Rod Tweedy reviews the book War against War! by Ernst Friedrich

On May Day 1924 Ernst Friedrich published a collection of photographic images of the atrocities of World War I, hoping to use the relatively new medium of photography as documentary evidence to challenge the orthodox presentation of war. As Douglas Kellner has remarked, “Friedrich hoped that when they actually saw the reality of modern warfare, people everywhere would become more critical of war, the military, and militarism.”

The book was called War against War!, and the photographs made an immediate and lasting impression on his contemporaries, both within and outside of Germany. The images attracted even greater attention when he put them in the window of his newly-opened Anti-Kriegs-Museum in Berlin, the first international anti-war museum (opened in 1925).

Perhaps testimony to their unnerving power, the museum was subsequently targeted by Nazi storm troopers, and on the same night that the Reichstag was burned the whole collection was destroyed. Unperturbed, Friedrich re-opened it a few years later in Belgium where, following their invasion of 1940, the Nazis again shut it down. The museum finally re-opened in Berlin in 1982: Friedrich’s grandson, Tommy Spree now runs it.

Outlasting all the armies of the Third Reich: three incarnations of the Anti-Kriegs-Museum in Berlin, the first international anti-war museum

The end of Empire: Shelley’s poem reveals the death-drive and therefore transience of imperialism

I find the history of this book very poignant – that the work of an anti-war campaigner in the 1920s is still being remembered and still reverberating today, and that these small photographs have outlived all the divisions of the Third Reich. As William Blake once noted, speaking of the work of another radical: “is it a greater miracle to feed five thousand men with five loaves than to overthrow all the armies of Europe with a small pamphlet?” (Blake was referring to the work of Thomas Paine, who also used literature and knowledge in his fight for a freer and more open society.) Sometimes the little acts of remembrance and continuation are more profound and meaningful than the big state occasions and the glitzy television spectacles. Sometimes the final victors of history are the most surprising, as Shelley intuited in ‘Ozymandias’; sometimes the everyday acts of courage and humanity outlive all of the bombast and bunting.

Seeing War Today

Friedrich’s own “small pamphlet” has recently been re-published by the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, and ninety years on it loses none of its relevancy or indeed its power to punch. Friedrich’s hope was to bring home the mundane, brutalizing reality of war – through the very medium that many wars have been fought – images. The book is, he says, “a picture of War” – you can sense in Friedrich that desire to utilize the “truthfulness” of the photographic medium, to enlist it in order to show the dreadful “truthfulness” of war – “a picture of War, objectively true and faithful to nature, photographically recorded for all time”. If we’ve lost this view of photography, or are more wary of it’s objectivity today, it’s partly due to the abuses that have been made of it.

Friedrich’s own “small pamphlet” has recently been re-published by the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, and ninety years on it loses none of its relevancy or indeed its power to punch. Friedrich’s hope was to bring home the mundane, brutalizing reality of war – through the very medium that many wars have been fought – images. The book is, he says, “a picture of War” – you can sense in Friedrich that desire to utilize the “truthfulness” of the photographic medium, to enlist it in order to show the dreadful “truthfulness” of war – “a picture of War, objectively true and faithful to nature, photographically recorded for all time”. If we’ve lost this view of photography, or are more wary of it’s objectivity today, it’s partly due to the abuses that have been made of it.

The book itself is a mixture of drawings, posters, children’s war games (today these might be represented by Call of Duty, Medal of Honor, Battlefield 3) – to suggest where the military training actually starts – as well as the war photographs themselves. The force of the images is partly in their juxtaposition: soldiers eager to go to war in 1914 on one page, next to a heap of tangled corpses on the next – suggesting the actual nature of the of the “field of honour” into which they are unconsciously marching. But it also implicitly points out the highly selective editing of photography that goes on in mainstream publications – how pictures from the very same reel might be selected, filtered, in order to bolster whatever narrative the newspaper is taking. A German father looks proud, in his soldier’s uniform, amongst trees in France; two days later we see him again, dead and faceless amongst the mud. Perhaps unsurprisingly only the first made it into the Illustrated Family Journal.

Marching into ‘the Field of Honour’

These are not easy pictures to look at – like the later war photography of Don McCullin they ask us not to look away from the reality of war. This touches on one of the many paradoxes and ambiguities of a medium that’s based on wanting you to look at it. Neither are these images “Art”: they are ordinary snapshots taken from the Front, not composed or well-lit – as we expect photographs and oil paintings to be. Nor are they reproduced here on fine paper. But that is part of their point, and power – these photos are everyman, they are meant only to register a reality – not to airbrush it or rearrange it. All they are saying is that this did actually once happen, and this is what it did actually look like – and it’s a view of war that no modern Jeremy Paxman documentary, or learned Niall Ferguson tome, or Lloyd Georgean rhetoric, can really capture or come close to.

In all of those verbal commentaries there are inevitably interpretations, biases, agendas, justifications – often quite disturbing and manipulative ones. But here we just see – both the propaganda photos (such as one of Kaiser Wilhelm walking nonchalantly along some duckboards specially constructed so he wouldn’t get his boots dirty) and the other less glamorous ones (a corner of a field where rag-like men lie dead, sprawled and humped over the earth – disappointingly not at all like the fun and energetic ‘paper soldiers for cutting out and pasting’ shown earlier).

The photographs also record the gulf between those who make the orders and those who do the fighting. They suggest the absence of representation of the one in the other. Generals sipping tea or surrounded by their greyhounds in the backstreets of an occupied town; a heap of tangled bodies dead in a muddy trench, to which Friedrich has added the caption: “At the front: the Crown Prince is not present”. They also suggest cause and effect. The cause: a soldier blasting out a jet of ‘liquid fire’ in the new flame-throwers that the war developed. On the next page, the effect: most of the human body torched by the burning gasoline is simply not there. What is, – scraps of face, a boot – is badly charred.

Friedrich’s arrangement of these photos is obviously the result of an editing, a selection in itself; to suggest a way of viewing the images of war. In that respect it is like the usual editing of photos for propaganda magazines and recruiting adverts. But, significantly, it is one that evokes context, that holds the gaze – it reveals that throwing burning gasoline at another human being does actually have consequences. It makes you look at those consequences. This makes it completely unlike the standard lens through which we’re usually invited to view war – a way of seeing that is, like so many other aspects of the modern left-brain mode of attention, completely context-free.

Friedrich’s arrangement of these photos is obviously the result of an editing, a selection in itself; to suggest a way of viewing the images of war. In that respect it is like the usual editing of photos for propaganda magazines and recruiting adverts. But, significantly, it is one that evokes context, that holds the gaze – it reveals that throwing burning gasoline at another human being does actually have consequences. It makes you look at those consequences. This makes it completely unlike the standard lens through which we’re usually invited to view war – a way of seeing that is, like so many other aspects of the modern left-brain mode of attention, completely context-free.

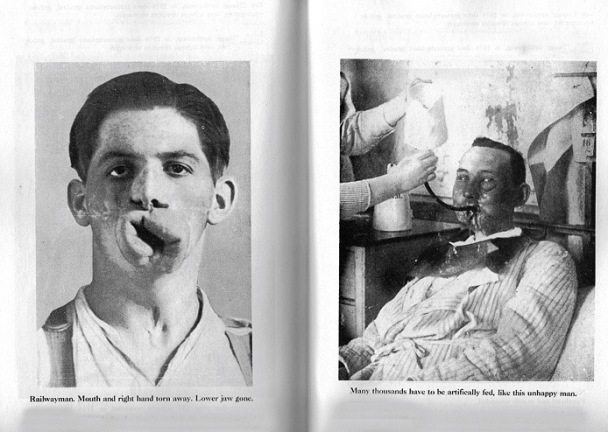

They are pictures of extremes: soldiers smoking, making merry. Soldiers undergoing extensive reconstructive face surgery, their mouths and jaws blown off. There is a familiar unease here: a sense that the one is somehow related to the other, however indirectly or unconsciously. Indeed, there’s a suggestion that the transient and perhaps superficial highs are somehow connected to or responsible for the abject lows, and on some level aware of this. That all of the successes and wealth within the current system is ultimately at the price of a dreadful human impoverishment and suffering (sweatshops, wars, chronic mental health) that we know goes on but which we are not usually invited to consider: virtual heaven at the expense of actual hell.

Look at what war is

One of the most trenchant aspects of Friedrich’s work is its persistent questioning – he asks what “heroic death”, or “glory”, or “honour”, actually mean or corresponds to in these situations. There is one particularly upsetting image – which he’s ironically captioned “A ‘meritorious’ achievement” – that movingly brings home the potential insanity of this language, of these ridiculous awards systems. Perhaps these are similar to how other forms of marketing or advertising work, in inverse ratio to the reality: Gilette’s ‘The Best a Man Can Get’ (shaving is a humdrum nuisance); McDonald’s ‘I’m Loving It’ (this tastes like cardboard); the Military’s ‘Pour le Mérite’ (for those who die as cattle).

This is not to dismiss the extraordinary acts of bravery that many soldiers perform, or the extreme difficulties they endure, but simply to note the unease with how these are formally recognised, and what they actually signify – especially when the causes of going to war are so uncertain and problematic. Siegfried Sassoon was one of many soldiers who recognised this unease, throwing his Military Cross ribbon (awarded to him for “conspicuous gallantry”) into the Mersey in 1916 to register his profound disillusionment with the war and those responsible both for it and for the manufacture of its medals.

“I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest” (‘Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Statement’, Siegfried Sassoon). The government’s response was to bundle Sassoon into a military psychiatric hospital in Scotland. This temporarily muffled the impact of his statement (as it was intended to), but it also eventually led to an unexpected encounter. At the hospital (Craiglockhart) he met another young soldier-poet, Wilfred Owed, whose verse was galvanised by Sassoon’s presence. Indeed, the meeting led to writing that would eventually challenge the whole culture of militarism far more powerfully than a simple court-martial of Sassoon would ever have done.

In these contexts, as Friedrich suggests, military medals, honours, and titles, often seem to be our way of masquerading unsettling truths about what’s going on, about what we are actually doing, just as poppies are also symbols of forgetfulness. The cemeteries for the dead in France and Belgium are poignant and dignified, and rightly so, but even they don’t convey the dreadful reality of the deaths that put them there, in the way that these photographs, assembled by Friedrich, do – the rigor mortis arms, the absence of limbs, the amalgamated heaps.

After a while, looking at photo after photo of these traumatic and brutalizing scenes, all words go. Looking at them becomes a bit like losing one’s moral compass. Maybe this is the testimony of photographs: to move beyond language, truisms, justifications, even articulation of outrage. What can you say when you’ve seen men stretched over barbed wire like rotting horses. How can you convey the pity of this all through the bayonets of language, of verse. Wilfred Owen’s achievement was so significant, as both a poet and solider, because he somehow did find the words – brought things back from that place, – although he himself was keenly aware of the inadequacy or inaccuracy of this articulation (“I heard the sighs of men, that have no skill/To speak of their distress”).

After a while, looking at photo after photo of these traumatic and brutalizing scenes, all words go. Looking at them becomes a bit like losing one’s moral compass. Maybe this is the testimony of photographs: to move beyond language, truisms, justifications, even articulation of outrage. What can you say when you’ve seen men stretched over barbed wire like rotting horses. How can you convey the pity of this all through the bayonets of language, of verse. Wilfred Owen’s achievement was so significant, as both a poet and solider, because he somehow did find the words – brought things back from that place, – although he himself was keenly aware of the inadequacy or inaccuracy of this articulation (“I heard the sighs of men, that have no skill/To speak of their distress”).

Wilfred Owen wrote in a letter to his brother in September 1918, shortly before his final return to the front: “I came out in order to help these boys – directly by leading them as well as an officer can; indirectly, by watching their sufferings that I may speak as well as a pleader can. I know I shall be killed. But it’s the only place I can make my protest from.”

The same anxiety that is evident in Friedrich’s work in 1924 – the concern that people may forget, or not even know in the first place, the reality of warfare – was also what drove Wilfred Owen back to the front line, to give a “voice” to the voiceless, as he put it. Friedrich shares Owen’s unease that the true nature of warfare was being concealed by both the home governments and the media and thus misunderstood by the wider public.

This concern reaches from Sassoon, Friedrich and Owen to those calling for greater transparency and accountability in today’s reporting and understanding of war, such as Chelsea Manning. In a recent article Manning has referred to the “disjunction” and “disparity” that exists between the reality of war and the media coverage of it.

Sassoon’s protest was made, as he himself put it, to “help to destroy the callous complacency with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share and which they have not enough imagination to realise.” It was to prod and awaken these imaginations that these writers worked. Each in different ways believed that the stark, sheer reality of war – of men’s faces torn apart (“faces blown half away”, as Bruce Kent strikingly puts it in his compelling new Introduction to Friedrich’s book) was being lost in unreal and untruthful rhetoric of “heroic death” and “fields of honour” – the “old Lies” that Owen also sought to combat.

The Old Lie

Ernst Friedrich

What has been torn away in these photographs is not only the mask of men’s faces but of war itself – the “beautiful phrases”, the old lies. It is the aesthetic nature of all this that is one of the most disturbing and puzzling aspect of Friedrich’s collection (and it may be significant here that he originally hoped to become a sculptor or artist, and later had close links with the Expressionist movement). It’s the same problem that confronted Owen in writing poems, and McCullin in taking pictures: how do you use a medium posited in many senses on beauty, to show not merely the horror, but also how the medium itself is in a sense part of the problem.

Shell Shocked Marine, Vietnam, photo by Don McCullin

In McCullin’s work this paradox is particularly acute, as many of his finest images have such technical accomplishment as to be almost things of beauty, works of art, and yet the subjects are such that deny and repel any hint of this. The instinct with taking a photo, any photo, is surely to make it look good. So how do we to react to horrific images that are beautifully taken? Something about that is troubling. It troubles both the reader and the artist – hence perhaps the haunted nature of McCullin himself, or Owen (“Am I not a conscientious objector with a very seared conscience”).

There is something that is unearthed or unleashed in violence and the brutality of warfare that seems to call into question the whole business of art, – perhaps just as the experience of war calls into question the whole business of morality. All the rhetoric – “the halo and the humbug”, as Friedrich evocatively puts it – both invokes and appeals to it; all the military music, all the sexiness of the recruitment poster. Even the uniforms the Nazis wore by designed by Hugo Boss.

And the same aesthetic of war is still relentlessly cultivated by contemporary manufacturers of video games, and government recruitment adverts, and surely needs to be challenged as much as the ideologies, intellectual justifications, and sexed-up dossiers themselves. The impact of the yearly televised Cenotaph rituals on Remembrance Sunday, as watched through the high definition lens of BBC television, is surely part of its huge appeal, a sort of Olympics Opening Ceremony for the royal family and British Legion – war as spectacle, even if these days it is rather a bruised sense of war.

And the same aesthetic of war is still relentlessly cultivated by contemporary manufacturers of video games, and government recruitment adverts, and surely needs to be challenged as much as the ideologies, intellectual justifications, and sexed-up dossiers themselves. The impact of the yearly televised Cenotaph rituals on Remembrance Sunday, as watched through the high definition lens of BBC television, is surely part of its huge appeal, a sort of Olympics Opening Ceremony for the royal family and British Legion – war as spectacle, even if these days it is rather a bruised sense of war.

Harry Patch, the last British survivor of the 1914-18 war, referred to Remembrance Day as “just show business”. He had seen the horrors and offensive futility of war first hand, and he saw through the Legion’s Remembrance Day charade and all its “macabre piety” just as keenly. As one veteran and former SAS soldier has noted, “The use of the word ‘hero’ glorifies war and glosses over the ugly reality. War is nothing like a John Wayne movie. There is nothing heroic about being blown up in a vehicle, there is nothing heroic about being shot in an ambush and there is nothing heroic about the deaths of countless civilians.” Similarly, D-Day war veteran Jim Radford, the youngest known person to take part in the D-Day landings, has also eloquently questioned the militaristic focus of the Cenotaph events ( ‘D-Day veteran says Remembrance Sunday service is “hijacked” by Royal family’.)

In the brief introductory statements that he provided for his book, Friedrich calls for a true understanding of the hidden motivations and causes of war, usefully citing Plato’s observation that “All wars arise for the possession of wealth”. For Friedrich, behind the smokescreen of morality and holiness, and the propaganda of adventure and reclaiming glory, the object in virtually all wars, when it comes down to it, is “to protect or to seize money and property and power”.

Pro petroleum mori: The hidden causes of war

When money or property or power is threatened, the reaction of the elites, he notes, is to rattle their sabres and call out “The Country is in danger!” And by “Country”, Friedrich nicely points out, they usually simply mean “money-bags”. Believing in one’s country can be a great thing, except when it’s based upon a fabrication – where the word “Country” is simply “the string which ties the robber’s bundle”, as Shelley noted two hundred years ago. This form of patriotism is a constructed fabrication because it is used to mask the power which actually runs the country – the “power of the rich”.

This system is kept in place, Friedrich notes, not only by police and by blatant economic power and coercion, but also psychologically – through propaganda, such as the subtler programmes and neurological processes based on the desire to “command and dominate”, which capitalism in particular so tirelessly appeals to and targets. These processes, Friedrich notes, are replicated everywhere in our divided and unreal societies – in our offices and factories (“the battlefield in the factories”, as he puts it), and even at home, in domestic and sexual relationships (in the wish, for example, to “dominate and command … over his wife and children in his family”). “How many lightly overlook the fact that in one’s own home, in the family, war is being spontaneously prepared” – an acute, and depressing observation. Freidrich acutely refers to this as the need to fight against the “capitalism within yourselves”, in order to eradicate the basis on which it’s constructed.

“The battlefield in the factories”: scene from Fritz Lang’s classic 1927 film Metropolis, predicting the ideologies of class and race of the 20th century. The film was made shortly after Friedrich’s Anti-Kriegs-Museum opened in Berlin.

Like Blake, Friedrich’s response to the culture of militarism is energetic and oppositional, hence the motivational title of his book. He is not an advocate for quietism – for holding hands and tea-cakes, as he rather disparagingly puts it (“Those bourgeois pacifists, who seek to fight against war by mere hand caresses and tea-cakes and piously up-turned eyes”). Indeed, again like Blake, he seeks to reclaim the concept of “fighting”, not in order to denote literal battles fought with equally literal bayonets and flamethrowers, but rather to signify what Blake called “mental fight” – the engaged, dynamic, passionate processes of the human mind.

Mental Fight

For both writers, this engagement involves the whole artillery of human consciousness: reason, empathy, instinct, and above all imagination. Physical war – “corporeal war”, as Blake called it – is presented as a dreadful perversion of this intellectual fight. Thus, instead of using our intense energies and impulses constructively, through passionate debate and dialectic, we are misled into downgrading them, turning the dynamic cultural struggle through which liberty is forged into a crude parody of struggle – into literal defences and attacks, when we should be winning arguments. As Friedrich observes, “True heroism lies not in murder, but in the refusal to commit murder”: one can be engaged, and at war, with the assumptions and platitudes of war itself. Indeed, Friedrich’s whole life is a striking and powerful example of “mental fight” in action.

So what is it that downgrades our imaginations – our way of seeing other human beings – in this way, and turns our energies into destructive, embattled literalisms? Blake suggests that it is based on a restricting, hardening vision that we are encouraged to have of other people – seeing them in terms of narrow self-interest (“selfhood”), and bolstered by a sense of moral self-righteousness. The trouble with self-interest is that it’s so easy to manipulate – one only needs to offer to reduce income tax rates to see this. Moral self- righteousness may give us a momentary sense of superiority and a virtuous rush to the head (an ‘Ego Rush’), but it is ultimately a very isolating and de-humanising way of relating to people. Capitalism, as Friedrich suggests in his introduction, hard-wires itself into this very narrow, prescriptive, and brutalising aspect of our natures in order to perpetuate itself: “There will always be wars as long as Capital rules and oppresses the people.”

The vision that we are encouraged to have of other people, enabling violence towards them

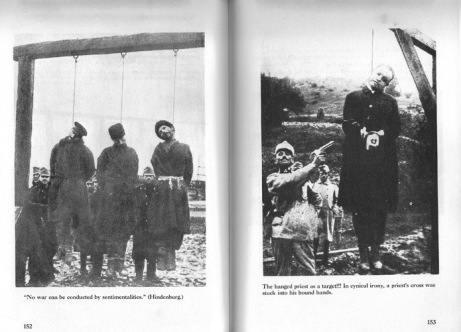

Through its appeals to self-interest and to supposedly moral codes (both of which aim at setting us apart from others) we can be trained to temporarily override our humanity. The ghastly and inexorable pull towards war that ignited the First World War illustrates what happens when we identify too strongly with rigid codes and laws – with bits of paper, which must then be “upheld”. Implicit in this moralising mind-set is an obsession with being “right”, with being “superior” and with being “priestly”. Indeed, Friedrich is furious about the role that the orthodox Church has played in this hardening and divisive process, dedicating his book to “the priests who blessed the weapons in the name of God”. A photograph later in the book shows: “The Bishop of Westminster reviews, alongside of a General, a parade of English Boy Scouts”.

In This Sign Conquer: Friedrich lambasts “the priests who blessed the weapons in the name of God”. It is the Church that enables violence through its endorsement of war, revealing its true servile nature.

The danger of urging a “war on war” of course, is that it simply ends up with more war – replacing one oppressive figurehead or system with another. This happens especially when the desire for liberation is intermixed with feelings of revenge and hatred, rather than with pity, for those currently maintaining the system. The whole point of the insanity of war is that it is us fighting ourselves, and so to see our leaders and elites as other, as less, as deserving of the revolution that’s coming their way, is to fall into a very similar mind-set that they already have: of Them and Us.

The mind-set of Them and Us keeps the whole thing going

So when Friedrich calls on the “war of the deceived against the deceivers”, “the victimised against the profiteers”, or “the tortured against the tortured”, it has to be understood in this context: i.e., not as literal war. Calling one’s opponents “scum” (as I have seen on many of today’s oppositional placards) is, I would argue, the quickest way into the next cycle of deception and victimisation.

How to keep the War going

It is perhaps relevant here to note that our word for “war” is derived from an Old Saxon word meaning “to confuse” or “to perplex” – which is exactly what most governments intent on going to war are so keen on doing. Waking up from this confusion is really what War against War! is all about: “To all regions that have ears to hear I call out but two words and these are Man and Love … And as we all, all human beings, equally feel joy and pain, let us fight unitedly against the common monstrous enemy, War” (Friedrich, introduction to War against War!). As mankind starts to awaken and begins to understand the processes which have been used to keep our shared humanity submerged and unconscious, a subtle but profound shift occurs – from self-interest to social-interest, and from corporeal war to mental war. In Blake’s work, how we view war is ultimately a question of vision, and he urges us to recalibrate and elevate our view of humanity (that is, of our own humanity) in order to challenge and effectively undermine the basis of the pathology that lies behind all appeals to war. This inevitably entails a change in how the human imagination, which is for Blake the basic operating system of man, functions and is perceived:

Urthona [the Human Imagination] rises from the ruinous walls

In all his ancient strength to form the golden armour

For intellectual War The war of swords departed now

“Intellectual War”: this is the true business of the human intellect, Blake suggests, and the literal “war of swords” is a crude perversion of it. As the modern media pervasively demonstrates, war is conducted precisely to stop people thinking, to prevent “mental fight”. “Therefore let us, who are fighters,” Friedrich urges, “join the war against war, let us examine the causes and the nature of war so that, armed with the weapon of knowledge and the sharp sword of the mind, we may emerge victorious from the fight.” And surely that is a war worth fighting.

Never Again: One of the most powerful and poignant commemoration events on Remembrance Sunday actually occurs when all of the TV cameras and all the “show business” – all the royals and generals and politicians and MoD officials – has gone. In the afternoon, a group of British veterans gather to remember the dead and to lay a wreath on the steps of the Cenotaph. They remember soldiers from all countries who lost their lives in conflict, and all of those killed in war including civilians and enemy soldiers. The event is organised by Veterans for Peace UK, an organisation of voluntary ex-services men and women who work to educate young people on the true nature of military service and war. In tribute to Harry Patch they wear a quotation from him on their backs: it simply says ‘War is Organised Murder’. They walk to the Cenotaph under the banner ‘Never Again.’

Rod Tweedy is the author of The God of the Left Hemisphere: Blake, Bolte Taylor, and the Myth of Creation, a study of Blake’s work in the light of modern neuroscience, and the editor of The Political Self: Understanding the Social Context for Mental Illness. He is an active supporter of Veterans for Peace UK and an enthusiastic supporter of the user-led mental health organization, Mental Fight Club. This review was originally written for Veterans for Peace UK and is reprinted by kind permission of VFP UK.

Thank you for this page. It is but yesterday (27 October, 2020) that a former G-G of Australia Peter Cosgrove was featured in the newspapers after his remark that the Army in this country was making our young men ‘killing machines” for battles in other parts of the world.

If I have learnt nothing else in my long life, I have learnt that history is continuous, not episodic.

I will read your article with much interest because I have learned that war – for politicians and such like – has become:

A cure for ‘unemployment’. Have we never heard of leisure?

A way to ‘export’ the unemployment problem.

War is aggravated by the scramble for international markets.

War debt is piled up for future generations to pay off.

A war between A and B is profitable for C.

And so on. I haven’t mentioned the human cost as yet!

LikeLike