Embrace what you Fear: Being with Blake

My Introduction to Blake

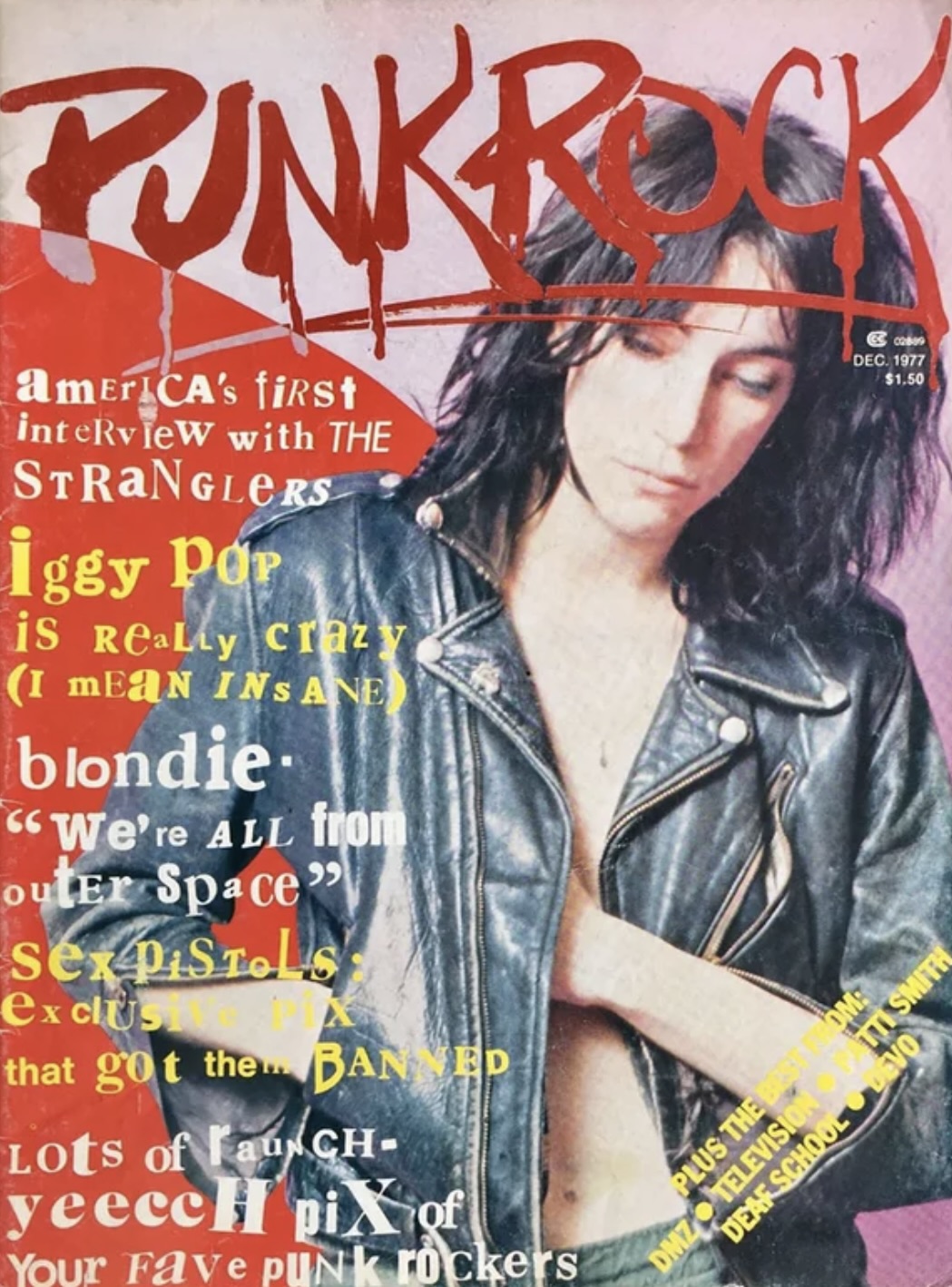

“I can’t imagine my childhood without him. His poems were my companions, my friends. I had pneumonia, I contracted TB, scarlet fever, every childhood disease. And my two favourite books were William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, and the children’s poems of Robert Louis Stevenson.” In 2007, to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Blake’s birth, Smith edited a selection of his verses simply titled Poems — “a bit of Blake, designed as a bedside companion or to accompany a walk in the countryside, to sit beneath a shady tree and discover a portal into his visionary and musical experience.”

My mother gave me Blake. In a church bazaar she found Songs of Innocence, a lovely 1927 edition faithful to the original. I spent long hours deciphering the calligraphy and contemplating the illustrations entwined with the text. I was fascinated by the possibility that one creates both word and image as did Blake, with copperplate, linen and rag, walnut oils, a simple pencil.

My father helped me comprehend this childless man who seemed to me the ultimate friend of children, who bemoaned their fate as chimney sweeps, labourers in the mills, berating the exploitation of their innocence and beauty.

Through my life I have returned to him.

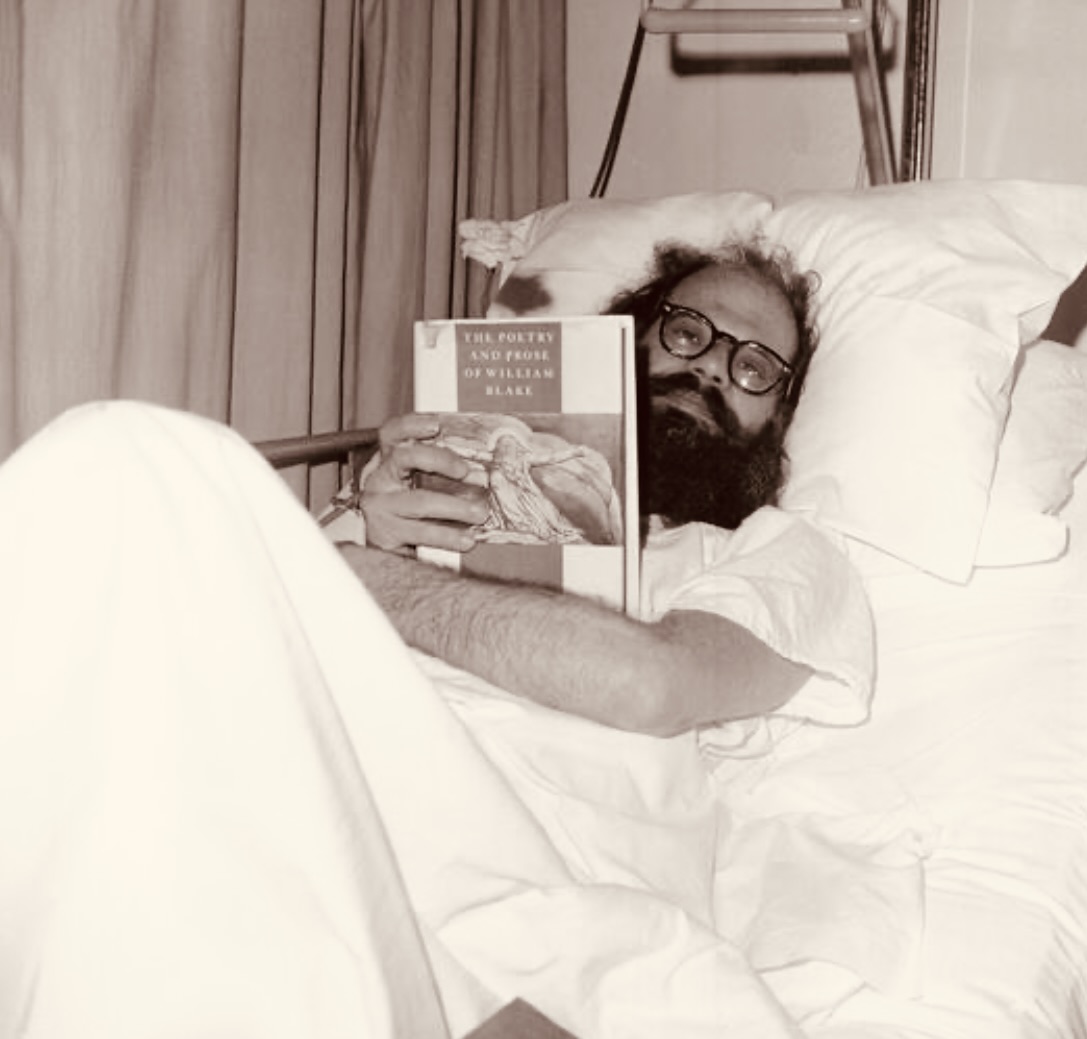

When Allen Ginsberg lay dying, I was among those who sat vigil by his bedside. I wandered into his library and randomly chose a book, a volume of Blake in blood-red binding. Each poem was deeply annotated in Allen’s hand, just as Blake had annotated Milton. I could imagine these prolific, complex men discoursing; the angels, mute, admiring.

William Blake felt that all men possessed visionary power. He cited from Numbers 11:29: “Would to God that all the Lord’s people were prophets’. He did not jealously guard his vision; he shared it through his work and called upon us to animate the creative spirit within us.

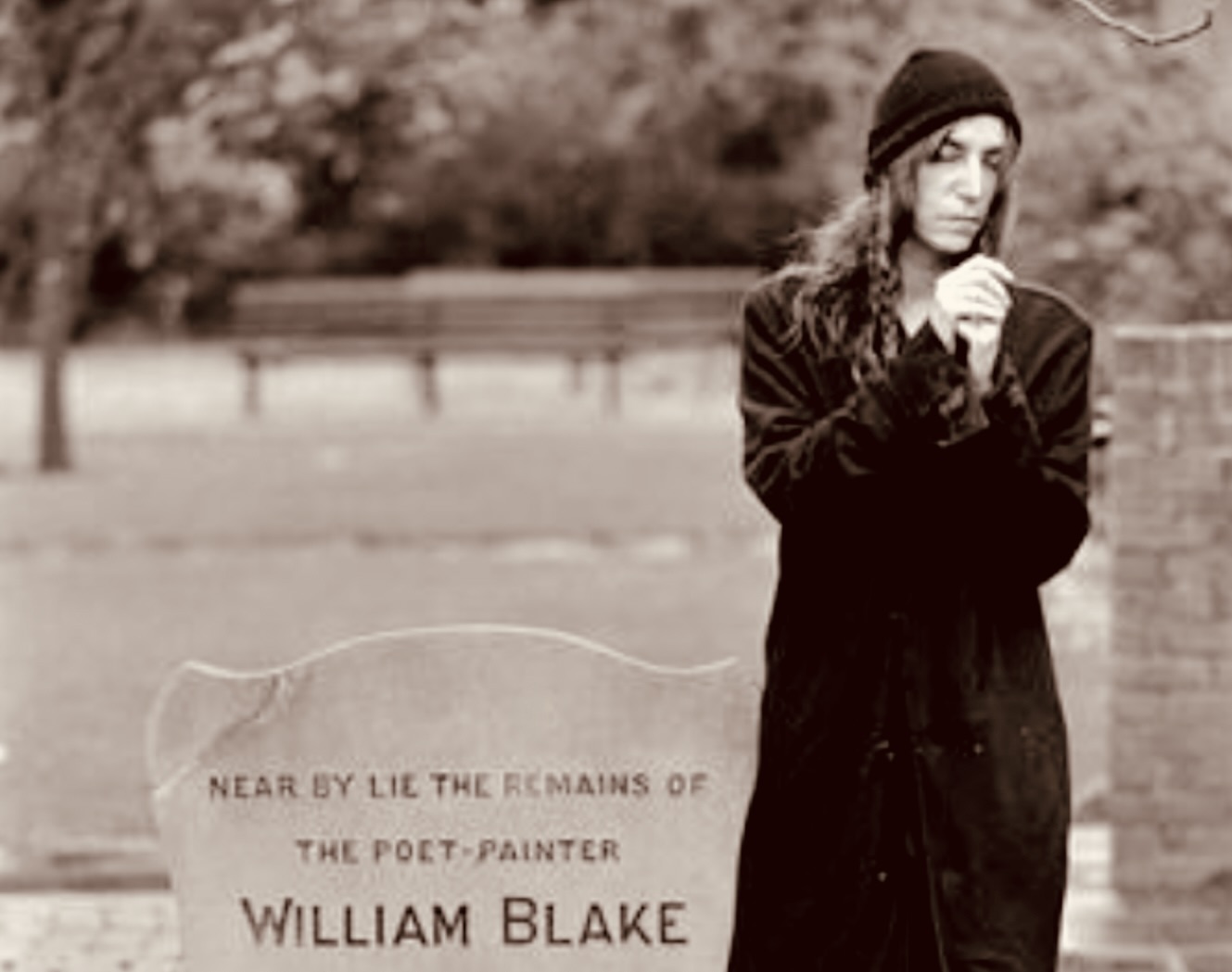

Allen Ginsberg with his beloved Blake (in hospital in 1968); above: Patti Smith with Carl Solomon, William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg in New York City, 1977.

‘I wrote my happy songs, every child a joy to hear’.

May we all listen as children as we enter his garden.

There is in his song something of the Appalachian, whose ballads immigrated from British soil. Threnody played with a dark fiddle. They remind me that when I was young I thought Blake was American. Many might claim him now.

Although much of his work seems impenetrable he never ceased in his desire to connect with the populace. He has succeeded in offering both. He has been the spiritual ancestor of generations of poets and alchemical detectives seeking their way through the labyrinth of inhuman knowledge even as schoolchildren recite his verses. His proverbs have become common parlance.

To take on Blake is not to be alone.

Walk with him. William Blake writes ‘all is holy’.

Never Let Go of Vision: In My Blakean Year

Patti Smith performing her song ‘My Blakean Year’ at The New York Public Library on April 29, 2010.

William Blake, in his lifetime a victim of the Industrial Revolution, was a great poet, a great song-writer, an activist , a philosopher, a visionary … and yet William Blake in his lifetime was never appreciated. He had no real success, he was often ridiculed, he died poverty-stricken, but he also died full of joy. He never let go of his vision, he never let go of that radiance, he never let go of the language of enthusiasm. So I try to remember now, when I feel sorry for myself, to give a little thought to William Blake.

In my Blakean year

I was so disposed

Toward a mission yet unclear

Advancing pole by pole

Fortune breathed into my ear

Mouthed a simple ode

One road is paved in gold

One road is just a roadIn my Blakean year

Such a woeful schism

The pain of our existence

Was not as I envisioned

Boots that trudged from track to track

Worn down to the sole

One road is paved in gold

One road is just a roadBoots that tread from track to track

Worn down to the sole

One road is paved in gold

One road is just a roadIn my Blakean year

Temptation but a hiss

Just a shallow spear

Robed in cowardiceBrace yourself for bitter flack

For a life sublime

A labyrinth of riches

Never shall unwind

The threads that bind the pilgrim’s sack

Are stitched into the Blakean back

So throw off your stupid cloak

Embrace all that you fear

For joy will conquer all despair

In my Blakean year

“His life was a testament of faith over strife.He suffered poverty, humiliation and misunderstanding, yet he continued to do his work and maintained a lifelong belief in his vision”- Patti Smith on William Blake

William Blake never let go of the loom’s golden skein. The celestial source stayed bright within him, the casts of heaven moving freely in his sightline. He was the loom’s loom, spinning the fibre of revelation; offering songs of social injustice, the sexual potency of nature, and the blessedness of the lamb. The multiple aspects of woven love.

His angels entreat, drawing him through the natural aspects of their kingdom into the womb of prophecy. He dips his ladle into the spring of inspiration, the flux of creation.

A rough-hewn seer who never tasted but English air, who loved Michelangelo yet never saw Rome.

Laboring over his work in sleeves ink-stained, he transfigures London into the new Jerusalem. His crushed hat and threadbare coat seem to pulsate as he wends his way through the grimy clatter. He heads past dark factories where pubescent girls with hair of matted gold offer themselves in the shadows for a bit of bread. Later, through his swift fingers, they transform as the virgins of his glad day, languishing in the bath of absolution, readied to accept the seed of God.

He is a messenger and a god himself. Deliverer, receptacle and fount.

Blake and Today

“I often feel like William Blake in the middle of the Industrial Revolution”

I’m aware that at this time in my life, some of my work might not be relevant to the aesthetic shift in terms of melding creative and political ideas with our current technology. I often feel like William Blake in the middle of the Industrial Revolution. But, like Blake, I just do my thing. I don’t care if the work that I do might have obsolete edges, I do it anyway because it may eventually be needed. Maybe as a stepping stone to help people find their way to where they are.

But I wrote ‘My Blakean Year,’ again, because I was in a difficult time, and I felt—I hate to say it, but I felt like sorry for myself. And it was like another thing where this—I was sitting—I was just sitting in my room, and then I thought of William Blake.

You know, I felt like very unappreciated or something—I don’t know why. But I was thinking of William Blake, who was such a great artist, poet, printer, philosopher, activist, who died in poverty, was ridiculed in his time, who was almost forgotten. But in his lifetime—and also such a true visionary—he never let go of his visionary powers. He did his work, even thought the Industrial Revolution sort of wiped him out in terms of being a printer and a public artist. He got in a lot of trouble because of his political views. He championed women, and he was against children, women and children labouring. They didn’t have labour laws in place at that time. And he did his work, and he did it unapologetically. And he also did it without remorse or feeling sorry for himself, and just accepted, you know, his particular lot and just kept working.

Anyway, sorry that took so long to say, but basically the lesson is that people—other people in the world, I know, really suffer strife. They really know strife. They have to deal with war. They have to deal with disease, poverty, displacement. When I look at everyone around me, I have to really counsel and scold myself when I feel, you know, a little sorry for myself. And so, this song is to remind me of that, but also remember to—when you take on the mantle of an artist or an activist, you know that you’re going to have a lot of derision. So, you have to meet that derision almost with pride. You know, you have to be a happy warrior.

Fearful Symmetry: My Tyger

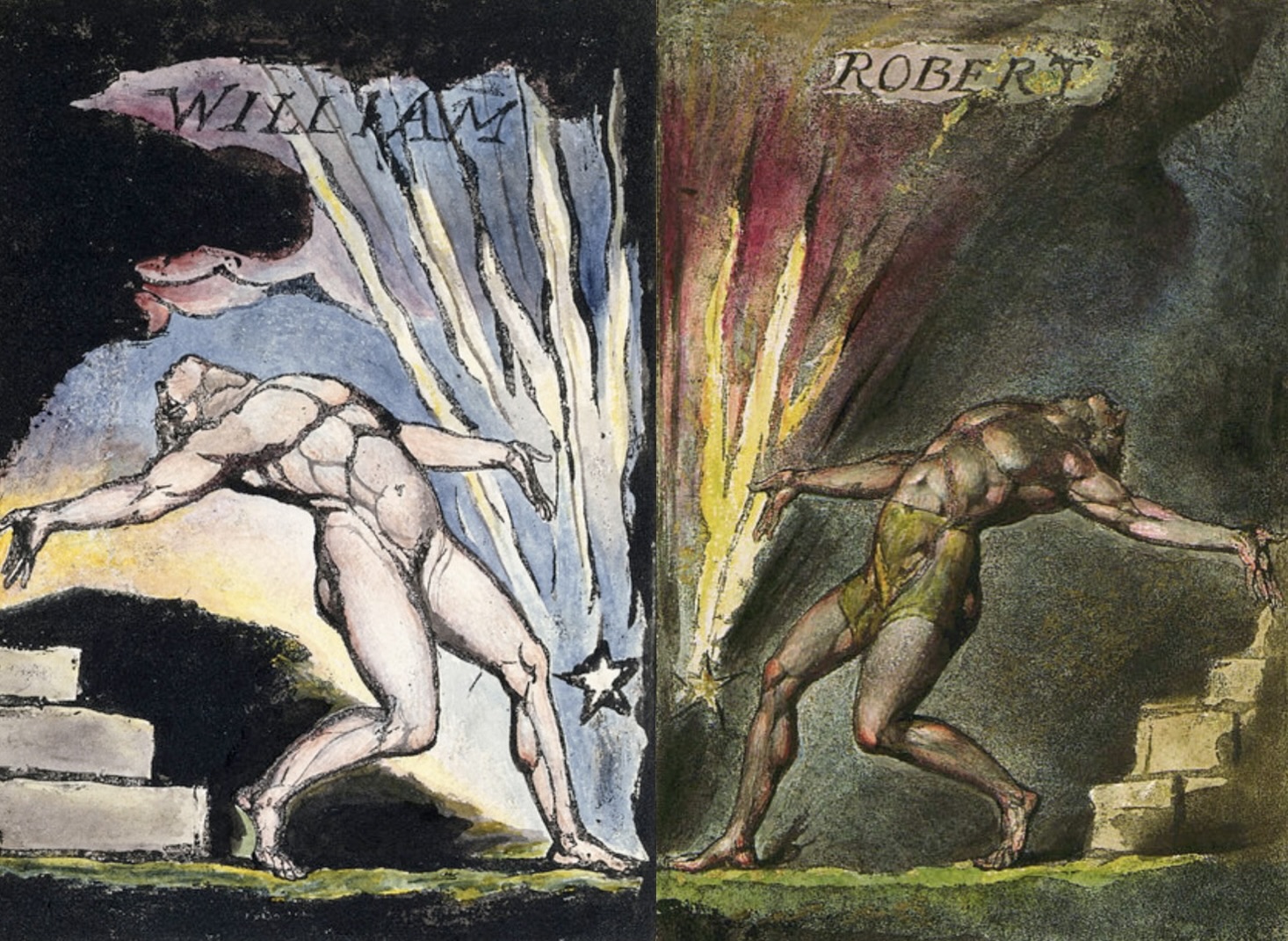

William Blake, the great poet, activist, printer, painter, had a younger brother named Robert, and he adored his brother and he was training his brother as a printer, and his brother was also a gifted draftsman. Robert died at a very young age, and William was devastated at the loss of Robert. Robert had a humble black sketchbook and William, for the rest of his life, kept it by his bed, and he wrote some of his most important and some of his most beautiful poems in this little notebook.

It belongs to the British Museum, and they showed it at the Met, and they told me if I came the day they were packing to send it back to London, if I came at 8 o’clock in the morning I could look at it. And I think they thought because I sing rock and roll that I would never get up that early, but I reported and they let me look at it, and hold it, and they even left me alone with it in a room.

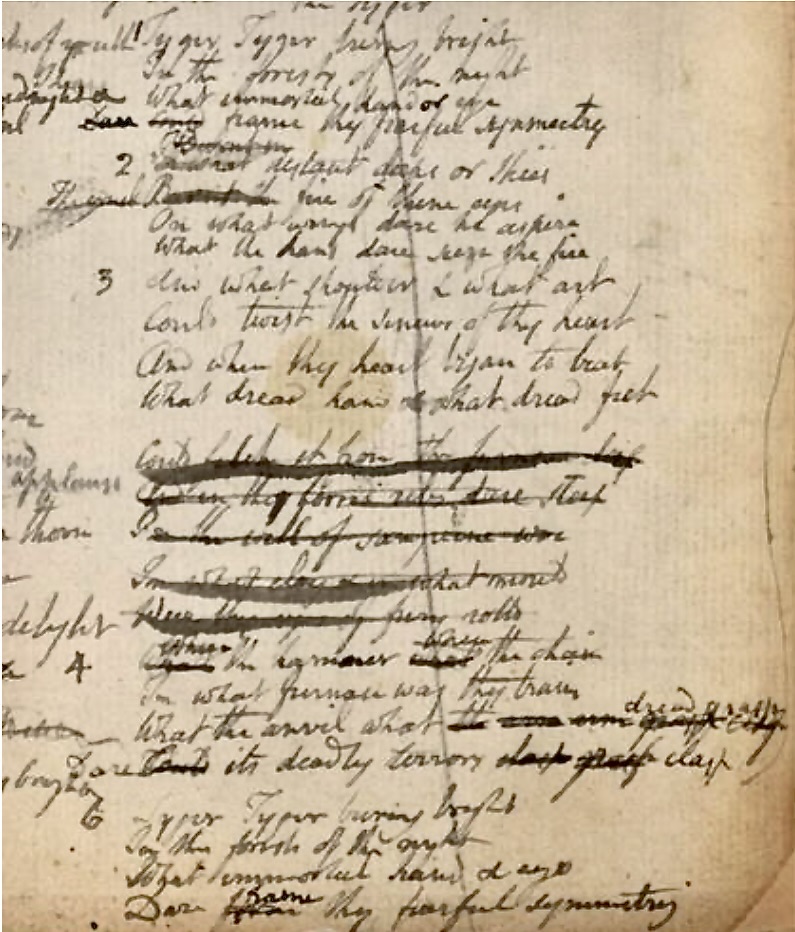

And I found in that book the original manuscript to this little poem.

(She sings:)

‘The Tyger’ by William Blake, first draft (Notebook 25)

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!When the stars threw down their spears

And water’d heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

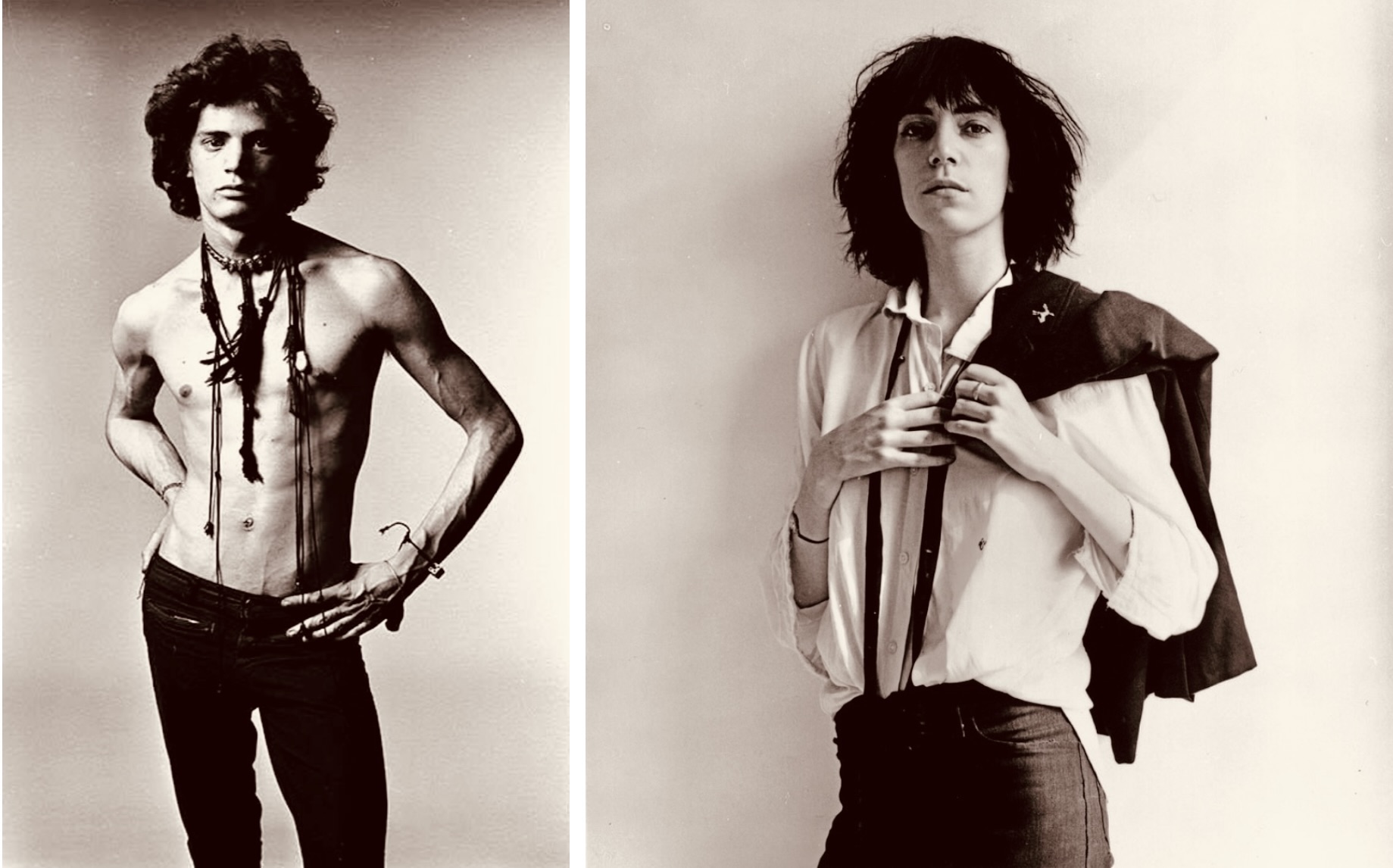

I’ve found a lot of fearful symmetry in my life. I think that, for me, the most fearful piece of symmetry, for instance—it’s even hard to talk about. My husband died in November of 1994 [Fred “Sonic” Smith, an American guitarist and member of the rock band MC5, who died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 44], and my brother [Todd Smith, who was also her road manager], who really expressed that he would help me raise my children, comforted my children, and who I deeply counted on, died suddenly from a faulty heart valve a month later—November 4th and December 4th. That was a bit of fearful symmetry. My husband died on Robert Mapplethorpe’s birthday [November 4th], which was a bit of fearful symmetry. Robert died on my husband and my anniversary. These things, they happen to everyone, but you look at them and gasp, because they have a certain kind of perfection, but that perfection is just bleeding sorrow. So, that, for me, is what a fearful symmetry is.

The fearful symmetries of life. Both Patti Smith and William Blake were devastated by the loss of someone they were devoted to in their lives: both were named Robert (Robert Blake, Robert Mapplethorpe).

Patti Smith is a writer, artist and performer. Her seminal album Horses was followed by ten releases, including Radio Ethiopia, Easter, Dream of Life, Gone Again, Trampin’ and, most recently, Twelve. Her artwork was first exhibited at Gotham Book Mart in 1973, and she has been associated with the Robert Miller Gallery since 1978.

Her books include Witt, Babel, Woolgathering, The Coral Sea and Complete Lyrics. In 2005 she received the Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Patti Smith lives in New York City and is the mother of two children, Jackson and Jesse.