A New Heaven and a New Earth: William Blake and the Everlasting Gospel, by Jackie DiSalvo

Mysticism: The Highest State of Communism, by Jackie DiSalvo

Blake called his Christianity “The Everlasting Gospel”, and as he articulates in that poem, the affirmation of man’s divinity implies a rejection all inequality and authority:

This is the race that Jesus ran

Humble to God Haughty to Man

Cursing the Rulers before the People

Even to the temples highest Steeple …

If thou humblest thyself thou humblest me

Thou also dwellst in Eternity

Thou art a Man God is no more

Thy own humanity learn to adore.

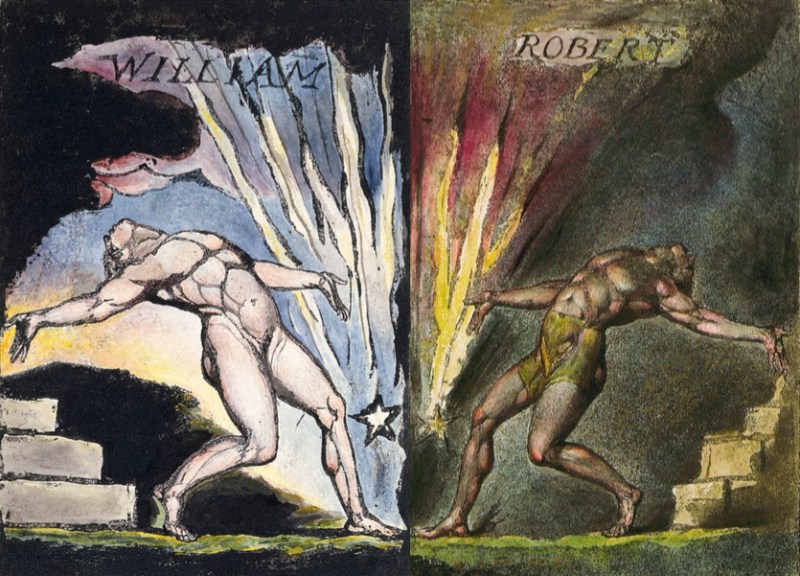

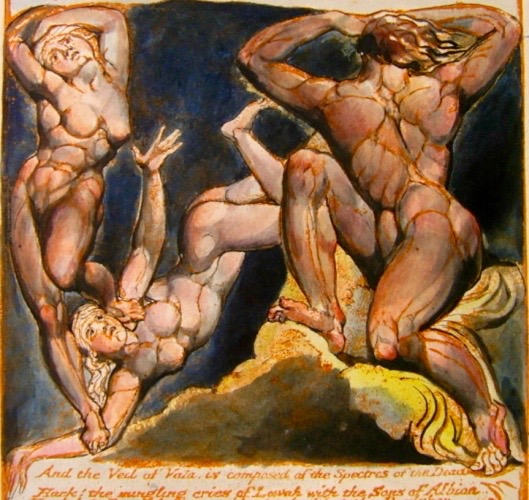

Blake’s humanistic Christianity has been acknowledged by most critics. What must be understood, in addition, is that his use of the myth of Albion, trinitarian doctrine, and the idea of a “mystical body of Christ” demands that we read The Four Zoas as a myth which is simultaneously psychological and social. “What are the Natures of those Living Creatures [the Zoas],” Blake tells us, “no Individual Knoweth” , for they evoke a social reality lost to fallen man.

Watts gained a large following in the San Francisco Bay Area and wrote more than 25 books and articles on subjects important to Eastern and Western religion, including The Way of Zen (1957), one of the first bestselling books on Buddhism, and

Watts gained a large following in the San Francisco Bay Area and wrote more than 25 books and articles on subjects important to Eastern and Western religion, including The Way of Zen (1957), one of the first bestselling books on Buddhism, and