William Blake and Me, by Patti Smith

Embrace what you Fear: Being with Blake

My Introduction to Blake

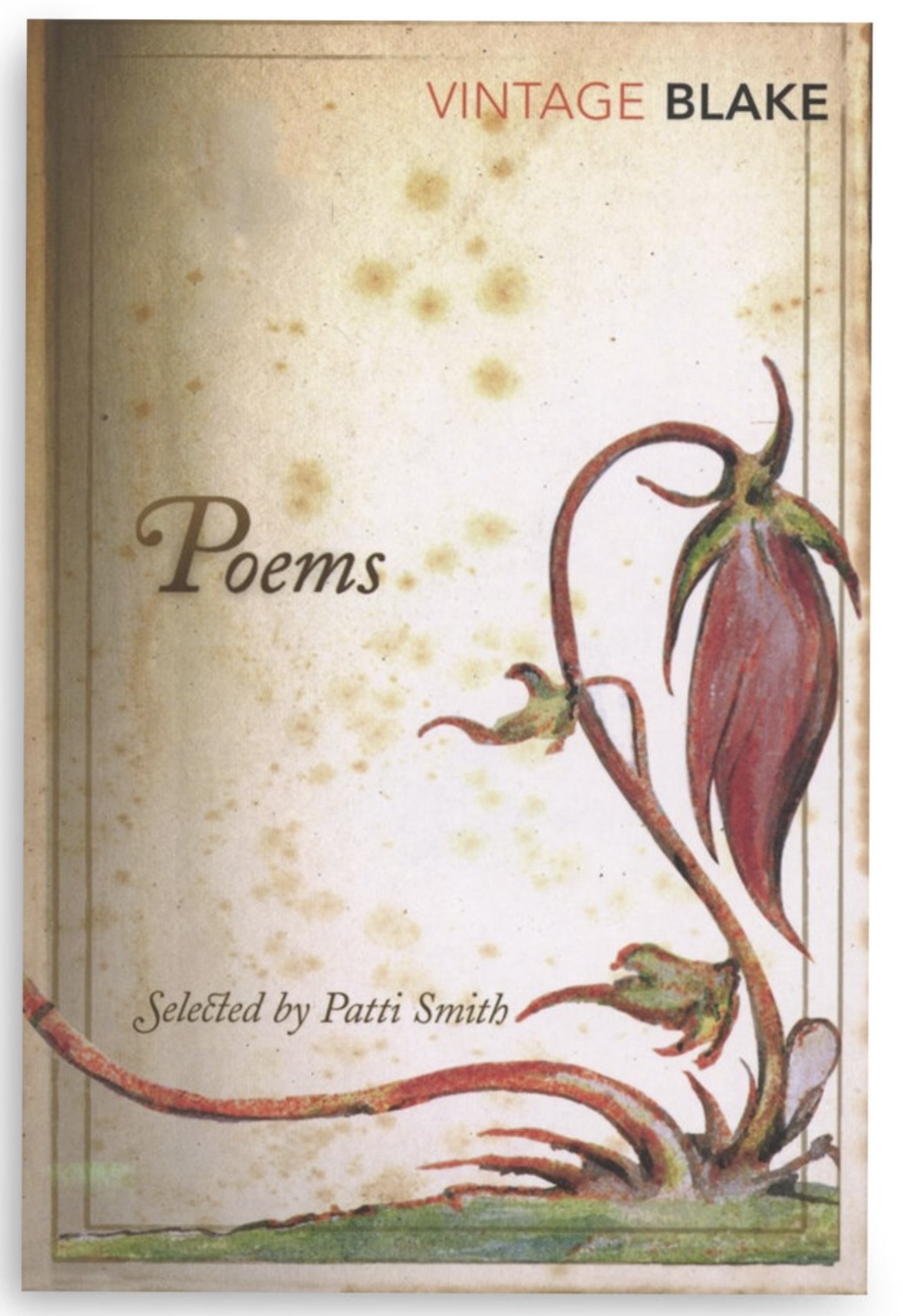

“I can’t imagine my childhood without him. His poems were my companions, my friends. I had pneumonia, I contracted TB, scarlet fever, every childhood disease. And my two favourite books were William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, and the children’s poems of Robert Louis Stevenson.” In 2007, to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Blake’s birth, Smith edited a selection of his verses simply titled Poems — “a bit of Blake, designed as a bedside companion or to accompany a walk in the countryside, to sit beneath a shady tree and discover a portal into his visionary and musical experience.”

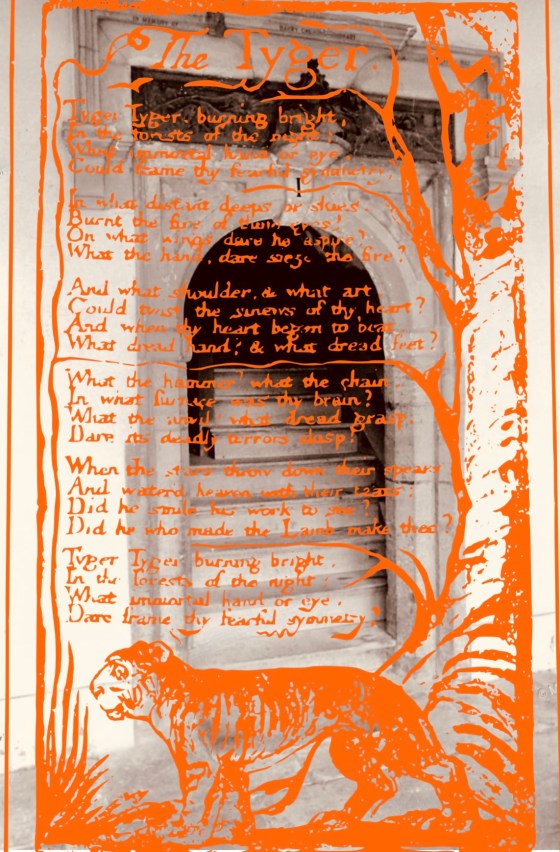

My mother gave me Blake. In a church bazaar she found Songs of Innocence, a lovely 1927 edition faithful to the original. I spent long hours deciphering the calligraphy and contemplating the illustrations entwined with the text. I was fascinated by the possibility that one creates both word and image as did Blake, with copperplate, linen and rag, walnut oils, a simple pencil.

My father helped me comprehend this childless man who seemed to me the ultimate friend of children, who bemoaned their fate as chimney sweeps, labourers in the mills, berating the exploitation of their innocence and beauty.

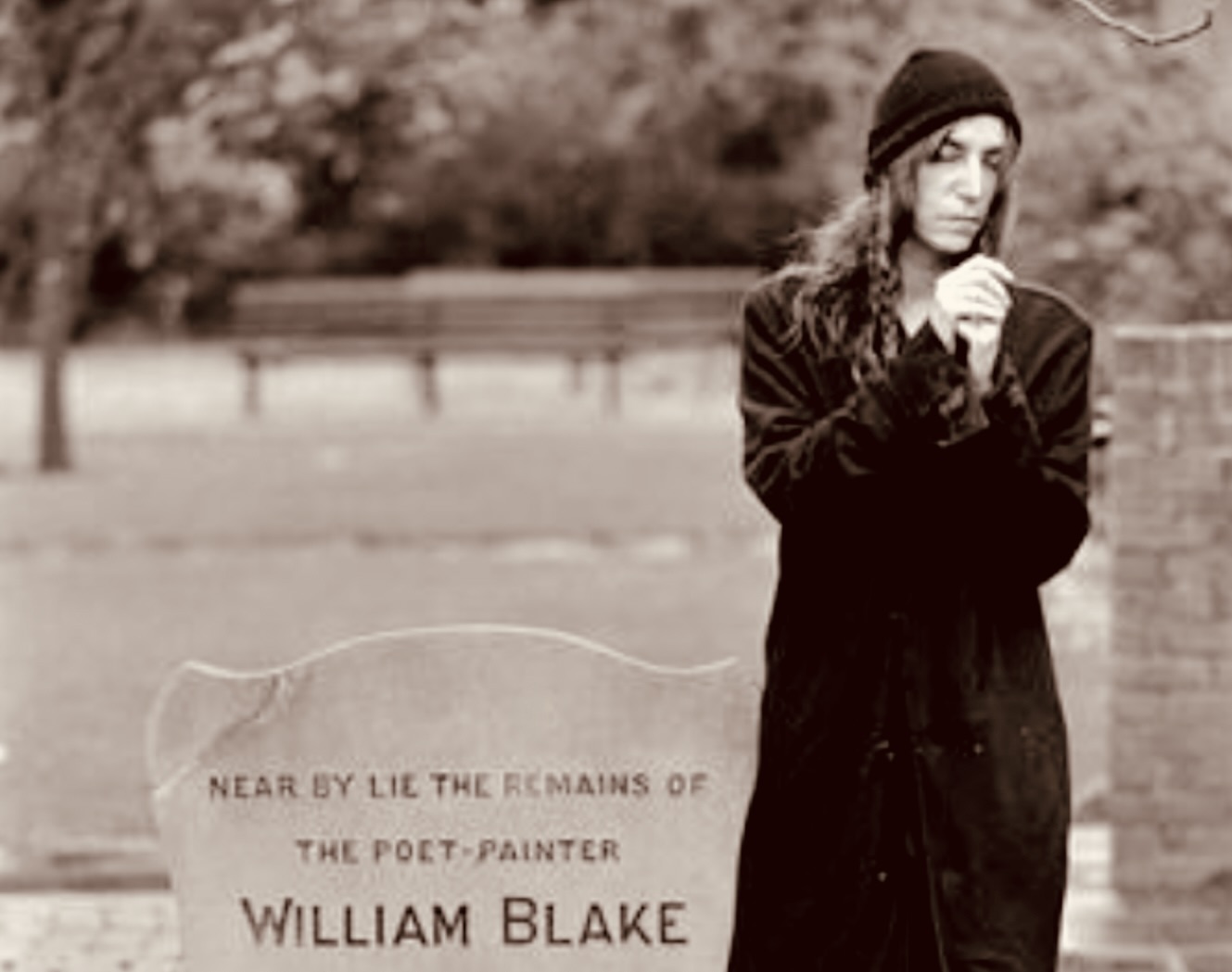

Through my life I have returned to him.

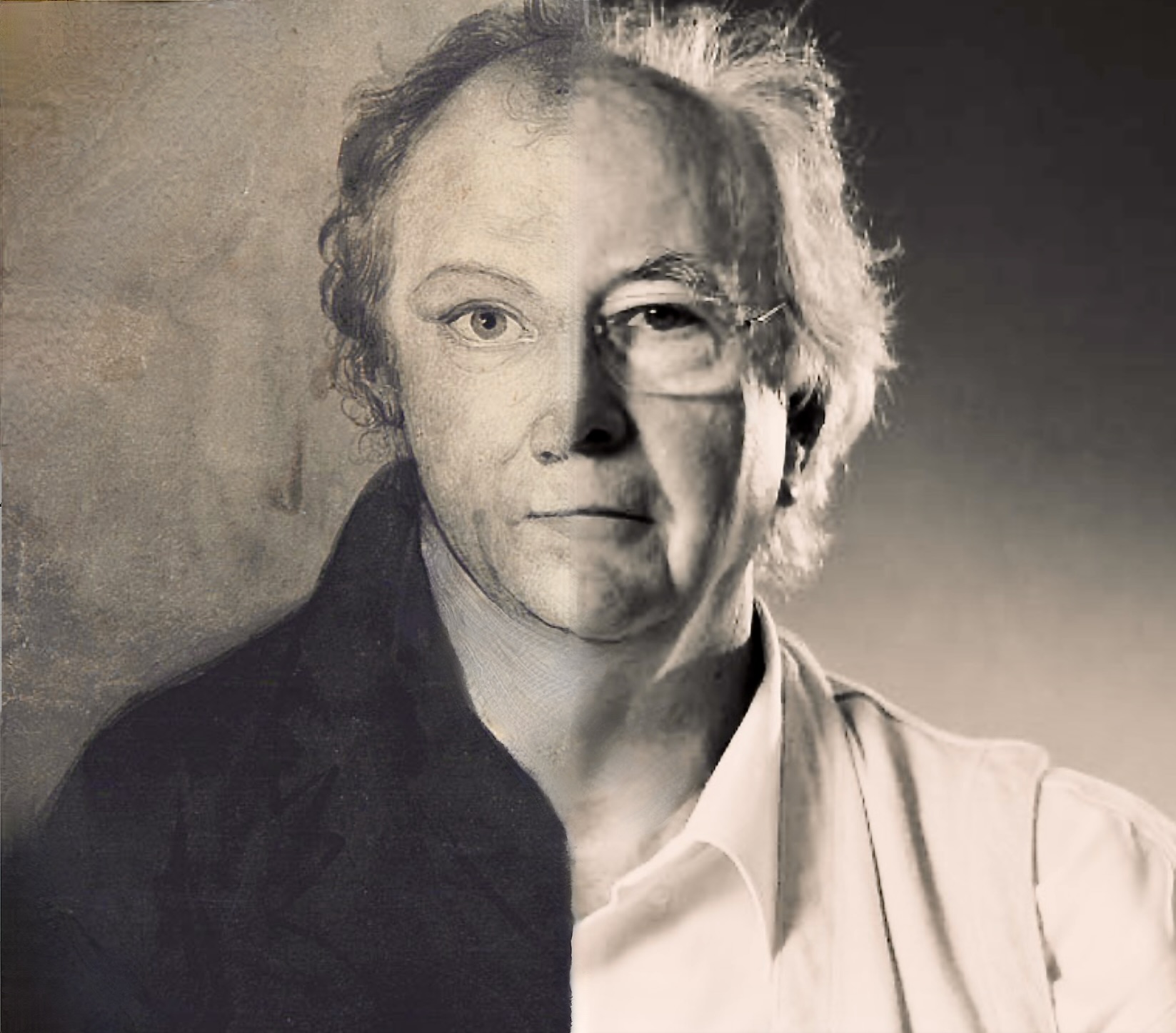

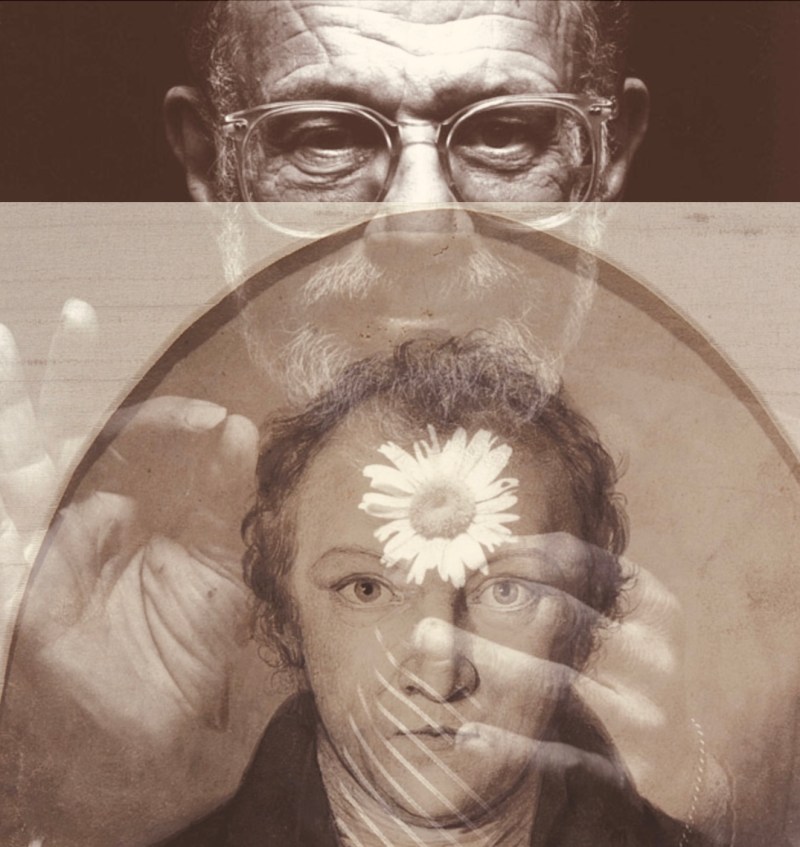

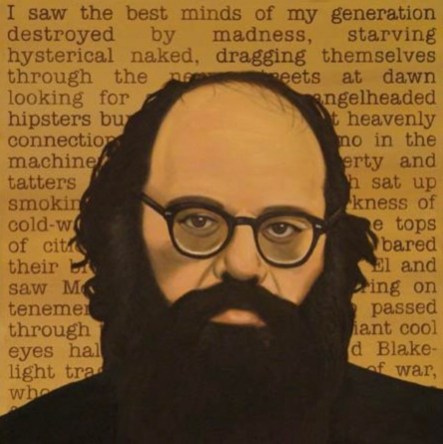

When Allen Ginsberg lay dying, I was among those who sat vigil by his bedside. I wandered into his library and randomly chose a book, a volume of Blake in blood-red binding. Each poem was deeply annotated in Allen’s hand, just as Blake had annotated Milton. I could imagine these prolific, complex men discoursing; the angels, mute, admiring.

William Blake felt that all men possessed visionary power. He cited from Numbers 11:29: “Would to God that all the Lord’s people were prophets’. He did not jealously guard his vision; he shared it through his work and called upon us to animate the creative spirit within us.

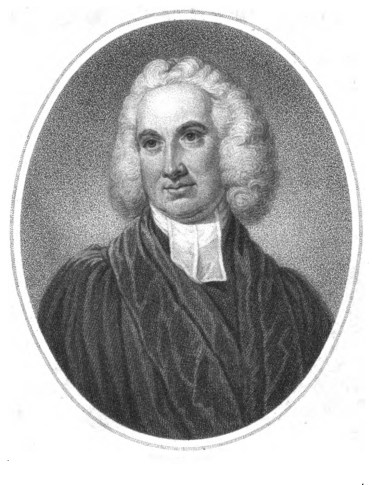

According to old Chinese belief, William Blake (1757– 1827) was cursed, since there is no question he lived in ‘interesting times’. Blake was a visionary English poet and artist. He was fascinated by apocalyptic biblical beliefs and prophecies, and worked elements of these even into artworks commissioned of him to illustrate the texts of other poets.

According to old Chinese belief, William Blake (1757– 1827) was cursed, since there is no question he lived in ‘interesting times’. Blake was a visionary English poet and artist. He was fascinated by apocalyptic biblical beliefs and prophecies, and worked elements of these even into artworks commissioned of him to illustrate the texts of other poets.