Ecstasy and Psychosis: Who We Really Are

In many ways, I believe that Michael Eigen is attempting to restore to psychology a dimension suppressed by the scientistic ambitions of the academicized discipline, where the drastic attempt to reduce language to a vehicle for hard data makes of language itself nothing but an empty shell, good only to serve as a frame for the apparent objectivity of statistics. Where Freud could only grudgingly wonder at poetry as a form of psychological gnosis, Eigen understands that poetry—and, very possibly, therapy, too—has the function of revealing who we are. “Poetry”, he says, “is dusting off the true self”.

Poetry and Madness

But what exactly is ‘the true self’? In The Psychotic Core (2004) the argument outlined in the opening statement hinges on the possibility of “a psychotic kernel in every person”, while in Eigen’s Ecstasy (2001) the opening sentence declares, “Ecstasy is the heart’s center.” The heart, the core. The ecstatic, the psychotic—are these then one and the same?

Is God, too, then, mad? To William Blake, he is. The God of Creation—Urizen (Your Reason/Horizon) in the first of Blake’s Prophetic books—himself precipitates the catastrophe of Creation by splitting away from the state of unity-in-multiplicity characteristic of the Eternals, and willfully plunging through the fires of his dark desire to emerge isolated, if self-aggrandizing, in a void of his own making:

First I fought with the fire, consum’d

Inwards, into a deep world within:

A void immense, wild, dark, & deep,

Where nothing was, Nature’s wide womb,

And self-balanc’d, stretch’d over the void,

I alone, even I!

Poised over his own emptiness, which he sees as external to himself, and objectifies as “Nature’s wide womb,” Urizen is about to impregnate himself and, thus, to ensure that all he brings forth, from the illimitable reaches of the astronomical universe to poor, gender-split humankind, will be as flawed as he is. In the beginning, therefore, is the Fall. Of God, not man.

As above, so below.

Eigen and Blake

In Ecstasy, Eigen the psychoanalytic psalmist gives way to a burst of splendid optimism as he traces, following in the footsteps of Federn and Freud, evidence for an ideal, indeed a god-like ego, in ontogeny:

In Ecstasy, Eigen the psychoanalytic psalmist gives way to a burst of splendid optimism as he traces, following in the footsteps of Federn and Freud, evidence for an ideal, indeed a god-like ego, in ontogeny:

The ego is the id’s first love object, and the ego is its own ideal. What an amazing ego or I. Pumped up from the beginning. No wonder Paul Federn picked up on these Freudian threads and saw the early ego as a cosmic I, boundless. Streams of erotic energy feeding I-feeling, I-feeling feeling ideal. Is everything a comedown after this? The radiant I, pulsating, sun-like, ecstatic in its own existence. Freud tells us that the early I’s boundaries are coextensive with all that is. One = All.

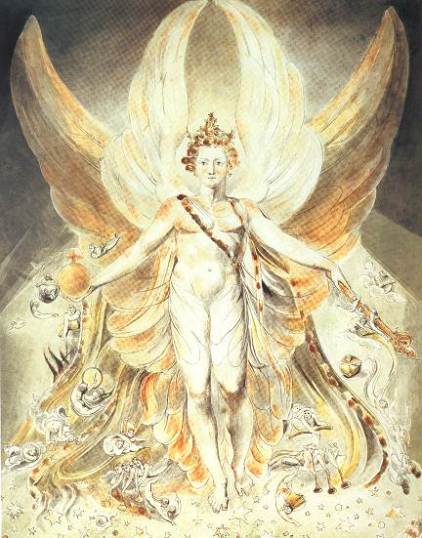

“The radiant I, pulsating, sun-like”: Blake’s depiction of the rational ego, aka ‘Satan in his Original Glory’

But, for Blake, “all that is” is already Urizenic. This does not mean a simple negation: One ≠ All. The point is, rather, that the One is a usurper, displacing the ineffable completeness of being, the confluence with eternity for which it is no substitute.

Everything is a comedown after this.

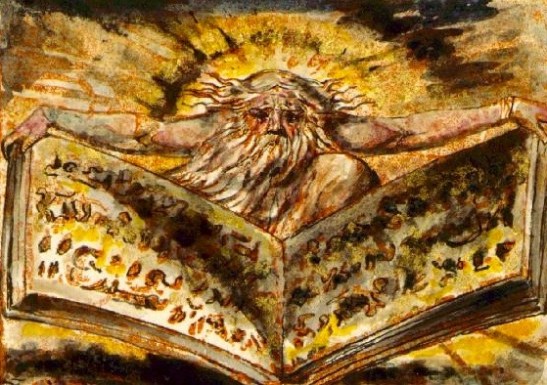

In the Urizenic world, the One is nothing but a mode of consolidation of power. So much is evident when Urizen wields “with strong hand the Book / Of eternal brass” he has written, decreeing

Laws of peace, of love, of unity,

Of pity, compassion, forgiveness.

Let each chuse one habitation,

His ancient infinite mansion.

One command, one joy, one desire,

One curse, one weight, one measure,

One King, one God, one Law.

“One”, here, is pounded in damning repetitiveness. Also, the “Book,” capitalized, can refer only to one book, while its “brass” could imply a brazen act, the act of a tyrant, an upstart, demonstrably bent upon reigning without end. While “Laws of peace, of love, of unity,” and so on, may at a glance seem wonderful, a moment’s reflection reveals them to be oppressive in the extreme. No one can love, pity, or forgive on the basis of heavy-handed authoritarian fiat; besides, there would be no need for any such good, kindly qualities if the world were not inevitably already a site of negativity, suffering, and cruelty.

The Book. “Laws of peace, of love, of unity”: the key word here is “Laws”

It is all in Blake.

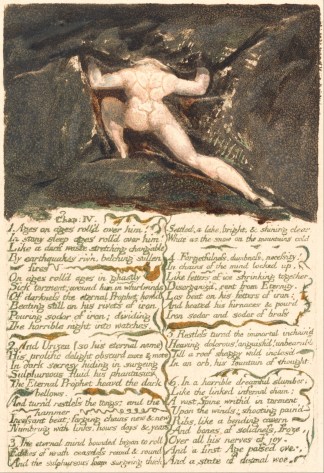

“something that never actually did happen, but that always is happening”: Urizen’s act of abstraction and self-enclosure within the human brain

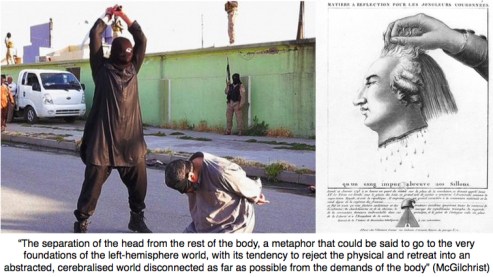

Archetypally identical both with Yahweh and Enlightenment Reason (in fact, his name is derived from the latter), Urizen hurtles on, trapped in the whirlwind of his own (un)doing, the stupendous enormity of his vain attempt upon breaking from the Eternals to create a world in his own image without at the same time wreaking universal death and destruction. The epic of Urizen is mythic—that is to say, a poetic account of something that never actually did happen, but that always is happening. Historically, the case in point is the European Enlightenment.

With its claim that the world can be explained without reference to God, the Enlightenment mythically replicates the schizoid split of the Beginning. Isolating itself in the interests of achieving dominance as the One Truth, Reason broke away, and succeeded in its aim, so that today, not only in the West but increasingly throughout the globe, scientific rationalism rules. Post-Enlightenment Reason, and the bounds formed by a strictly rational–materialist understanding of things, have thus become  “your horizon.” Meanwhile, as “your reason,” the governing power of ego, Urizen arises within us, too.

“your horizon.” Meanwhile, as “your reason,” the governing power of ego, Urizen arises within us, too.

The Eternals said: “What is this? Death.

Urizen is a clod of clay.”

We are all made of the same clay.

Fearful Symmetries

How to reconcile Blake and Eigen?

Where Eigen writes, as he does in Ecstasy, of the “divine-demonic,” Blake, in The First Book of Urizen, writes, we could say, of the “demonic-divine.”

Mirror images.

Mirror images.

But for Blake, Urizen = Yahweh. While for Eigen, Yahweh ≠ Urizen.

Even so, Blake’s Gothic Gnosticism, opposed as it is to Eigen’s psychoanalytic Judaism, might be paralleled with Eigen’s Kabbalistic postmodernism. Perhaps at a point beyond God and before the Beginning—Ain Soph for Eigen, the Eternals for Blake—the two could connect. Or (and this may amount to the same thing) at a  point both here and now, where theological superstructures are not yet an obstacle:

point both here and now, where theological superstructures are not yet an obstacle:

Eigen: I avow that the core of our existence is ecstasy.

Blake: For every thing that lives is Holy.

Blake’s strength of emphasis falls upon “lives”: “For every thing that lives . . .” For Eigen, strength lies in the stance: “I avow . . .” where he iterates his central assertion. Yet both statements are themselves ecstatic.

The holy, said Heidegger, the holy is prior to the gods. And it is the task of poets in a destitute time (our own) to reveal, if not call into being, the holy.

Blake and Eigen: their task.

A Little Blakefest

In Ecstasy, Eigen offers “a little Blakefest” containing, among others, the following:

He who sees the Infinite in all things sees God. He who sees the Ratio only, sees himself only.

Exuberance is Beauty.

Energy is the only life and is from the body and Reason is the bound or outward circumference of Energy.

Energy is Eternal Delight.

Excess of sorrow laughs. Excess of joy weeps.

Joys impregnate. Sorrows bring forth.

If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear as it is: infinite.

Ecstasy is not to be achieved by cutting away from the body in pursuit of ever-higher planes of the intellect, as if it were possible to consummate identity with the godhead only in the realm of absolute purity of thought, as Plotinus once advocated.

The Cutters

In any case, no such neo-Platonic sublime would appear to be operative today, although a parallel practice, relatively mindless as well as inverted, exists among those who perform acts of cutting upon their body—“cutters” Eigen calls them. (Sylvia Plath in The Bell Jar, I remember—or rather, her alter ego, Esther Greenwood—at first feels “nothing,” but then “a small, deep thrill” when she experimentally cuts her lower leg with a razor blade.)

Contra Plotinus, Eigen sees ecstasy as arising primarily in the body, not the mind. Like Plotinus, he believes that ecstasy at its highest issues in “union with God,” but ecstasy for Eigen is always already connected to our living, physical being, indivisible from “the body’s movements, muscles, mucous membranes, flow of breath and blood. In the Bible,” he adds, “Israel is told not to eat the blood of animals because the soul is in the blood. Ecstasy is in the blood.  Blood ecstasies can be terrible”.

Blood ecstasies can be terrible”.

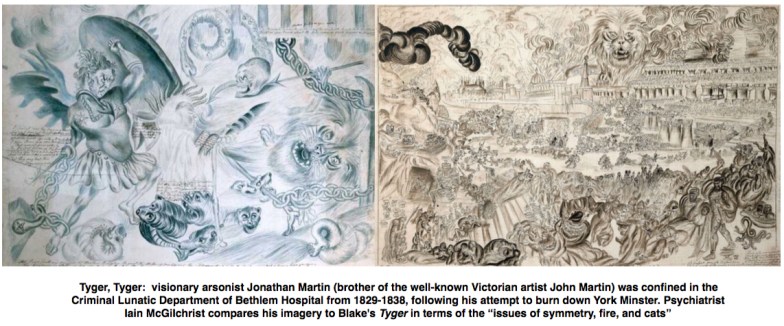

Tyger, tyger, burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

Challenge taken. Yet, we do actually know what “hand or eye” has forged this creature. The tiger is Urizen’s masterpiece.

Is Night also a Sun?

What I do find, time and again, is the word, “light.” In what way, if any, is an evocation of light sufficient to dispel the terrible darkness in which we live?

The Urizenic Enlightenment of Europe has led to the disappearance of the self into nothing but a chain of chemical reactions, an immense field of exploitation for the pharmaceutical industry.

I’d like to ask Eigen:

Why is it that “light” should rhyme with “night”?

Is it simply a coincidence, meaningless? Or does it mean that,

Yes, in the end,

Night is also a sun?

Peter Anderson is an award-winning South African writer. He holds a doctorate from Boston University, and is an associate professor of English at Austin College in North Texas. He is the author of a collection of poems, Vanishing Ground; in addition, his work in fiction and poetry has appeared in numerous literary magazines, and has been anthologized in both the United States and South Africa. Most recently, his novel, The Unspeakable, won the 2015 Literary Fiction Book Review award for Excellence in Literary Fiction and the 2013 Alex la Guma Award for International Fiction. His research interests are in the connections between psychoanalysis, gnosis, and imaginative literature.

This article is an edited excerpt from his chapter ‘Michael Eigen’s Ecstasy as/and poetry’, in Living Moments: On the Work of Michael Eigen, edited by Stephen Bloch and Loray Daws (Karnac Books, 2015), and is reprinted by kind permission of Karnac Books. To receive similar blogs please click on ‘Follow’ [bottom right corner] ➵

One comment