Blake’s Jerusalem as Visionary Theatre, by Susanne M. Sklar

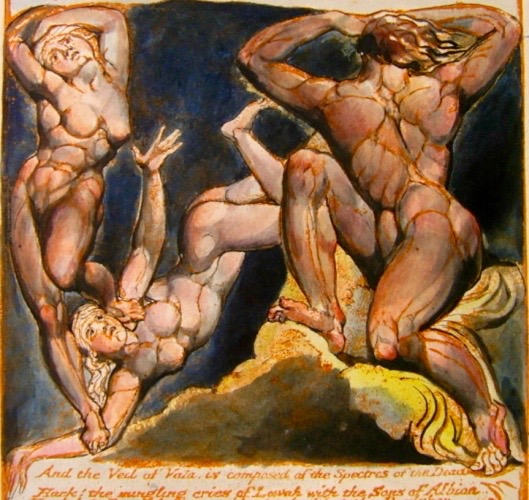

Entering the Divine Body, the Human Imagination

William Blake created Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion between 1804 and 1820. Since its conception this epic poem, compromised of one hundred illuminated plates divided into four chapters, has baffled many good readers. In 1811 Robert Southey thought it was “perfectly mad”; in 1978 W. J. T. Mitchell called it “some species of antiform” whose “narrative goes nowhere”; Robert Essick more recently wondered if “it is more than a curiosity shop with some treasures hidden amidst the clutter?” Many reasonable readers think the poem makes no sense.