Babylon, Nature-worship, and the Sleep of Albion

‘Awake! awake O sleeper of the land of shadows, wake! expand!’

As Kathleen Raine has noted, “the sleep of Albion is in a word the materialist mentality of the modern West.” However, this “materialist mentality”, for Blake, denotes not only the belief in the Newtonian universe of orthodox Science, which many are now questioning, but also the belief in “Nature” itself. For Blake, the “Creation” – the emergence of an apparently objective, natural, and material world – and Albion’s fall into “Sleep” were one and the same event.

objectification is the start of the splitting process

Northrop Frye similarly observes that this Sleep or “Fall into Division” signifies “Albion’s relapse from active creative energy to passivity. This passivity takes the form of wonder or awe at the world he has created, which in eternity he sees as a woman. The Fall thus begins in Beulah, the divine garden identified with Eden in Genesis. Once he takes the fatal step of thinking the object-world independent of him, Albion sinks into a sleep symbolizing the passivity of his mind, and his creation separates and becomes the ‘female will’ or Mother Nature, the remote and inaccessible universe of tantalizing Mystery we now see” (Frye). This “sinking” (of the psyche), in Blake’s mythology, correlates to the submersion of “Atlantis” in earlier mythologies, the overwhelming of our imaginative senses by “the Sea of Time & Space”.

Albion’s universe is forcibly extracted and separated from him as Vala, Rahab and Tirzah combine to draw out the living fibres, seen as a cord, from his body

It was in and through this form of unconsciousness that “Natural Religion” and in particular “Druidism” also emerged, as a way of both engaging with and controlling what now appeared to be a separate, natural world. This leads to one of the most challenging and provocative aspects of Blake’s work, which is the idea that anyone who believes in “Nature” is basically still asleep – that pantheism is more of a sign of somnambulism than spirituality. It is a projection outwards of the “Divine Vision”, and we eventually become enslaved to the projection. “Whoever believes in Nature,” Blake once remarked, “disbelieves in God” (Gilchrist on Blake).

It is not merely that those who believe in the mental construct “Nature” are pantheistic rather than theistic, for Blake: but rather that this “mind-forged” concept of Nature is itself a delusion, a mistaken or fake form of spirituality, and that those who assert their belief in this delusion are largely unaware of the basis of its naturalising programme within the brain, and its deep roots in Newtonian materialism.

‘Of the Sleep of Ulro’. The hooded woman in the center is Vala, keeping Albion down

The first five words of Jerusalem sum up this naturalising stance: “Of the Sleep of Ulro” (Jerusalem 1:1). Blake was clearly well-aware of Nature-worship: he was living in the age of Enlightenment pantheism – of Rousseau and Wordsworth – and it’s no surprise to learn that, for all of his deep admiration for Wordsworth’s craft as a poet, reading his more pantheistic passages about “how exquisitely the individual Mind to the external World is fitted” and how exquisitely “The external World is fitted to the Mind” could make him feel actually physically ill (Gilchrist). As Crabb Robinson notes, recording a conversation he himself had with Blake: “His delight in Wordsworth’s poetry was intense. Nor did it seem less, notwithstanding the reproaches he continually cast on his worship of nature. ‘For whoever believes in Nature,’ said Blake, ‘disbelieves in God; for Nature is the work of the devil.’ ” Crabb Robinson actually challenged him on this, mentioning the description of the “Creation” at the start of the Book of Genesis as being the work of God – “But I gained nothing by this; for I was triumphantly told that this God was not Jehovah, but the Elohim; and the doctrine of the Gnostics was repeated with sufficient consistency to silence one so unlearned as myself.”

Elohim creating Adam: Blake’s take on the Book of Genesis, showing man splitting and the creation of the ‘Nature’ program

What we glimpse here in Blake is a formidable and consistent approach to “Nature” and in particular to the “worship of Nature” – and one, moreover, that is typically Blakean in being able to take delight in the imaginative power of a poet like Wordsworth – recognising that his craft derives from his inner mind, his poetical faculty, not from the “external” World – whilst still being able to recognise the fundamental contradiction in his verse: “I see in Wordsworth the natural man rising up against the spiritual man continually; and then he is no poet, but a heathen philosopher, at enmity with all true poetry or inspiration.”

Re-awakening the Mind

The awakening of Albion, for Blake, therefore corresponds to the re-awakening of this faculty itself, within us. By the same token, Albion’s continuing “sleep” alludes to this misperception of the relationship between inner and outer. This might be summed up by the popular misconception that ‘we are part of Nature’, which many people today would perhaps see as a rational and “natural” thing to believe. For Blake, this error goes to the heart of the problem with both pantheism and deism, and indeed the rationalism and naturalism on which they’re based, and he deftly signalled the shift that needs to occur within our brains – within our perceptions of reality – in his startling observation that Man is not part of Nature – rather, Nature is part of Man, “for that calld Body is a portion of Soul discernd by the five Senses” (MHH, plate 4), and until we properly understand this distinction, and its implications for our sense of our relationship to reality, our imaginative divinity will never be properly liberated or realised.

“For man has closed himself up till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern”: when the present body of man was achieved, the universe necessarily appeared to that body in its present shape

Thus, when Man fell – when Albion fell asleep – his senses turned outward: “they behold/What is within now seen without” (FZ ii.25: 22-23), and Nature appeared to be separate from Man. That is the delusion: “in your own Bosom you bear your Heaven/And Earth, & all you behold; tho it appears Without it is Within” (Jerusalem 71:17).

This is not a marginal concern for Blake: it is the central, driving theme of his work. “I rest not from my great task!”, he declares in the very opening chapter of Jerusalem: “To open the Eternal Worlds, to open the immortal Eyes/Of Man inwards into the Worlds of Thought: into Eternity/Ever expanding in the Bosom of God. the Human Imagination” (Jerusalem 5: 17-20). Those who look to Nature, look inside out – they close this spiritual sight and come to depend, to hang on, the natural world, as the source of vision and reality, whereas it is but the transient reflection.

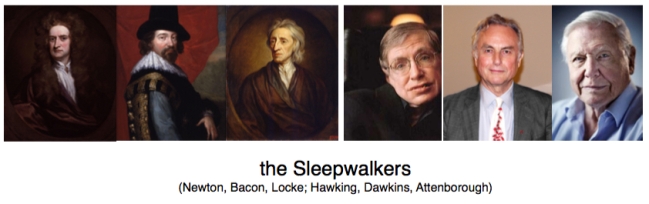

“Nature is part of man”, notes S. Foster Damon, “- that part which, including the physical body, is perceived by the senses. According to Jewish tradition man originally ‘containd in his mighty limbs all things in Heaven & Earth. But now the Starry Heavens are fled from the mighty limbs of Albion’ ” (Jer 27; in Damon, A Blake Dictionary). But now the Starry Heavens are fled from the mighty limbs of Albion: and one of the signs of this alienation or dismemberment of inner and outer, paradoxically, is the very pantheistic worship of those “starry heavens” – from Newton and Galileo to Stephen Hawking and Brian Cox – the vast, inhuman cycles of rocks in the void.

The Little Boy Lost in Space

Universe, universe, where are you goingO do not spin so fast.Transmit, universe, to your little accidentOr else I shall be rational.

The screens were blank, no signal was thereThe space boy wept with H2O.The volcanoes were deep and the boy did weepAnd away the spirit flew.

One of the things that surprised me the most in researching my book on Blake and the ‘left hemisphere’ was learning that for Blake the “stars” are not symbols of some vast, inspiring, imaginative realm – as our post-Sumerian (astronomical) cultures like to think – but are the symbols and typography of Urizen: the deep rationalising, ordering, abstracting mills and mechanisms of the human brain, which it then sees projected on the night sky in tremendous forms and spontaneously identifies with – and then deifies.

“Starry Mills”: the vast repetitive cycles that the autistic brain is emotionally obsessed with

As Damon acutely notes, “the Stars symbolise Reason. They are the visible machinery of the astronomical universe. ‘In that dread night when Urizen call’d the stars round his feet,’ the whole universe was disorganised and took its present form.” Blake repeatedly alludes to the “starry wheels” of Albion’s Sons in order to represent the materialistic, mechanistic – indeed rather autistic – appeal of the thought processes behind them – the “Starry Hosts”, or “Starry Mills of Satan” (Milton 4:2), where ‘Satan” is simply Blake’s term for the rationalising “Selfhood” (“the Great Selfhood, Satan”; Jerusalem 29:17-18).

These “Mills” therefore denote the mechanical, self-enclosed systems of thought that for Blake characterised and constituted the underling mental processes of modernity, and which he believed lay behind both the God of orthodox Christianity and the methodology of post-Newtonian science and the Nature-worship to which it gave rise. They are the same “dark Satanic mills” that many people often mistakenly believe allude to actual mills and industrial factories. Instead, they denote the various mental “mills” that preceded and were incarnated in them – the belief in materialism, the belief in rational “Nature”, the belief in orthodox Christianity.

Reason and Nature

This belief in “Nature” and the independent reality of a “natural” world is, for Blake, a necessary consequence of the rationalistic and materialistic philosophy inaugurated by Enlightenment figures such as Bacon, Locke and Newton. Their systems of thought transmuted ‘Being’ (infinite, transcendent, spiritual, intersubjective) into ‘Nature’ (finite, representational, literal, external). As Northrop Frye explains, “the two great pillars of Deism, reason and nature, incarnate in Voltaire and Rousseau. It was only in the age of reason that Rousseau could have thought up his conception of nature.” It is significant in this respect that “Nature” only emerged, as it is understand today, in the seventeenth-century: belief in “Nature” is as much a by-product of the Industrial Revolution as industrial effluent.

It is important to recognise that in this sense the concept of “Nature” is not itself “natural”: it is what Timothy Morton terms an “arbitrary rhetorical construct” that “wavers in between the divine and the material. Far from being something ‘natural’ itself, nature hovers over things like a ghost.” This “hovering” aspect to the word is why in some cultures “Nature” is referred to as “Maya” or “Māyā”, a delusory veil woven over our perception of reality to ensnare us to it – what Blake terms “Vala”, or what the Book of Revelations sometimes refers to as “Mystery”.

Vala trapping Albion in her nets and roots

When pressed, it is often difficult for those who profess to believe in this empty signifier to explain what it actually refers to. It is hard, for example, to reconcile many people’s apparently benign view of “Nature” with Darwinian evolution. Many pantheists look to David Attenborough as a sort of apostle for their way of looking at the world with these naturalistic lenses. But Attenborough himself defines the agency of ‘Nature” in ways that might shock the passive viewers of his “natural history” programmes: when asked to provide a summary of Nature’s God, this is his response: “I always reply by saying that I think of a little child in east Africa with a worm burrowing through his eyeball. The worm cannot live in any other way, except by burrowing through eyeballs” (interview, cited in The Guardian).

The Blind Worm-maker: Nature’s God

This is what lies at the core of “Nature” worship, behind all the seductive veils of trees and fluffy clouds, that seem “without” us, and which seeks to convince us that we are part of it, rather than it being part of us – a small spectrum of existence, and merely that which can be observed through our five senses. It is also why Blake is so wary of it: he saw that behind the progressive rhetoric of eighteenth-century pantheism and rationalising Rousseau-perception the same alienated and self-contemptuous approaches to reality remained. It is based on an approach that, as Minna Doskow notes in her penetrating study of the poem, “reduces the Human Form Divine to a worm” (Jerusalem 27: 53-55, 29: 5-6; Doskow, William Blake’s Jerusalem).

Unpacking Nature-worship: The Fly

Some of these approaches also appear, and are scrutinised, in Blake’s deceptively simple poem The Fly, which seems on the surface to be a progressive, eighteenth-century, empathic view of Nature: an expression of regret at the narrator having thoughtlessly brushed away the life of a small fly.

Some of these approaches also appear, and are scrutinised, in Blake’s deceptively simple poem The Fly, which seems on the surface to be a progressive, eighteenth-century, empathic view of Nature: an expression of regret at the narrator having thoughtlessly brushed away the life of a small fly.

Am not I

A fly like thee?Or art not thou

A man like me?

For I dance

And drink & sing;

Till some blind handShall brush my wing.

What actually underlies this sentiment though, as Morton persuasively suggests, is indifference. It is a song of ‘Experience’, not of Innocence: the experience of a progressive eighteenth-century pantheist intellectual.

Like many supporters of Darwinism later, the narrator believes he has come to a modern, enlightened view of things. But Blake in this poem takes this notion out for a spin, and unpacks the uneasy attitude towards existence – his own mortality, as well as that of the fly – which underwrites it. The implication of the poem is that we’re all totally equal. Morton translates its core message as: “You’re totally equal to a fly. The fly is just as important – or rather just as unimportant as you. So don’t worry. In fact don’t give a shit.” (Morton).

Like many supporters of Darwinism later, the narrator believes he has come to a modern, enlightened view of things. But Blake in this poem takes this notion out for a spin, and unpacks the uneasy attitude towards existence – his own mortality, as well as that of the fly – which underwrites it. The implication of the poem is that we’re all totally equal. Morton translates its core message as: “You’re totally equal to a fly. The fly is just as important – or rather just as unimportant as you. So don’t worry. In fact don’t give a shit.” (Morton).

What the fly’s death signifies is the meaningless at the heart of this apparently sentimental naturalism: do you want to live in a universe where you are a replaceable component? “Some blind hand” is a deft allusion both to Paley’s “blind watchmaker” universe, in which transcendence has been removed, and also to Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” of the market. Belief in “Nature” is the product of both: the bastard child of the underlying thought-processes of alienated and indifferent capitalism and of the materialising and mechanising programmes that for many people constitute “reality” in post-Enlightenment societies.

What the fly’s death signifies is the meaningless at the heart of this apparently sentimental naturalism: do you want to live in a universe where you are a replaceable component? “Some blind hand” is a deft allusion both to Paley’s “blind watchmaker” universe, in which transcendence has been removed, and also to Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” of the market. Belief in “Nature” is the product of both: the bastard child of the underlying thought-processes of alienated and indifferent capitalism and of the materialising and mechanising programmes that for many people constitute “reality” in post-Enlightenment societies.

Blake’s poem reveals that “Nature” is in fact a huge recycling bin: we’re born into it, die into it, our human life is relatively meaningless and absurd, and our belief in the divinity of our own humanity is thereby constantly “exchanged” in this nefarious transaction, under the rubric of enlightened post-Christian paganism. Blake would be appalled that England has become a nation of recycling pagans; just as recycling pagans should equally be appalled at Blake’s depiction of their belief system as the continuing unconscious and unthinking worship of Babylon: “the Goddess Nature/Mystery Babylon the Great” (Jerusalem 93: 24-25).

Anxious Urban Children: Psychoanalysing the post-industrial belief in ‘Nature’

Vala (upper left) pushing her daughter Jerusalem down with her feet, while striking a seductive pose to attract Albion (right)

What underlies this deification of Nature ultimately, for Blake, is a form of self-contempt or “despair” – which also perhaps explains why so many modern humans believe so little in our importance, or in the value of humanity, or in the life of other humans, or in our central role in the evolution of consciousness – and the real reason why we fail to acknowledge, or defend, our own divinity.

And this “exchange” – giving up belief in the divinity of Humanity and the human imagination in return for a certain form of material Power (or rather, promise of Power) – is for Blake the central act of “sacrifice” that Blake sees within all Druidic systems. Thus, in return for the “pseudospeciation” of humanity (reduced to animal, to machine, to cog, to “part”) – which is the underlying basis of the “bargain” or exchange – the Urizenic ‘left hemisphere’ is granted temporary power, or temporary temporal power, one might say, to continue this Faustian metaphor.

Power, in the pagan cults to which Blake refers, is represented by two main symbols: Stones (or stone circles), and the Sun and Stars. Those humans who are drawn to these symbols participate in this pathology, mistaking the true divinity in the universe, for the “other God”, as Blake refers to him, the Elohim of the Oaks of Albion:

In awful pomp & gold, in all the precious unhewn stones of Eden

They build a stupendous Building on the Plain of Salisbury; with chainsOf rocks round London Stone: of Reasonings: of unhewn Demonstrations

In labyrinthine arches. (Mighty Urizen the Architect.) thro which

The Heavens might revolve & Eternity be bound in their chain.

Labour unparallelld! a wondrous rocky World of cruel destiny

Rocks piled on rocks reaching the stars: stretching from pole to pole.

The Building is Natural Religion & its Altars Natural Morality

A building of eternal death: whose portions are eternal despair (Jer 66:1–9)

This druidical “Building” is therefore both within and without. As Damon adds, “the enormous rocks of these temples are their most impressive feature, and Blake constantly connects rocks and stones with the Druids, meaning that their religion is a petrifaction of human feelings” (Damon). This inner hardening or “petrifaction” correlates with the stones upon which all Urizenic civilisation is based: the worship of stones, as of stars (another sort of stone) is always an unconscious indicator of Urizenic presence and Urizenic control of the human brain in Blake’s work: “chains/Of rocks round London Stone: of Reasonings”.

This druidical “Building” is therefore both within and without. As Damon adds, “the enormous rocks of these temples are their most impressive feature, and Blake constantly connects rocks and stones with the Druids, meaning that their religion is a petrifaction of human feelings” (Damon). This inner hardening or “petrifaction” correlates with the stones upon which all Urizenic civilisation is based: the worship of stones, as of stars (another sort of stone) is always an unconscious indicator of Urizenic presence and Urizenic control of the human brain in Blake’s work: “chains/Of rocks round London Stone: of Reasonings”.

Green Reasonings

It is also this underlying sense of self-contempt, and the concomitant diminishing of human life, that can sadly be heard within so many contemporary environmental movements. Perhaps the co-founder of the World Wildlife Fund summed up this implicit approach best, when he commented: “In the event that I am reincarnated, I would like to return as a deadly virus, in order to contribute something to solve overpopulation” (cited in the Guardian). The co-founder of the WWF was of course Prince Philip; he co-founded it with former Nazi SS Officer Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, who was closely affiliated with the Eugenics movement (as was Sir Julian Huxley, another co-founder) and also one of the founders of the Bilderberg international power group.

It is also this underlying sense of self-contempt, and the concomitant diminishing of human life, that can sadly be heard within so many contemporary environmental movements. Perhaps the co-founder of the World Wildlife Fund summed up this implicit approach best, when he commented: “In the event that I am reincarnated, I would like to return as a deadly virus, in order to contribute something to solve overpopulation” (cited in the Guardian). The co-founder of the WWF was of course Prince Philip; he co-founded it with former Nazi SS Officer Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, who was closely affiliated with the Eugenics movement (as was Sir Julian Huxley, another co-founder) and also one of the founders of the Bilderberg international power group.

This vein of anti-human ideology within a movement purportedly there to deify and enhance “Nature” would be no surprise to Blake, who as we have seen decoded the basic position behind the post-Enlightenment endorsement of naturalism and materialism as a profoundly pitiful and cynical indifference to human life, and a further example of adherence to “The God of This World, & the Goddess Nature/Mystery Babylon the Great, The Druid Dragon & Hidden Harlot” (Jerusalem 93: 23-24).

the self-hatred that is polluting the environmental movement

Albion starts to awaken when he finally realises his own complicity in these movements, these deep psychological processes. Blake not only reveals the political and spiritual ramifications of “Nature”/“Babylon” worship and deftly unpacks the materialistic and consumerist ideology contained within it, but he also accurately and acutely diagnoses the Freudian basis of post-industrial Nature worship, as an unconscious and delusional form of “Mother worship”: “Worshipping the Maternal/Humanity, calling it Nature, and Natural Religion’” (Jerusalem 90: 65-66; see also psychotherapist Andrew Samuel’s penetrating discussion of the “self-disgust”, “misanthropy”, and “idealisation of nature” that is unfortunately, and counter-productively, evident in “much of the new environmental politics”, in ‘Against nature’, The Political Psyche).

In fact it is Albion’s “wife”, Brittannia, who awakens first (“England, who is Brittannia”), recognising her own part in these self-dividing histories, and lamenting that she has murdered Albion: “In Stone-henge & on London Stone & in the Oak Groves of Malden/I have Slain him in my Sleep with the Knife of the Druid” (Jerusalem 94:24-25). Albion’s immediate response, on awakening, is anger – “Albion rose in anger” – in fury and indignation at the desiccation of his kingdom that these processes and belief-systems have inaugurated and perpetuated, and at what they’d done to his country. And more especially, what they’ve done to the “Divine Vision”, slaughtered through the programs of natural perception and the mills of rational thinking, and still unable to know how to prevent these egoic patterns of thought from recurring:

I behold the Visions of my deadly Sleep of Six Thousand Years

Dazling around thy Skirts like a Serpent of precious stones & gold

I know it is my Self (Jerusalem 96: 11-13)

But this merely shows how much “Albion”, “the Universal Humanity”, has in fact awakened and “seen”: that the central threat comes from his own Selfhood (which Blake identifies here with the “Covering Cherub” described in the Book of Genesis). This “my Self” is the sleep of six thousand years. On uncovering or realising the true nature and function of egoic thought (“ἀποκάλυψις”), the real divinity in the universe then arises within Albion, whom Blake variously terms “Jesus”, the “Universal Humanity”, “the Human Imagination”, “The Divine Body”, “the True Vine of Eternity”.

Awakening

As Damon notes, “this Eternity which the poet perceives is the human signification, for Nature is only a projection of ourselves” – “the visible portion of Soul”, and “an externalising visualising of the Individual’s emotions”. This is not to deny the reality of the sensory world, but to enhance it: in Blake’s super-charged and revitalised vision, the whole world burns with life and spirit.

What it will be Questiond When the Sun rises do you not see a round Disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea O no no I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying Holy Holy Holy is the Lord God Almighty I question not my Corporeal or Vegetative Eye any more than I would Question a Window concerning a Sight I look thro it & not with it. (A Vision of the Last Judgment)

It stops being the world of ‘things’ – the illusion of discrete objects separated in space, literalised and naturalised out of existence and out of relationship with humanity – and starts becoming psycho-energised and expansive. The material world is restored to its true meaning of being the “material” for Imagination to create and recreate, its previous representational aspect burned up: once man regains his senses “the whole creation will be consumed and appear infinite and holy whereas it now appears finite & corrupt. This will come to pass by an improvement of sensual enjoyment” (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell).

“To accept this world of matter as real is ‘atheism’ ” for Blake because it denies us access to this uncovering of reality, and keeps us locked up within the ratios of what can be made explicit, pointed to, and measured. “For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narow chinks of his cavern.” ‘Nature’ is the finite, fictional representational matrix world of the left hemisphere, Urizen’s shadow, and the dream of Ulro.

Fourfold Vision: “To see expansively is to see with the whole brain”

To see expansively is to see with the whole brain – with all of our physiological and spiritual operating systems integrated, and working in tandem – the intellectual, emotional, physical, and spiritual – a “Fourfold Vision” as Blake calls it, not just the view of the world with one or two of these flickering on and off. When man sees the world through the eyes of the Imagination, with the eyes of the “right hemisphere”, its underlying reality is revealed – as human. “Man looks out in tree & herb & fish & bird & beast/Collecting up the scatter’d portions of his immortal body/Into the Elemental forms of every thing that grows” (FZ viii: 561). And in the final reunion of God and Man, “All Human Forms [are] identified, even Tree, Metal, Earth & Stone: All Human Forms identified, living going forth & returning wearied/Into the Planetary lives of Years, Months, Days & Hours reposing/And then Awaking into his Bosom in the Life of Immortality” (Jerusalem 99:1).

Rod Tweedy is the author of The God of the Left Hemisphere: Blake, Bolte Taylor and the Myth of Creation, a study of Blake’s work in the light of modern neuroscience, and has also written a number of articles and reviews on Romanticism and popular culture, including Iain McGilchrist, Ang Lee and the Revolution of Perception, Frozen Children: The pathology of contemporary Disney, How We See War, and David Bowie: Alienation and Stardom. He is a former trustee of the William Blake Society and an enthusiastic supporter of Veterans for Peace UK and the user-led mental health organization, Mental Fight Club.

I am also fascinated by Blake and agree that he is centuries before his time. I especially identify with his personification of the rational mind as Urizen and agree that the key to his system is his Fourfold Vision. I am interested in correspondences between his system and Buddhist thought. It is actually a misconception that Buddhism regards life as ‘illusion.’ (in a philosophical sense). The ‘cleansing of the doors of perception’ could be equated with cleansing karma which is done through meditation and mindfulness whereby the meditator no longer acts from the three poisons of hatred, greed and delusion. Any comments wd be welcome!

Does your critique mean we have to jettison the scientific view of the universe? Surely not – we shd just acknowledge it as co-existing with the spiritual or imaginative view.

LikeLike

Yes – it’d be terrific to find something on the correspondences between Blake and Buddhist thought. The Blake Society held a meeting in 2015 with the Buddhist poet Maitreyabandhu, which shed some light on this, and we were hoping to include some posts with a Trustee of the Society last year about exactly this – he believes that there’s a ‘left brain’ or abstracting version of Buddhism (i.e. based on the left hemispheric concepts of ‘light’, ‘purity’, ‘holiness’ – everything that Blake associates with Urizen) and a whole brain/right brain version, which as you say is focussed on the idea of the Now, of Being, and the divinity of the body and the need to let go of Selfhood. If you come across anything on this – or would like to write something yourself – please let me know! With regard to your second query, I think both Blake and McGilchrist are passionate defenders of the ‘scientific view’ – at the end of the Four Zoas Blake notes that “sweet Science reigns”. The problems come I think when science doesn’t see that it’s only one tool in the toolbox – only one way of perceiving and understanding reality – that it’s a wonderful Emissary but a very poor Master, in McGilchrist’s terms. I think Rupert Sheldrake is making very interesting inroads into what a genuinely imaginative scientific framework – that is, a genuinely scientific framework – might be like., e.g. here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JKHUaNAxsTg

LikeLike

I’m not sure if I mentioned I’m writing a book interpreting Blake’s Book of Job with the Dark Night of the Soul – personal transformation from a Buddhist perspective? I

LikeLike

Sounds good. If you’d like to post an excerpt from it here as a trailer for the book just let me know – thehumandivine@hotmail.com

LikeLike

I could post an extract along with an engraving if you think readers wd be interested.

LikeLike

Hi – yes that’d be great. Please just send the extract and engraving (to: thehumandivine@hotmail.com) and then we can make an initial post of it to you to check and approve. If you need any more info etc just let me know – Rod

LikeLike

Cool article. I’m glad to have made its discovery. https://archive.org/stream/workesofmosthigh00jame?ref=ol#page/n8/mode/2up

LikeLike