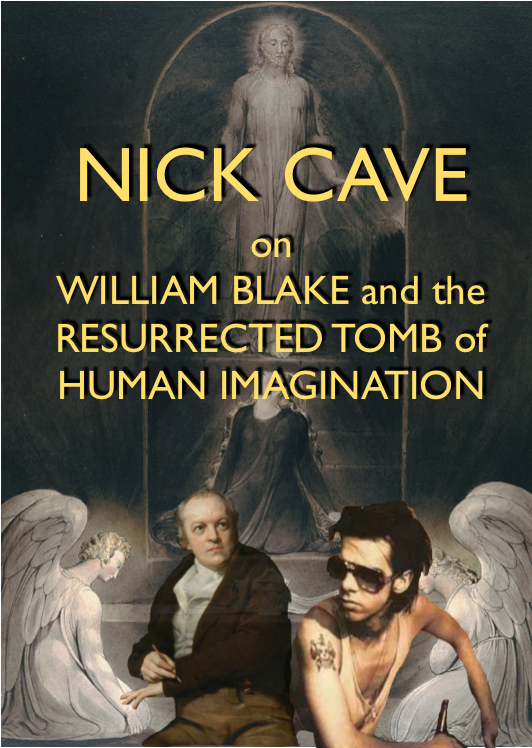

The Marriage Hearse: Blake, Jesus, and the Critique of Marriage and Family Values

Why Mr Blake Cried: Monogamy, Matrimony and the Mind-Forg’d Manacles

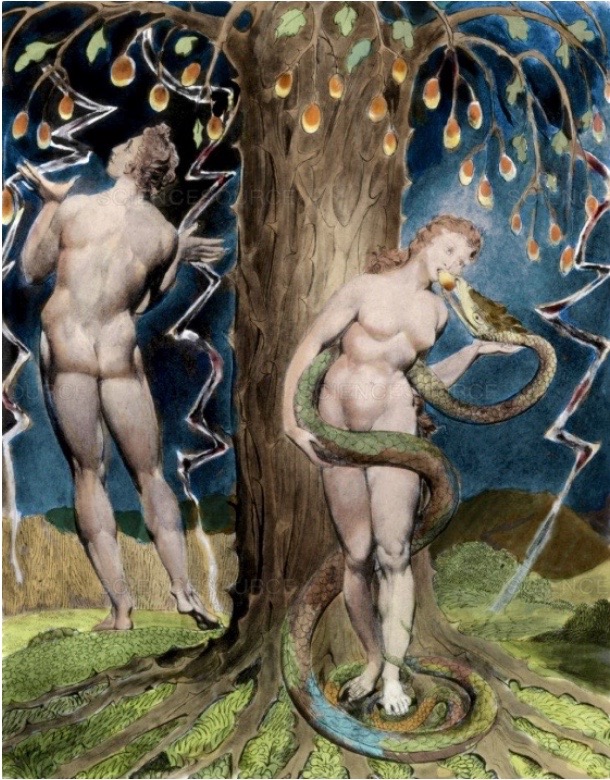

In his fascinating exploration of the ideological status and function of traditional marriage and the role of ‘family values’, American theologian Theodore W. Jennings shows how in the Bible Jesus actually radically subverts these institutions and ways of relating, seeking to replace them with more inclusive, equal, and genuinely socially integrative forms of living. It is interesting in this respect that one of the first things that many spiritual communities do is to replace the atomising, inward-looking, emotionally toxic and politically hierarchical structure of the ‘family’ with more open and egalitarian forms of living. Though in contemporary society, as in Jesus’s day, ‘The Family’ is held up as integral to its power structure and affective organisation of stratified, socially isolated, and authority-based dynamics, which the institution of The Family both transmits and reflects, another way of living, and of being is possible.

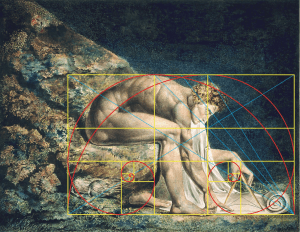

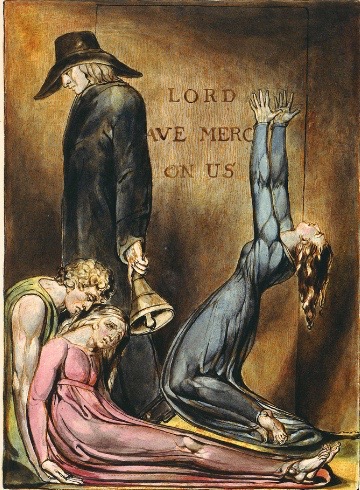

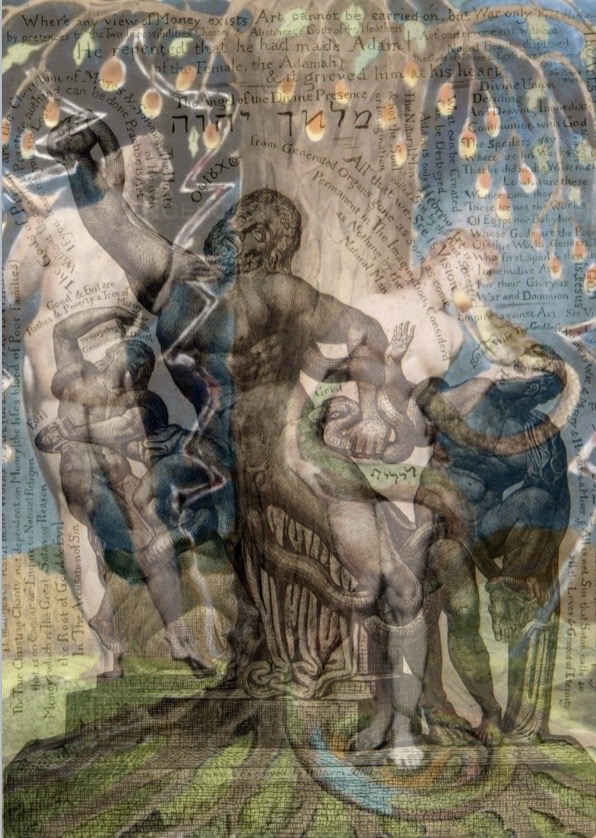

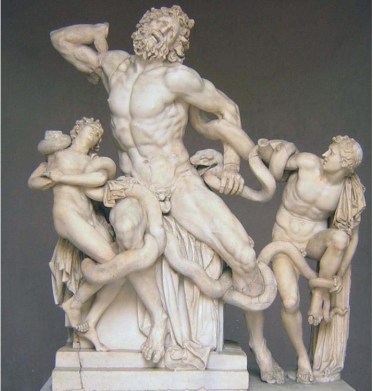

Breaking the ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ that weld us to these old ways of thinking – and more importantly ways of feeling – was one of the central tasks of Jesus’s mission, and was both echoed and developed by the generation of radical poets and thinkers of Blake’s day, including Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft, Rousseau, and of course Blake himself. Before a more awakened and liberated form of society can emerge, Blake suggests, we have to transcend our existing shackles (it is no coincidence that Jennings for example calls one of his chapters ‘Marriage, Family, and Slavery’ – echoing Wollstonecraft’s earlier critique of this institution for the regressive and imprisoning situations and spaces it generates). And in order to do that, we first need to understand what the concept of The Family actually is.

According to Professor Henry Corbin, o

According to Professor Henry Corbin, o