Zodiacal Physiognomy: William Blake’s friendship with astrologer John Varley

Blake and Varley

Blake and Varley: Portrait of Blake by Thomas Phillips (1807), and portrait of Varley by John Linnell (1820)

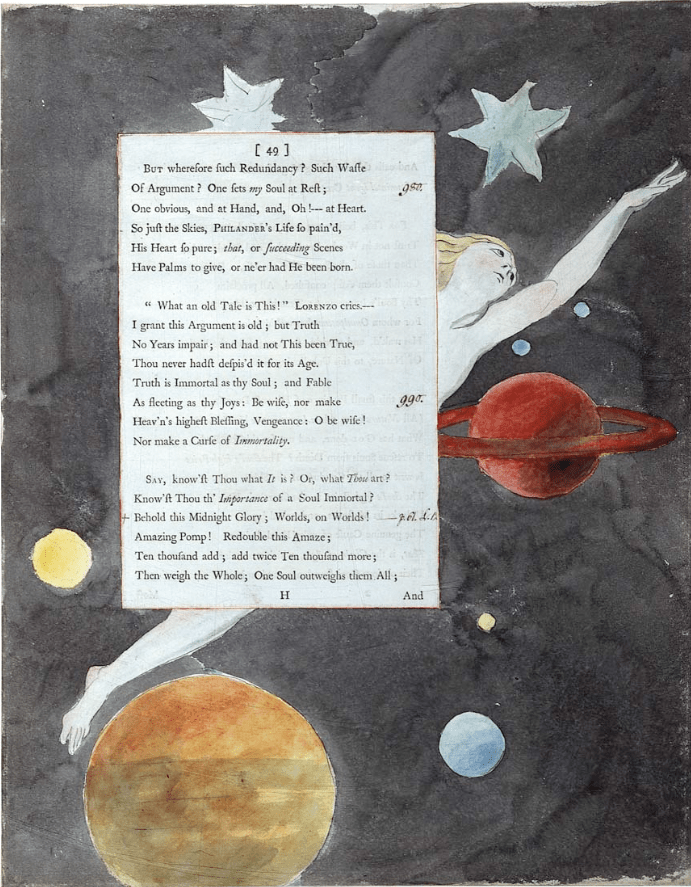

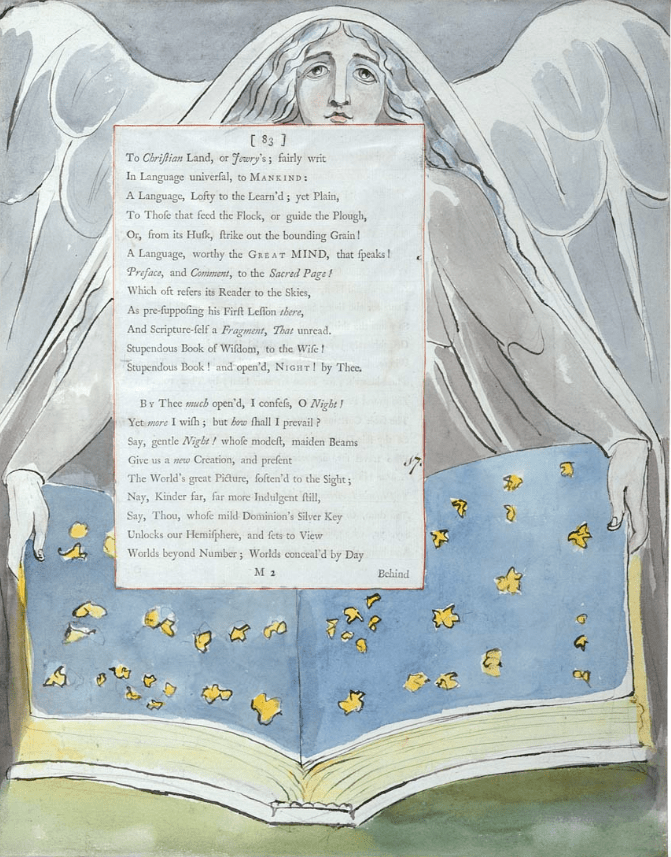

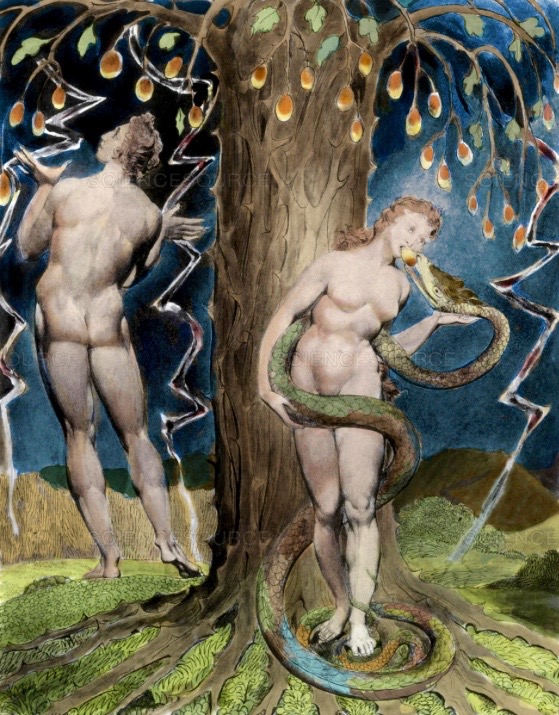

Blake’s friendship with the artist and astrologer John Varley (1778–1842) is one of the most unusual and intriguing of all Blake’s unusual and intriguing friendships. They first met in 1818, when they were living as near-neighbours in London, and it is Varley we have to thank for the remarkable series of drawings of ‘Visionary Heads’ that Blake made, in the company of Varley, over a number of late-night (or rather early morning) meetings – or ‘seances’ as some people called them – that they had, usually at Varley’s house, 10 Great Titchfield Street, off Oxford Street, which was near to Blake’s in South Molton Street. These drawings included the famous image of ‘The Ghost of The Flea’; it is a rather remarkable fact that this Ghost arose out of their discussions about astrology and the possible influence of the position of the planets on both our psychology and physiognomy. The Ghost (or Spiritual Form) of the Flea, apparently, denoted ‘Gemini’.

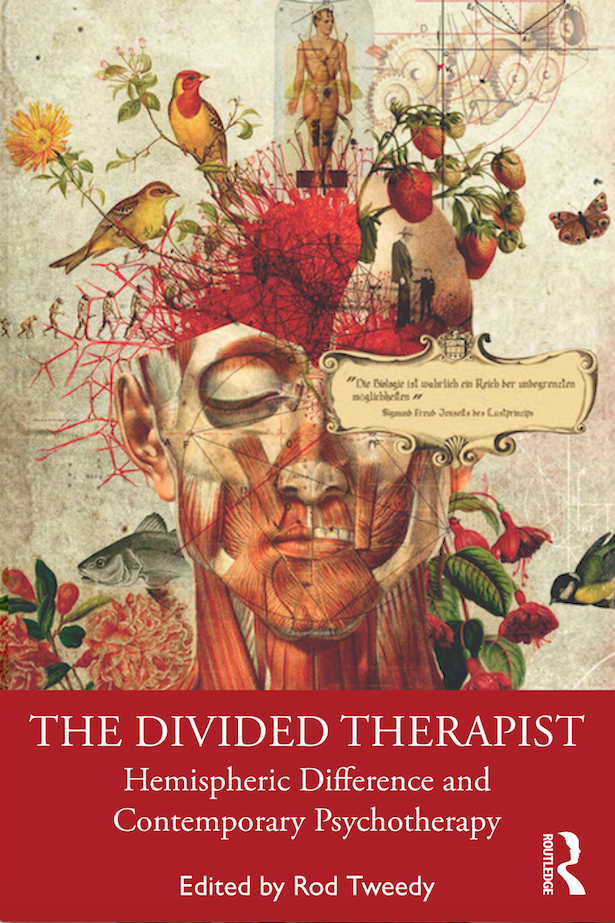

Blake’s drawings (including that of the Flea) were used by Varley for his 1828 book A Treatise on Zodiacal Physiognomy – the only time that Blake collaborated with someone else on the production of a book. And what an fascinating book it is: ‘Zodiacal Physiognomy’ is surely one of the most intriguing titles for a book ever. But what exactly was zodiacal physiognomy?

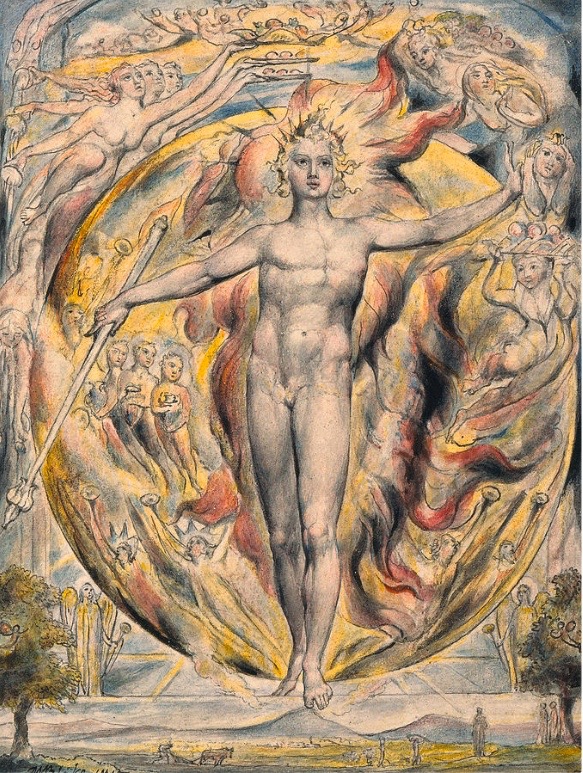

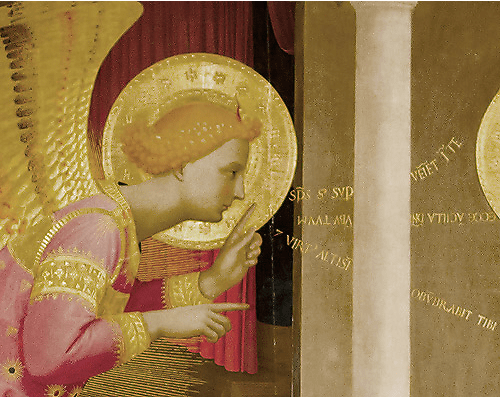

Blake’s art speaks in symbols. But what exactly are symbols? And why are all of the deepest ancient esoteric truths always communicated through symbol and image? Pike suggests that symbols are the most powerful way to mediate and convey a “truth” that lies beyond ordinary conscious, “rational” thought programmes and parameters: “The first learning in the world consisted chiefly in symbols. The wisdom of the Chaldæans, Phœnicians, Egyptians, Jews; of Zoroaster, Sanchoniathon, Pherecydes, Syrus, Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, of all the ancients, that is come to our hand, is symbolic. It was the mode, says Serranus on Plato’s Symposium, of the Ancient Philosophers, to represent truth by certain symbols and hidden images.”

Blake’s art speaks in symbols. But what exactly are symbols? And why are all of the deepest ancient esoteric truths always communicated through symbol and image? Pike suggests that symbols are the most powerful way to mediate and convey a “truth” that lies beyond ordinary conscious, “rational” thought programmes and parameters: “The first learning in the world consisted chiefly in symbols. The wisdom of the Chaldæans, Phœnicians, Egyptians, Jews; of Zoroaster, Sanchoniathon, Pherecydes, Syrus, Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, of all the ancients, that is come to our hand, is symbolic. It was the mode, says Serranus on Plato’s Symposium, of the Ancient Philosophers, to represent truth by certain symbols and hidden images.”