The Longing for Peace and Liberation from Contemporary Domination Systems

Because of the importance of Christmas, how we understand the stories of Jesus’s birth matters. What we think they’re about – how we hear them, read them, interpret them – matters. They are often sentimentalised. And, of course, there is emotional power in them. But the stories of Jesus’s birth are more than sentimental. The stories of the first Christmas are both personal and political. They speak of personal and political transformation. Set in the first-century context, they are comprehensive and passionate visions of another way of seeing life and of living our lives.

“they are about a different way of seeing”

They challenge the common life, the status quo, of most times and places. Even as they are tidings of comfort and joy, they are edgy and challenging. They confront “normalcy”, what we call “the normalcy of civilisation” – the way most societies, most human cultures, have been and are organised. The personal and political meanings can be distinguished but not separated without betraying one or the other. They are about us – our hopes and fears. And they are about a different kind of world. God’s dream for us is not simply peace of mind, but peace on earth.

The First Christmas in Context

Symbol of Caesar Augustus. “Divi F.” stands for “Divi Filius” – Son of God, or Son of the Divine

The first-century context is not simply historical, but also theological. It concerns the conflict between an imperial ideology and a theology grounded in the God of Israel as known in the Bible and Jesus.

Our twenty-first-century context is also historical and theological. What do the stories of Jesus’s birth mean in our contemporary historical context? To say the obvious, America is in the powerful and perilous position being the empire of our day. As we will see, the stories of the first Christmas are pervasively anti-imperial.

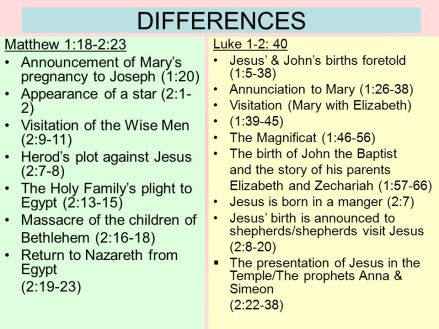

Note the plural: we do not have a story of the first Christmas, but two. They are found in Matthew and Luke, two of the four gospels of the New Testament. These stories are quite different from each other. Seeing these differences is utterly crucial to an understanding of their meaning.

In Matthew’s story, Joseph is the main character. Mary neither speaks not receives any revelation. There is no story of the birth itself, no swaddling clothes, no stable, no manger, no angels singing no shepherds on the night of Jesus’s birth. All of these are from Luke. Apart from Joseph, it is King Herod who drives the action in the story (his meeting with the “three wise men” from the East; his decision to kill all children under the age of two in Bethlehem – which in turn forces Joseph and Mary to flee to Egypt; and the slaughter of the innocents). Indeed, it is surprising how little of Matthew’s birth story is about Jesus; Jesus is almost “off stage.”

Luke’s story focuses initially on the story of the conception of John the Baptist and how his elderly parents (Zechariah and Elizabeth, who have strong links with stories in the “Old” Testament, represented here by Elizabeth’s age) were foretold by an angel of John’s birth. Elizabeth appears in the story again when Mary (now pregnant with Jesus) visits her. Women play much more prominent roles in Luke. For much of Luke’s birth story, Mary is the central character. Indeed, a central feature of Luke’s whole gospel is his emphasis on women, the marginalised, and the Holy Spirit.

“What do the stories of Jesus’s birth mean in our contemporary historical context?”

The Two Nativity Stories

Traditional Nativity Scene? There are “no swaddling clothes, no stable, no manger, no angels singing, no shepherds” in Matthew, Mark or John. Luke adds them to emphasise ideas of the dispossessed and lowly – a different kind of “kingdom”

Usually we do not hear these two stories of the first Christmas as whole and distinct narratives. Rather, we hear them through filters. One common filter is “harmonising” them, either by combining them into one story or preferring one version and ignoring contradictions from the other.

For example: where did Mary and Joseph live before Jesus was born? Most people would answer: Nazareth. In Luke’s story, Mary and Joseph live in Nazareth, and when it’s time for her to give birth, she and Joseph journey to Bethlehem, where there is no room at the inn and so Jesus is born in a stable. But in Matthew, Mary and Joseph already live in Bethlehem, where Jesus is born – at home – and Nazareth only becomes their home after their return from Egypt after Herod’s death.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with harmonising; but reading each as a separate narrative and paying attention to the details of the texts enriches these stories and adds greatly to their power. Meaning grows larger, not smaller. Interestingly, in Mark’s gospel (the first one to be written, about twenty years before Matthew and Luke), there is no mention at all of an extraordinary birth of Jesus, and no mention of it either in the letters of Paul, which were written even earlier than Mark. This suggests that stories of Jesus’s birth were not of major importance to earliest Christianity.

The Nativity Story: Fact or Fiction?

Nativity Maths: “The Enlightenment led many people to think what is true is what can be experimentally measured and verified”

A recent TV special on the birth of Jesus posed the question this way: are these stories fact or fable? For many people, Christians and non-Christians alike, these are the two choices. But there is a third option that moves beyond the choices of fact or fable, which is to see them as parables or metaphors. In earlier centuries, their factuality was not a concern for Christians. Nobody worried about whether they were factually true. All of the interpretive focus was on their meaning. This way of seeing the stories has become impossible in the modern world, and the reason is the impact of the Enlightenment, and the emergence of modern science and scientific ways of knowing.

The Enlightenment led many people to think that truth and factuality are the same – that what is true is what can be experimentally measured and verified. In their minds, if these stories aren’t factual, then they are not true. Christian biblical literalism is equally focused on this Enlightenment notion of factuality, and it is rooted in a form of fact fundamentalism. As such, it is not ancient, but a product of the recent past.

The Importance of Parable, of Right Brain Understandings of Truth

There is no non-interpretive way of reading the birth stories. Every way of reading them involves an interpretive decision about the kinds of stories they are. We argue that the nativity stories are best understood as neither fact nor fable, but as parable. Parable is a form of speech, just as poetry is a form of speech, and it is the form of speech that was the most distinctive style of teaching of Jesus himself.

There is no non-interpretive way of reading the birth stories. Every way of reading them involves an interpretive decision about the kinds of stories they are. We argue that the nativity stories are best understood as neither fact nor fable, but as parable. Parable is a form of speech, just as poetry is a form of speech, and it is the form of speech that was the most distinctive style of teaching of Jesus himself.

“The meaning of a parable does not depend upon its factuality”: from Disney to George Orwell to the Bible, such stories aren’t dependent on quantitive measurements or empirical verification for their meaning. In fact to read such stories in this way is to completely misread them.

Parable as a form of language is about meaning, not factuality. The meaning of a parable does not depend upon its factuality. The parable of the good Samaritan, for example, does not depend on its literal truth: if someone says there really had to have been a Samaritan who compassionately came to the aid of a victim of a violent robbery or else the story isn’t “true”, then most people would say “No, that’s not the point.” Such parables matter, and are truthful, even though they’re not factual, even though they’re “made-up stories”. For those who have ears to hear, they are full of truth.

To see these stories as parables means that their meaning and truth do not depend on their factuality. Indeed, being concerned with their factuality risks missing their meaning and truth. Parables are a form of metaphorical language. The metaphorical meaning of language is its “more-than-literal” meaning, the capacity of language to carry a surplus of meaning. A parable is a narrative metaphor, a metaphorical narrative, whose truth lies in its meaning.

Parables and Historicity: The Meaning of the Nativity Stories lie in their Historical Context

A historical approach to the nativity stories means setting these ancient parables in their first-century context. What did these stories mean for the Christian communities that told them near the end of the first century? Just as the parables of Jesus become powerfully meaningful in their first-century context, so do early Christian stories about Jesus. A striking feature of his parables was that they were subversive stories.

A historical approach to the nativity stories means setting these ancient parables in their first-century context. What did these stories mean for the Christian communities that told them near the end of the first century? Just as the parables of Jesus become powerfully meaningful in their first-century context, so do early Christian stories about Jesus. A striking feature of his parables was that they were subversive stories.

‘The Massacre of the Innocents’ by Lucas Cranach the Elder (c. 1515)

They subverted conventional ways of seeing life and God. They undermined a “world”, meaning a taken-for-granted way of seeing “the way things are”. Jesus’s parables invited his hearers into a different way of seeing how things are and how we might live. As invitations to see differently, they were subversive. Indeed, perhaps seeing differently is the foundation of subversion.

Like his parables, the birth stories are subversive. They subverted the “world” in which Jesus and early Christians lived. This was the contemporary world of empire, of Rome, of contemporary domination systems. The nativity stories frame a clash, and a choice, between the kingdom of Rome and the kingdom of God. This difference needs to be carefully diagnosed, since the first-century emperor Caesar Augustus was entitled Lord, Son of God, Bringer of Peace, and Saviour of the World. The authors of the birth stories of Jesus deliberately challenge the rule of Caesar by applying these titles to Jesus, and offer their hearers a choice of kingdom.

“The nativity stories frame a clash, and a choice, between the kingdom of Rome, of contemporary domination systems. and the kingdom of God”

That term “kingdom” emphasises not so much territorial space as a mode of economic distribution, a type of human organisation, and a style of social justice and global peace. This tectonic clash of kingdoms is the context of our Christmas texts, and reverberates throughout the centuries to our own day. The tectonic clash of the kingdom of Rome versus the kingdom of God – with each kingdom claiming to the be earth’s fifth and final one – is the living context for those Christmas stories of Matthew and Luke.

A Choice of Kingdoms: Rewriting the story of Peace

The basis of Pax Romana: the military machine – the only sort of peace the Romans knew was “peace through conquest”. The earlier prophets and gospel writers directly challenged this conception

Ideological power is the monopoly or control of meaning and interpretation. The titles of the Roman emperor Caesar Augustus, for example, were: Divine, Son of God, God, Lord, Redeemer, Liberator, and Saviour of the World. To use any of them of the newborn Jesus would be either low lampoon or high treason. For Augustus and for Rome, the title of Bringer of Peace, meant a specific form of peace: peace through conquest, peace through violence, peace through victory. This lay behind the famous and much-trumpeted idea of Pax Romana.

But for the Hebrews living under Roman domination in the first century, this “peace” was one of brutality, poverty, and oppression, and it vividly evoked and recalled for them earlier traumatic times of enslavement and external rule: first by the Pharaoh in Egypt (until they were redeemed by Moses, leading them out of Egypt) and then the Babylonian captivity and exile, and the longing for a deliverer, to ransom captive Israel.

These ‘advent’ carols express a longing for release from political and economic enslavement, and the hopes for a new spiritualised and peaceful form of society: ’emmanuel’

These centuries-old sentiments and longings were sparked again in the first-century, and the renewed form of Roman subjugation. These wishes and longings are what drive the narratives of the “nativity” – the desire for a new birth, a new earth, a different sort of peace, a different sort of society.

Matthew therefore deliberately frames Jesus as the “new” – that is, renewed – Moses, a redemptive figure who can lead their society out of enslavement and oppression, and this is why his birth story constantly invoked parallels with the earlier stories of Moses’s birth: an evil ruler (Pharaoh/Herod) plots to kill the newly born Jewish males, and thereby engenders the life of the predestined child, who is only saved by divine intervention and heavenly protection (Exodus 1-2). Even if we do not catch that parallel immediately, anyone in the first century CE would see it as the most striking parallel between the birth story of Jesus in Matthew 1-2 and that of Moses in Exodus 1-2. This is a major clue to Matthew’s intention in his Christmas story as overture to his gospel.

Jesus represented – incarnated – a new way of seeing and a different way of being. As an embodiment of the radical Right Hemisphere take on the world he represented a huge challenge to the Urizenic domination systems of his day – and indeed of our own day.

Prince of Peace versus the Prince of Peace

Crucially, this choice of what sort of world was possible, and therefore what sort of figure was to embody it, hung on the contested term “peace”. Was peace to be achieved through violent victory over one’s enemies (the Roman way) or through nonviolent resistance and justice (as Jesus believed and taught)? Was it to be through a military saviour, or through mental fight. The original authors of the birth stories believed that our world has never established peace through victory. Victory established not peace, but lull. Thereafter, violence returns once again, and always worse than before. We face a similar choice each Christmas. Do we think that peace on earth comes through “Caesar” or through “Christ” – through violent victory or nonviolent justice?

Crucially, this choice of what sort of world was possible, and therefore what sort of figure was to embody it, hung on the contested term “peace”. Was peace to be achieved through violent victory over one’s enemies (the Roman way) or through nonviolent resistance and justice (as Jesus believed and taught)? Was it to be through a military saviour, or through mental fight. The original authors of the birth stories believed that our world has never established peace through victory. Victory established not peace, but lull. Thereafter, violence returns once again, and always worse than before. We face a similar choice each Christmas. Do we think that peace on earth comes through “Caesar” or through “Christ” – through violent victory or nonviolent justice?

Christmas is not about tinsel and mistletoe or even ornaments and presents, but about what means will we use toward the end of peace from heaven upon our earth. Or is “peace on earth” but a Christmas ornament taken each year from the attic or basement and returned there as soon as possible?

Botticelli’s painting ‘Mystic Nativity’ (c.1500) was painted during a time of deep unrest and conflict in Italy, as the inscription at the top of the painting references. It captures the ongoing longing we have for a more peaceful, integrated world. It’s also the first depiction in western art of angels (or indeed anyone) hugging. “Hugging releases oxytocins, a self-manufactured chemical. If we hug each other more and love each other more, then we’re making a commitment to move closer to one another – it’s an essentially optimistic act” (Russell Brand).

This is an edited version of Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan’s book The First Christmas: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus’s Birth. To read the full book please click here.