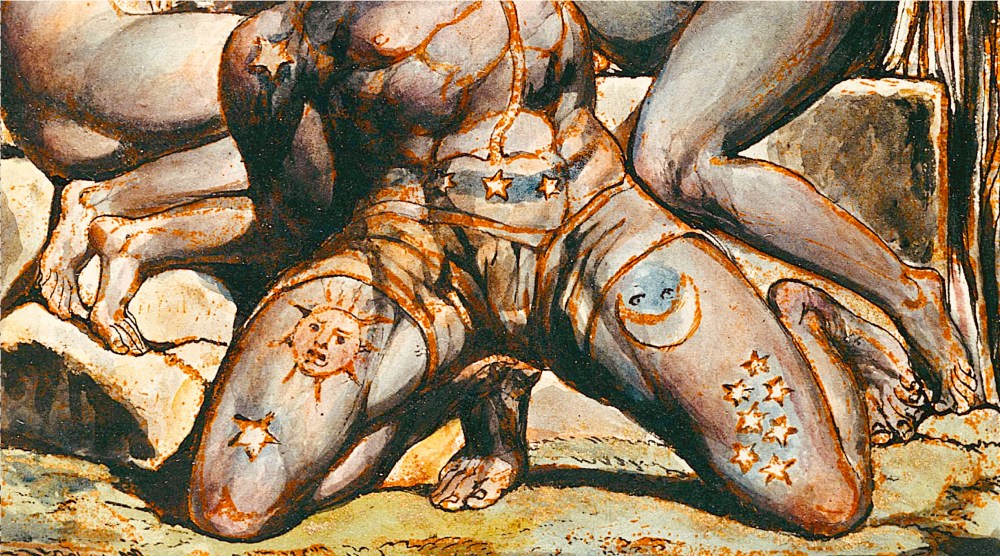

How to Enter the Kingdom of Heaven: William Blake and the Erotic Imagination

When I first Married you, I gave you all my whole Soul

I thought that you would love my loves & joy in my delights

Seeking for pleasures in my pleasures, O Daughter of Babylon

Then thou wast lovely, mild & gentle, now thou art terrible

In jealousy & unlovely in my sight, because thou hast cruelly

Cut off my loves in fury till I have no love left for thee.

Thy love depends on him thou lovest & on his dear loves

Depend thy pleasures which thou hast cut off by jealousy.

— Milton (1804-10), plate 33

In 1863 Alexander Gilchrist corrected the claim made by J.T. Smith, a friend of Blake, that the artist and “his beloved Kate” lived in “uninterrupted harmony”. Such harmony there really was; but it had not always been unruffled. There had been stormy times in years long past, when both were young; discord by no means trifling while it lasted. But with the cause (jealousy on her side, not wholly unprovoked), the strife had ceased also. Read More