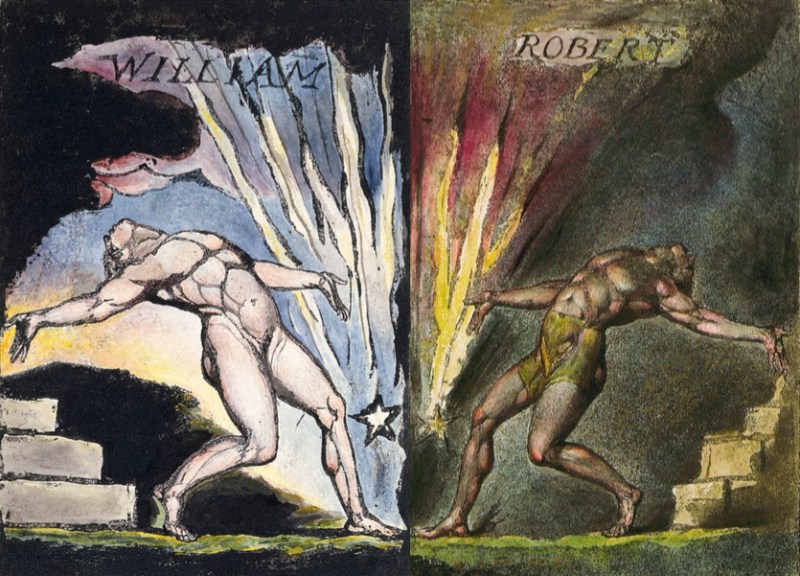

Walking Blake’s London, by Akala and Mr Gee

Hearing the mind-forged manacles

Take a trip around the place that you live. What do you see? What do you feel?

Over 200 years ago, that’s exactly what William Blake did. What happened on that trip – what did he see? what did he feel? – but most importantly, what did it inspire him to write?

He described these “chartered” streets, and even the river Thames as being chartered – he was expressing the sense of ownership, the fact that the streets are owned by someone. Or a river – when you think of a river, you imagine something that flows freely – but he’s pointing to the fact that the river is also owned by someone.

London at that time was starting to assert itself, it was starting to beat its chest. But Blake just peals the veneer behind that image, and speaks about “Weakness” and “Woe”. These are not adjectives that London would use to describe itself to the world.

Watts gained a large following in the San Francisco Bay Area and wrote more than 25 books and articles on subjects important to Eastern and Western religion, including The Way of Zen (1957), one of the first bestselling books on Buddhism, and

Watts gained a large following in the San Francisco Bay Area and wrote more than 25 books and articles on subjects important to Eastern and Western religion, including The Way of Zen (1957), one of the first bestselling books on Buddhism, and