their scimitars. What should the crowd do then? In his advice to the demonstrators, incitement to revenge is replace by something rather different:

“Stand ye calm and resolute,

Like a forest close and mute …”

When the yeomanry charge,

And if then the tyrants dare,

Let them ride among you there ;

Slash, and stab, and maim, and hew ;

What they like, that let them do.

With folded arms and steady eyes,

And little fear and less surprise,

Look upon them as they stay

Till their rage has died away.

Such a tactic, Shelley suggests, would conquer the yeomanry. They would be shamed out of further repression. Women would point them out, and ridicule them. Acquaintances in the street would embarrass them by reminding them that they were among the monsters who had attacked an innocent crowd.

A demonstrator, Ieshia Evans, protesting the shooting death of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, 2016. The idea of nonviolent resistance is to allow the system to reveal its true nature – for the law enforcers and police to therefore realise their role in the brutal maintenance of anarchy. Shame is currently used as a form of social control: Shelley advocates using this weapon back on the shamers

More practically, Shelley suggests, the passive resistance of the masses would split the yeomanry from the soldiers.

“And the bold, true warriors,

Who have hugged Danger in wars,

Will turn to those who would be free

Ashamed of such base company.”

“the bold, true warriors, Who have hugged Danger in wars, Will turn to those who would be free” Veterans for Peace UK mark Remembrance Sunday at the London Cenotaph. They carry a banner that reads ‘NEVER AGAIN’

There was some prospect of this. The soldiers at Peterloo had not joined in the slaughter. One or two senior officers had even intervened with the yeomanry to try to stop the charges. “For shame, gentlemen,” one army officer had yelled at the magistrates, “What are you about? The people cannot get away.” The soldiers, what is more, did not have the same quarrel with the masses as did the yeomanry. They were continuously bullied by the same sort of people as those who charged down the meeting at St Peter’s Fields. Many soldiers were tired of discipline and susceptible to agitation. The splitting of the soldiers from the class who gave them orders was possible and potentially explosive.

This has since become an aim of revolutionaries all over the world, but at that time it was almost unheard of. That Shelley should have tried to engineer such a split shows how sharp was his tactical sense of action. He was not just for the idea of protest. He applied himself rigorously to the details of protest in a action.

“And these words shall then become

Like Oppression’s thundered doom,

Ringing through each heart and brain,

Heard again — again — again.

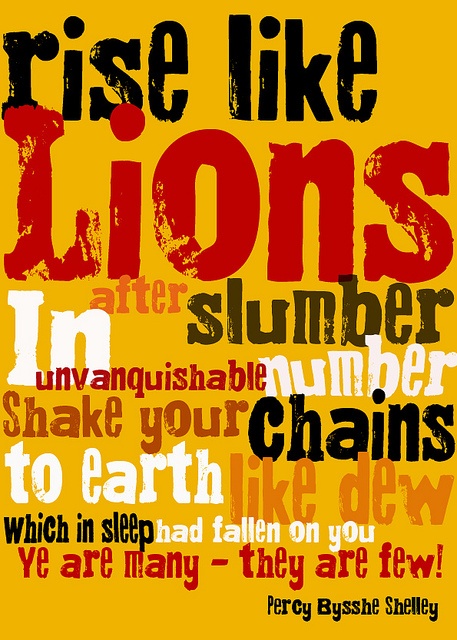

Rise like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number !

Shake your chains to earth, like dew

Which in sleep had fall’n on you :

Ye are many — they are few.”

For all the caution of his practical proposals, Shelley’s chief anxiety was that the masses were apathetic, and that their apathy was the government’s central prop. That was why the people had to rise like lions.

Shelley’s Influence

That closing verse is perhaps one of the best known pieces of poetry in any movement of the oppressed all over the world. The Chartists knew it in the 19th century and so did the striking women garment workers in 1909 New York. It was chanted on demonstrations in Tiananmen Square (1989) and Tahrir Square (2011). The last lines were adapted to ‘We Are Many’ by the campaign against the Poll Tax. The proposed film about the February 2003 Stop the War demo against the Iraq war is titled ‘We are the Many’.

That closing verse is perhaps one of the best known pieces of poetry in any movement of the oppressed all over the world. The Chartists knew it in the 19th century and so did the striking women garment workers in 1909 New York. It was chanted on demonstrations in Tiananmen Square (1989) and Tahrir Square (2011). The last lines were adapted to ‘We Are Many’ by the campaign against the Poll Tax. The proposed film about the February 2003 Stop the War demo against the Iraq war is titled ‘We are the Many’.

The Chartists, Robert Owen, Engels, Marx and many others all were to a greater or lesser extent, inspired by Shelley’s ideas. The influence of Shelley’s doctrine of massive, non-violent protest on Ghandi is also well documented.

In May 2017, Jeremy Corbyn wound up his election campaign with an electrifying speech during which he name-checked Shelley and quoted the concluding lines of Mask of Anarchy. The entire audience joined him for the last few words and rose in a standing ovation that was amazingly sustained. The significance of Shelley’s role here is not to be underestimated. A major election was just fought, and arguably won, on principles outlined 200 years ago by Shelley. By a radical poet.

Author, educator, and activist Howard Zinn also refers to the poem in A People’s History of the United States. In a subsequent interview, he underscored the power of the poem, suggesting: “What a remarkable affirmation of the power of people who seem to have no power. Ye are many, they are few. It has always seemed to me that poetry, music, literature, contribute very special power.” In particular, Zinn uses The Mask of Anarchy as an example of literature that members of the American labour movement would read to other workers to inform and educate them.

Engels earlier remarked that “Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of his readers in the proletariat; the bourgeoisie own the castrated editions – the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today.” While Marx acutely observed that “The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand and love them rejoice that Byron died at 36. Because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at 29 because he was essentially a revolutionist and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism.”

“Shelley was everything Lord Byron played at being”

Michael Demson, in his amazing graphic novel Masks of Anarchy, traces the influence of Shelley’s great poem to the founding of one of the greatest labour unions in the history of America, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union.

This blog is an edited version of Paul Foot’s section on The Mask of Anarchy in Red Shelley. Sections are also taken from Jacqueline Mulhallen’s excellent piece ‘Rise like lions after slumber: Revolutionary Shelley‘ in Counterfire, and Graham Henderson’s outstanding blog piece for The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘Paul Foot Speaks!! The Revolutionary Percy Bysshe Shelley‘.