The Great Selfhood Satan: The Pathological Nature of the Human Ego

William Blake, Eckhart Tolle, and the Obstacle to God

“Imagine a chief of police trying to find an arsonist when the arsonist is the chief of police” (Tolle)

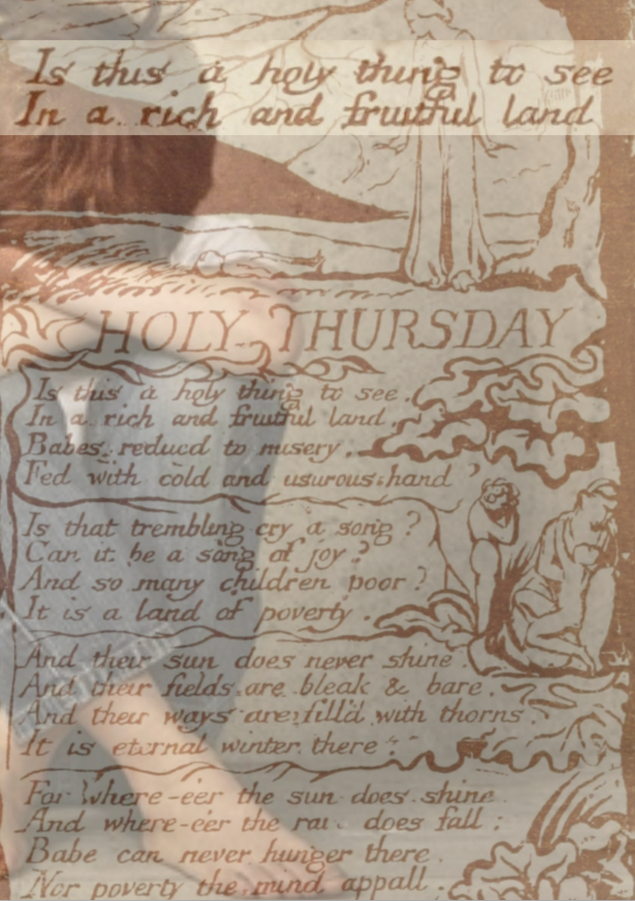

I am your Rational Power O Albion & that Human Form

You call Divine, is but a Worm seventy inches long

That creeps forth in a night & is dried in the morning sunIn fortuitous concourse of memorys accumulated & lost …

So spoke the Spectre to Albion. he is the Great Selfhood

Satan: Worshipd as God by the Mighty Ones of the Earth

Having a white Dot calld a Center from which branches out

A Circle in continual gyrations (Blake, Jerusalem)

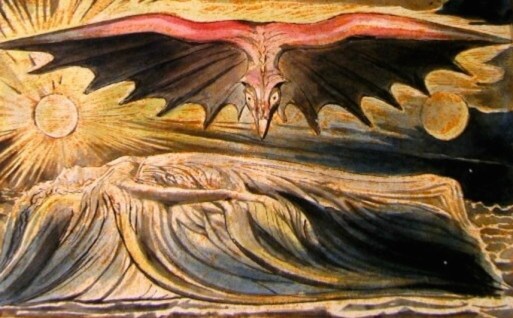

The Spectre

“The Spectre is the Reasoning Power in Man,” Blake succinctly notes in Jerusalem, and throughout his works he consistently links the “spectral” or compulsive aspect of divided and divisive rationality with the contemporary form of human reason itself:

… it is the Reasoning Power

An Abstract objecting power, that Negatives every thingThis is the Spectre of Man, the Holy Reasoning Power

And in its Holiness is closed the Abomination of Desolation.