A BLAKE NEW WORLD: The place of Sense Perception and Imagination in William Blake and Aldous Huxley

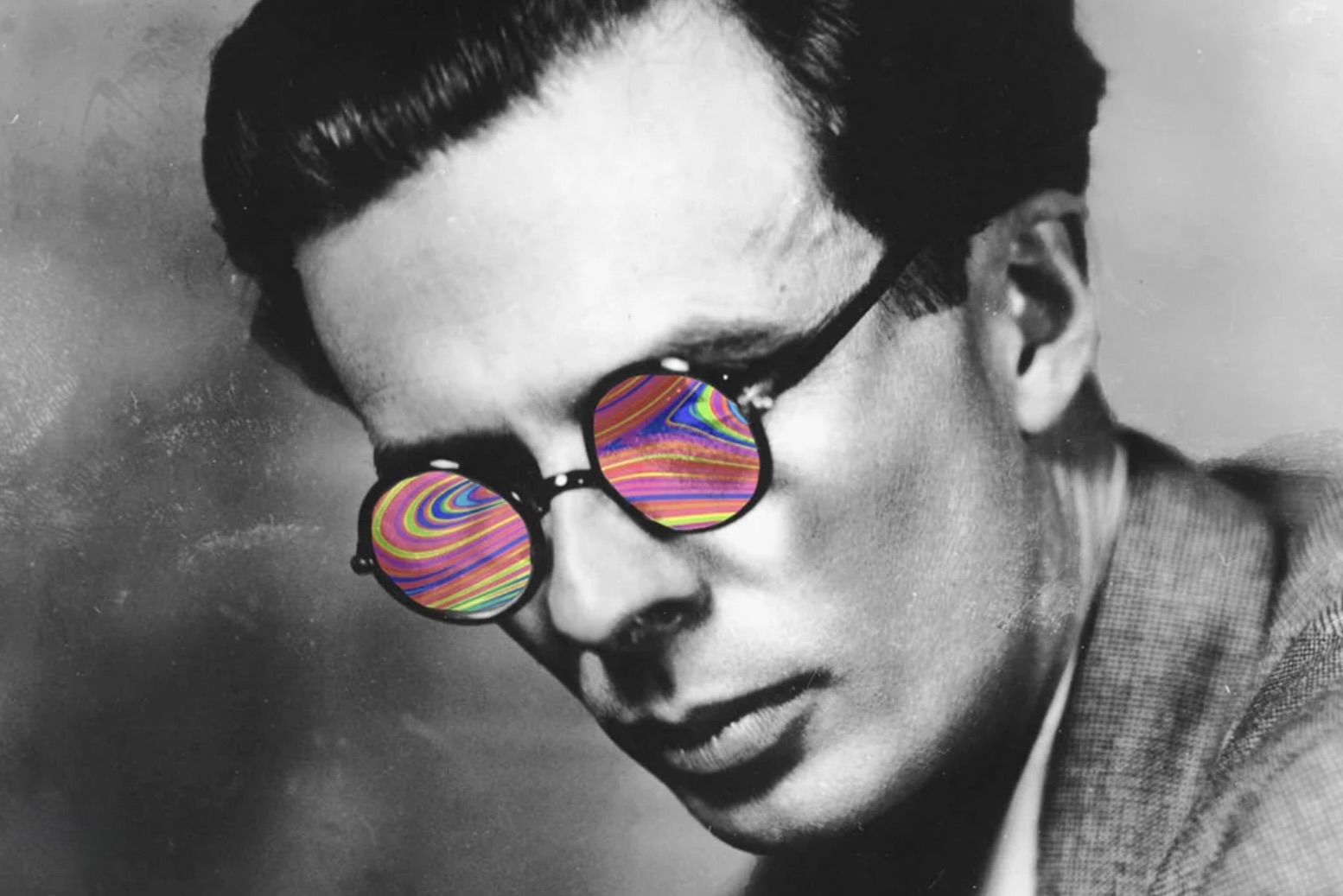

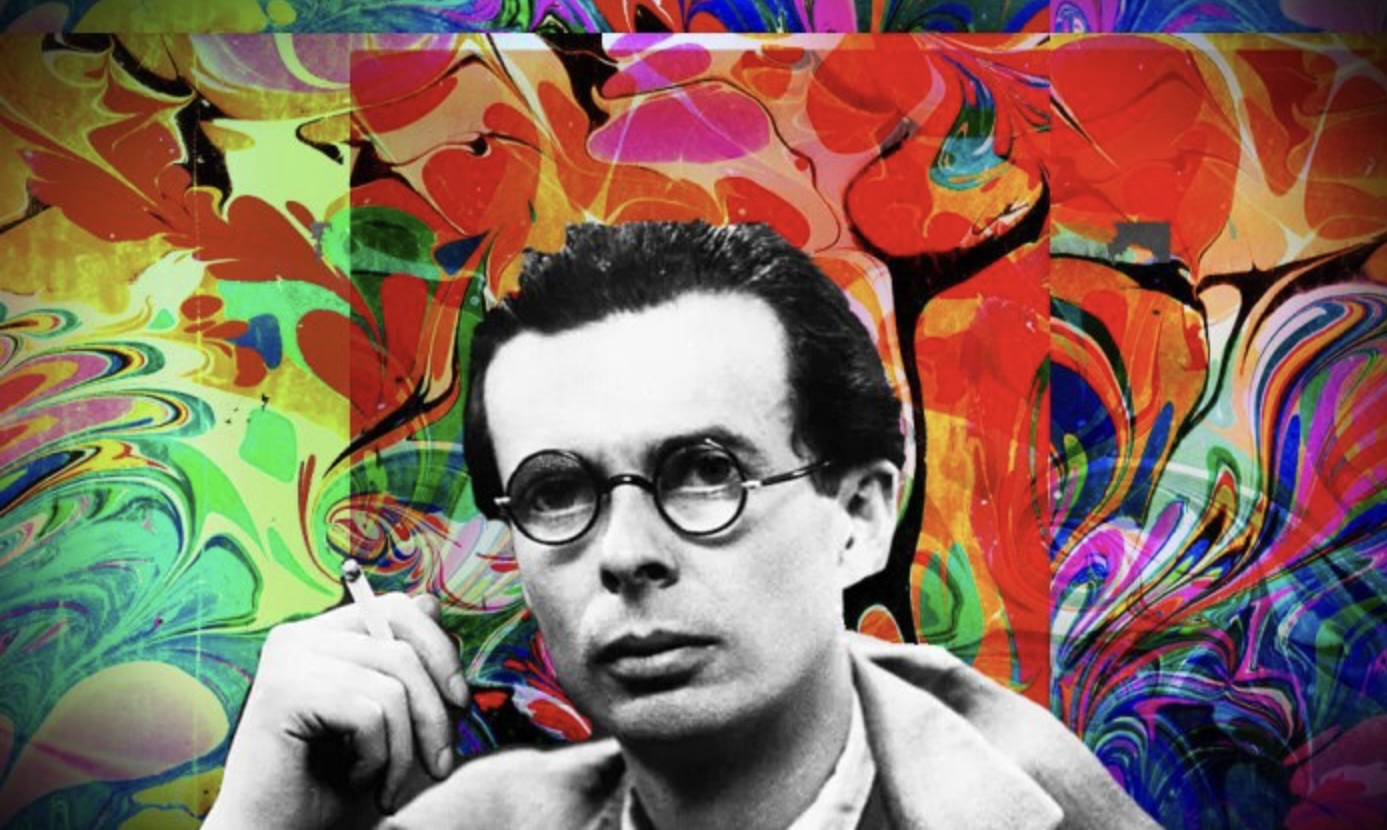

Aldous Huxley and the Doors of Perceiving

Introduction: Opening the Flower of Mescaline

His interest piqued by psychological research on the drug, in 1953 Aldous Huxley swallowed four-tenths of a gram of mescaline with the hope that his experience would lead to a better understanding of the mind’s role in human perception.

Mescaline is a relatively innocuous hallucinogen found in several species of cacti, the most well-known being Peyote, a small plant that many of the native peoples of the American Southwest and Mexico respect as a divine gift. Western science has approached the drug’s effects more pragmatically, studying the chemical and psychological changes that accompany mescaline intoxication, but for the more personally-driven experimenter it has not lost its philosophical allure.

Heaven in a wild flower: Mescaline is a naturally occurring psychedelic that comes from the Mexican peyote cactus (Lophohora williamsii)

“This is how one ought to see, how things really are” – Aldous Huxley

Huxley approached his experiment conscious of both the scientific and philosophical issues surrounding the alteration of consciousness, and recorded his analysis of the experience in two short books, The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell. A discerning glance at the titles of these two works suggests a direct relationship with Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, but the degree to which Blakean concepts actually form the foundation for Huxley’s reflections has not yet been thoroughly examined.